- Interviews

Docs: “Filmmakers for the Prosecution” – How Films Made their Case at the Nuremberg Trials

It was 1945 and as the war in Europe wound down, Stuart and Budd Schulberg, two young US officers, rushed around Germany in a race against time. The two brothers – Budd, 31, a navy lieutenant and Stuart, a 23-year-old marine corps officer – had been dispatched by the OSS on a special film-finding mission.

The Army’s Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was the military’s intelligence agency, and it included a motion picture/propaganda division, famously headed by Oscar-winning and Golden Globe-nominated director John Ford. Ford recruited Hollywood professionals for the camera crews which filmed and documented US soldiers in action in Europe and the Pacific throughout the war and also made training films for OSS spies. The Schulberg brothers were among Ford’s men, and now they had been tasked with their biggest mission: find, salvage and assemble war footage that could be used as evidence of Nazi war crimes for the upcoming Nuremberg trials.

The legal proceedings that took place in that German city were a joint effort by the Allies to hold Nazi leaders accountable and put their crimes against humanity on the historical record, in the hopes that they would never be repeated.

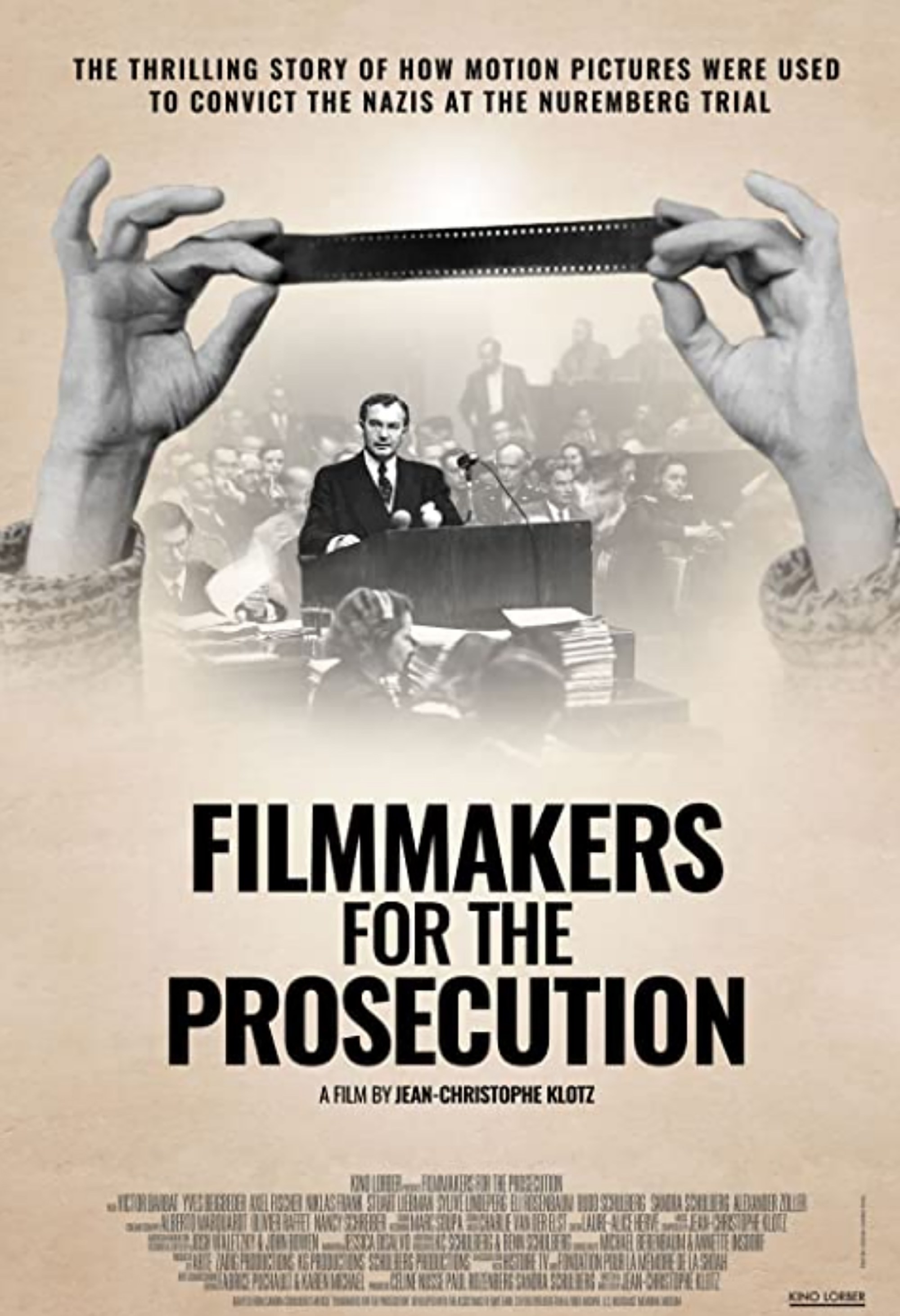

This is the story told in Filmmakers for the Prosecution, the fascinating documentary directed by Jean-Christoph Klotz and produced by Sandra Schulberg. Schulberg is an old acquaintance of the HFPA which has supported the restoration efforts of IndieCollect, the company she founded to preserve independent cinema. She also happens to be the daughter of Stuart Schulberg, that 23-year-old soldier who, in a still-smoldering Germany, was about to step into history. Produced by ARTE and broadcast by the arts and culture channel in Germany and France last year, the documentary recently had a limited theatrical run in Los Angeles and New York ahead of a DVD/streaming release schedule being readied by distributor Kino Lorber.

The film begins as a thriller. After German capitulation in May 1945, the trial date for captured Nazi leaders had been set for September of 1945. That left only a few months to ready the case for the prosecution, which rested in part on presenting documentary film evidence of Hitler’s totalitarian rise, the Nazi’s imperialistic wars of aggression and their “final solution.”

