- Golden Globe Awards

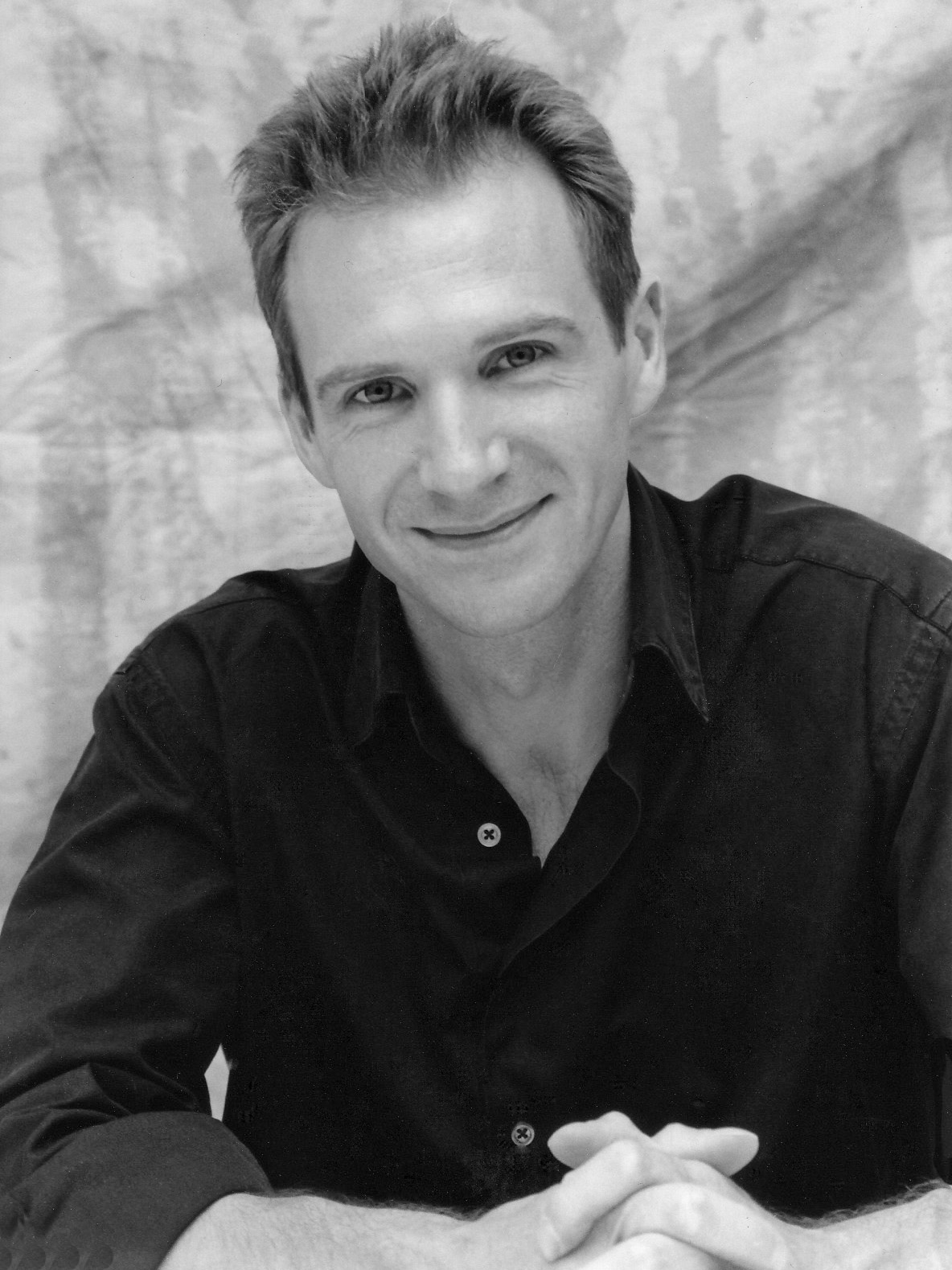

Ralph Fiennes, 2005, on “The Constant Gardener” – Out of the Archives

In 2005 Ralph Fiennes spoke to journalists of the Hollywood Foreign Press about The Constant Gardener, directed by Fernando Meirelles from the 2001 novel by John le Carré, where he played a British diplomat in Kenya trying to solve the murder of his wife Tessa (Rachel Weisz), an Amnesty activist. He addressed the corruption of big pharmaceutical companies and supporting UNICEF, issues still timely today.

