- Golden Globe Awards

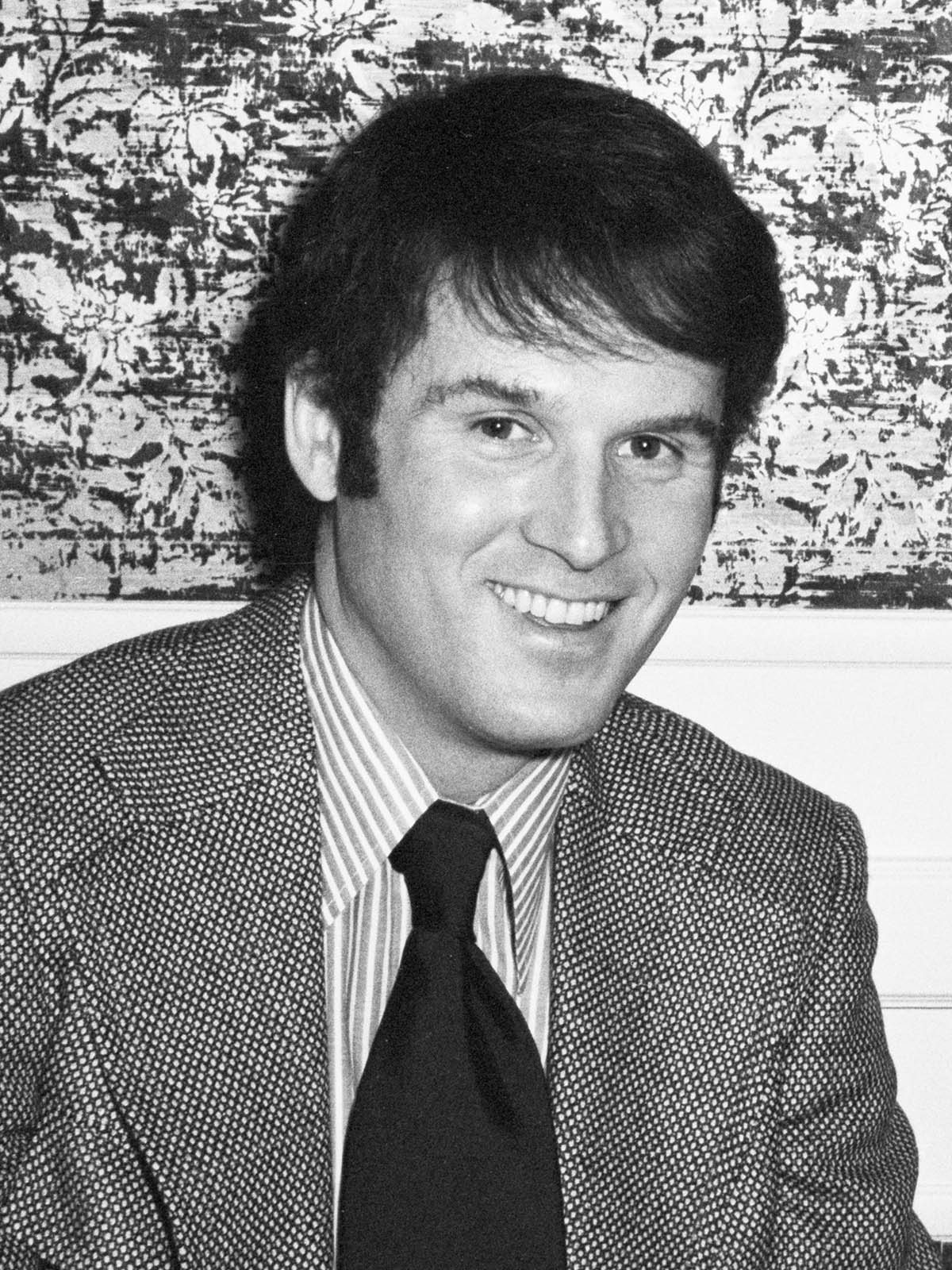

Charles Grodin: Brilliant “Everyday” Comedian Dies at 86

In a career spanning over six decades, Charles Grodin, who died May 18 at the age of 86, left his mark on every form of entertainment: stage, television, film, even late-night shows.

Though best known as an offbeat character actor in major comedies of the 1970s and 1980s, he was capable of navigating smoothly from lead to secondary roles, establishing a comedy style that was droll, offbeat, and awkward.

Born as Charles Grodinsky in Pittsburgh in 1935, he was the son of a Jewish wholesale dry goods seller. He studied at the University of Miami and the Pittsburgh Playhouse. Like other beginners, he made ends meet in New York, working nights as a cab drive and postal clerk while studying acting during the day.

In 1966, he made his debut in a low-budget comedy, Sex and the College Girl, which was a flop. Grodin then had a small role in Rosemary’s Baby and was part of the ensemble of Mike Nichols’ adaptation of Catch-22.