The decision was made that the most effective “testimony” would be from films that the Germans themselves shot. The Nazis scrupulously documented their actions, especially their rallies and military efforts, for propaganda purposes. Now, with the country in ruins, the clock was ticking to find the film in time for the trial. The Schulbergs rushed from town to town following leads to warehouses and depots – even an abandoned salt mine – where films had been stored. Often, they arrived too late, sometimes just days after the canisters had been set afire to destroy the evidence. Their work was complicated by the division of occupied Germany into sectors controlled by different allies.

In the end, they would locate hundreds of hours of film, sifting through them (sometimes with the help of filmmakers like Leni Riefenstahl) as they assembled the damning material that would be projected onto a special screen set up in the Nuremberg courtroom – the first time moving images would be used in this way. Watching the documentary, one can hardly avoid noting the parallel with the 2022 congressional hearings of the January 6 commission whose public investigation made similar use of the videos shot during the Capitol Hill insurrection.

The OSS film unit was originally tasked with filming the trial itself but at the last minute that job was assigned to the US Signal Corps. In fact, this was arguably an even more important mission as it would produce a film that would disclose to the world the crimes committed and how justice was done. (The trial would be fictionalized in Stanley Kramer’s Judgement at Nuremberg (1961) which received six Golden Globe nominations and produced a Best Director win for Kramer and a Best Actor Globe for Maximilian Schell.) Apart from aiding the process of German de-Nazification, the documentary on the trial was meant to divulge Nazi horrors to the citizens of the world, lest they ever be repeated.

When Budd Schulberg left to pursue his writing career (he would go on to win an Academy Award for the screenplay of On The Waterfront in 1957), younger brother Stuart, barely 25, was left to direct what would become Nuremberg: Its Lesson for Today (1948). The film was the first of hundreds of subsequent works dealing with the Holocaust, foundational to the role of film in perpetuating the memory necessary to avoid repeating the tragedies of history.

(The subsequent Nuremberg trials – the trials of Nazi judges – would be fictionalized in Stanley Kramer’s Judgment at Nuremberg (1961), which received six Golden Globe Nominations and produced a Best Director win for Kramer and a Best Actor Globe for Maximilian Schell.)