The British actor had seen a documentary about a real-life case in Kano, Nigeria, where the drug manufacturer Pfizer administered the new antibiotic Trovan to children during a 1996 meningitis epidemic without their parents’ consent: “I have a bit of knowledge about the pharmaceutical issue, not anything as extreme and as shadowy as the story of the film, but I did know that there’s a big debate about access of drugs in third world countries, particularly drugs related to HIV. I’m not a spokesman on big pharma or government, but I knew that it was an issue. We were all given this documentary on a particular case, where a big pharma company had tested an unsound drug on unsuspecting people. So there is a genuine, real background story to this film, which I was aware of when I started making it.”

The filmmakers were allowed to shoot in Kenya, despite the fact that the story of The Constant Gardener was critical of the government: “When the book was written there was a strong reaction, because it was clear that John le Carré was quite critical of the regime under President Daniel Moi, which is known for its terrible corruption. When the book came out, Moi was still in power, so you couldn’t buy it in Kenya, you had to get it under the counter. But there’s been a regime change since then. Also, our film script didn’t focus on any criticism of a particular regime, so that wasn’t really a problem. Actually, the villain in our movie is more the British government alongside the big pharma companies, so the Kenyan government was keen to host our film, and we were helped a lot by the British High Commissioner in Kenya, Edward Clay, he was extremely helpful in making it possible.”

Back in 2005 there was a timeliness to this story – as there is today, during the COVID-19 worldwide pandemic – when African nations have had reduced access to vaccines: “There has been a great media focus on Africa in the news recently, so it’s perhaps serendipity that the film is coming out when there has been such enormous concentration on Africa, particularly relating to poverty and disease. One of the things that I discovered was that many western countries have actually been pouring a lot of money into Africa over a number of years. But it’s important that Africa, and any third world country, has a high profile all the time, that good publications and television programs do focus in on problems, whether it’s in India or South America or Africa. Also, when we say Africa, it’s like saying Europe, because Africa has got many different countries, many different climates, many different kinds of terrain and different degrees of development.”

It was eye-opening and emotional for the actor to shoot in the Nairobi slums of Kibera, where everyday life was far removed from our western lifestyle: “The visitor in the African countries is hit by a number of different sensations, and especially if you know you’re going to somewhere like Kibera, you steel yourself to be appalled. You can be shocked and upset by the lack of sanitation, as you have to walk across open sewers full of human waste. It is shocking, but, at exactly the same time, you encounter extraordinary vitality and warmth and openness, particularly transparent in children. So that affects you and it moves you. It’s curious because I had almost at the same time sensations of being depressed and upset, but also of being uplifted.”

Fiennes had similar experiences when he visited Uganda as a spokesman for UNICEF, the United Nations Children’s Emergency Fund: “The two trips that I’ve done with that organization, one to Uganda and one to Kyrgyzstan, were great eye openers for me about the huge problems that people face, whether it’s through disease or displacement from their home, sheer poverty, lack of educational facilities, lack of any certainty in their lives. And it’s humbling, because people who in many situations have nothing, also have a kind of dignity, courage and spirit, that maybe people who have too much don’t have. When I go on a trip with UNICEF, and I meet children in orphanages and places like that, I’m very affected. The personal interaction with someone is what will affect you more, then you can see the palpable reality of what needs to be done. It’s hard to keep countries like Kenya, Ethiopia or Sudan intelligently in focus for people, to give the public the information, because they can easily feel bombarded. But we have to do that, so a film like The Constant Gardener can make a difference, provoke discussion about corruption in big pharma companies and the government’s relationship to the transparency that a big corporation should have publicly. Outright, blatant corruption, that’s really a case for the law, and people should get angry about it.”

The actor replied to a question about the symbolical meaning of the title The Constant Gardener: “My feeling is that John le Carré wanted to show someone who might apparently be very unheroic, not the obvious material for a hero, becoming quietly strong. For me that has a correlation with the kind of patience that’s needed to nurture a plant into growth and bloom. My father was a brilliant gardener, so I’ve always thought that the good gardener has to be present and watchful, alert and tender. I find it a very moving idea that Justin Quayle never essentially changes his gentle nature; he becomes tough towards the end, insistent and quite passionate, but he never betrays his spirit. I feel that the metaphor of the gardener is about being always present with loyalty, determination and love.”