In 1969, Grodin showed his interest in politics by contributing to the writing and directing of Songs of America, a TV special starring Simon and Garfunkel that included civil rights and antiwar messages; unfortunately, the original sponsor pulled out. Simon returned with a special in 1977 that spoofed showbusiness and featured Grodin as the show’s bumbling producer, earning Grodin an Emmy Award.

Grodin’s big breakthrough came in 1972, when he was cast in the comedy, The Heartbreak Kid, playing a caddish Jewish newlywed who abandons his neurotic bride (Jeanie Berlin) to pursue a beautiful blonde played by Cybill Shepherd. Grodin realized he was playing a despicable guy, but he treated him with full sincerity and authenticity,” based on his belief that “My job isn’t to judge it.”

He always credited its writer-director, Elaine May, for entrusting him with a major role – “If it wasn’t for Elaine, I probably would never have had that career.” The movie was a hit and Grodin received high praise, earning a Golden Globe nomination for Best Actor in a comedy.

His biggest stage success was Same Time, Next Year, which opened on Broadway in 1975 and ran for over three years. Grodin and Ellen Burstyn played a couple who, though each happily married, meet in the same hotel once a year for an extramarital fling. Through their affair, the play reflected the changes in their personal lives (one year she appears pregnant), and in the mores of American society, from the 1950s to the 1970s.

When the play was made into a movie, in 1978, Burstyn reprised her Tony Award winning role, and the producers opted for a bigger marquee name, Alan Alda, but he was not bitter about it; that movie was a critical and commercial flop.

Grodin believed that a comedian function is to make the audience laugh, but also feel uncomfortable. When he became a familiar face on late-night TV, he would confront Johnny Carson and other hosts with a fake aggressiveness that made audiences cringe and laugh at the same time. In his many late-night appearances, he once brought a lawyer with him to threaten David Letterman for defamation. Hosting Saturday Night Live, he pretended to not understand live TV, ruining all the sketches

A string of secondary role in major comedies of the 1970s and 1980s reaffirmed his status as an actor with a wide range, who could do everything and anything. In his screen image, not unlike that of Woody Allen (who is exactly his age) he perfected a persona defined by male insecurity, likable ineptitude, and awkward delivery of lines, which was deliberately meant to get viewers out of their comfort zone.

In the next few years, Grodin played in the1976 film remake of King Kong as the greedy showman who brings the big ape to New York. He was Warren Beatty’s devious lawyer in Heaven Can Wait, Gene Wilder’s friend in The Woman in Red, Steve Martin’s co-star in 1984s The Lonely Guy.

His turn in 1981s The Great Muppet Caper was typically dedicated as a thief wooing Miss Piggy. He also took pride in appearing in May’s 1987 adventure comedy Ishtar, a notorious flop.

Many viewers remember his iconic role in the 1988 comic thriller Midnight Run, a quintessential buddy-buddy movie, opposite heavy weigh actor Robert De Niro. Grodin played an accountant who stole millions from a mobster and De Niro was the bounty hunter trying to bring him cross-country to Los Angeles. Chased by police, bounty hunter, and the Mob, the duo is forced to go by car and bus, due to Grodin’s fear of flying.

Grodin improvised many scenes, later claiming that was trying to amuse himself and his Method acting partner. “I moved a little more toward drama and he moved a little toward comedy, causing us to meet on a very good ground.” De Niro later said that he was challenged by Grodin’s style, which kept him on edge, because every take was different and he never knew what to expect.

No role was beneath him, even when he was established. In 1992, Beethoven, in which he was cast as the bedeviled father, brought him success in the family-animal comedy genre. “I am just happy to be working,” he said when asked why he agreed to play such a small and broad part.

In the 1990s, Grodin made his mark as a liberal commentator on radio and TV. He also wrote several books, defined by humor and brutal honesty about his ups and downs in the volatile and unpredictable show business

After 1994s My Summer Story, Grodin abandoned acting. From 1995 to 1998, he hosted a talk show on CNBC cable network. He moved to MSNBC and then to CBS’ “60 Minutes II.”

He returned to the big screen in 2006 as Zach Braff’s know-it-all father-in-law in The Ex. Other recent credits include the films An Imperfect Murder, the TV series Louie, and Noah Baumbach’s 2014 While We’re Young.

Aware that he lacked the usual Hollywood good looks of a leading man, he succeeded in building an ordinary persona, “the Everyday Comedian,” a type that many viewers could relate to.

Grodin could steal entire scenes with just a simple look, understated delivery, and deadpan style. His commitment, whether acting opposite De Niro or Miss Piggy, was unsurpassed. Modest to a fault, he embraced all his roles with equal attention and aplomb, claiming “I’m not that much in demand, it’s not like I have many wonderful offers. I’m just delighted that they still want me, so I try to do my best.”

He characteristically observed in his first book, It Would Be So Nice If You Weren’t Here: “I didn’t suffer from the frustration of all the rejections. They just gave me more time to think and to train.”