In this respect, the story is all too relevant to the current debate on historical memory and the struggle to control the narratives of the past. As it happens, Nuremberg: Its Lesson for Today was distributed in Germany – but not in the United States or elsewhere. By 1948, the political climate had shifted toward the East-West tension that would dominate the next five decades of the Cold War. The United States was no longer as interested in denouncing the crimes of Germany (a newfound ally against the USSR.) Nor was it convenient to the Cold War mythos to evoke a trial in which the US and the USSR had closely collaborated. So the film was shelved, never shown in American theaters until it was recently restored and re-released through the efforts of Sandra Schulberg.

It is a poignant footnote to Filmmakers for the Prosecution, one that speaks to current efforts to control the present by manipulating historical memory and perhaps the fundamental, enduring tension between truth and power.

We spoke to Sandra Schulberg after the recent Los Angeles premiere.

It must have been a very personal project for you, producing this film, it includes never before seen footage of your father working back then, editing film…

When they found that footage, they sent it to me because they needed confirmation that was indeed my father. And, of course, I recognized him. Jean-Cristoff was just looking for B-roll of people editing, those had been the search terms submitted, and that footage came up – and they just could not believe that it was actually Stuart Schulberg – totally by chance.

One of the most amazing events in the documentary tells of how they were able to find a process stash of films at Berlin’s Babelsberg studios – in the Soviet sector…

[My uncle] Budd was based outside of Berlin, and he would talk to the prosecutors to ask which specific shot would be useful in the prosecution. He got wind that there were many films stored at the old Berlin film studios. So they went there and they met the Russian officer in charge who was flummoxed that this young naval officer was showing up, doing what? But the minute they mentioned that they worked for John Ford, he could not believe it. “John Ford? You know John Ford??” And it turned out that this officer happened to be one of the foremost Soviet scholars on Ford and knew his work in detail. And he was so captivated that Ford was in charge of this unit that he said: “take anything you want.”

Ford was an old acquaintance of the Schulbergs, right?

John Ford watched my father and uncle grow up in Hollywood. I think that was in part the reason they were assigned to his OSS unit because they knew each other. I have a photo of Ford attending my parents’ tiny wedding ceremony held in 1944 in my grandparents’ apartment in NYC. My grandfather was BP Schulberg who was head of production for Paramount on the West Coast. Zukor owned Paramount but he sent BP out to Hollywood to run the studio in 1927. So BP was one of the early Hollywood moguls, as powerful as those early figures.

One of the incredible things about your documentary is how it foreshadows so many issues of great relevance today. Beginning with the use of filmed images in the pursuit of justice.

Yes. We all know that the January 6 commission made extraordinary use of video to lay the groundwork for their investigation. I think we’ll find the same thing in Ukraine. One of the people who appear interviewed in our film – Eli Rosenbaum – has recently been appointed to the new office of Counsel for War Crimes Accountability – to join a team of international prosecutors to investigate crimes of war in Ukraine. There’s an extraordinary amount of footage being shot for that purpose and assembled and sifted through as we speak.

It is sad that back then there was real hope of ending all future wars and here we are with another conflict on some of the same killing fields, with the potential to escalate to a World War. And the triumph of truth over national interest also did not come to pass quite as envisioned by the Nuremberg prosecutors.

Yes, even my father would become a victim of politics with the suppression of his documentary in the US.

Not to mention that barely a decade later, McCarthyism would bring the US to a place of ideological persecution very different from the country’s role of liberator in 1945.

My uncle Budd had himself been a very staunch communist in the 1930s, one of the organizers of the WGA and a member of the antifascist movement in Hollywood. Then he was subject to pressures by the party to censor his novel “What Makes Sammy Run,” and he would turn against the party and eventually was expelled from it. He also had writer friends in Russia who were being persecuted there, so even though he remained part of the Left, he became an anti-communist. And that is very much a part of my family’s story and it has taught me that all movements, even those who begin quite idealistically, can sometimes eat their own and you can never park your brain at the door whether it’s that of a church, or a union hall or a rally. You have to be able to make these distinctions.

And yet your father’s film was ultimately instrumental in Germany’s processing of the sins of Nazism.

Yes, and Germany has arguably attempted to teach and learn the lessons of Nuremberg better than any country – including our own. In some ways, they are way ahead of many other countries and are a pacifist nation as a result of all of this, so there were good things that came of the “de-Nazification” and re-education campaign.