- Cecil B. DeMille

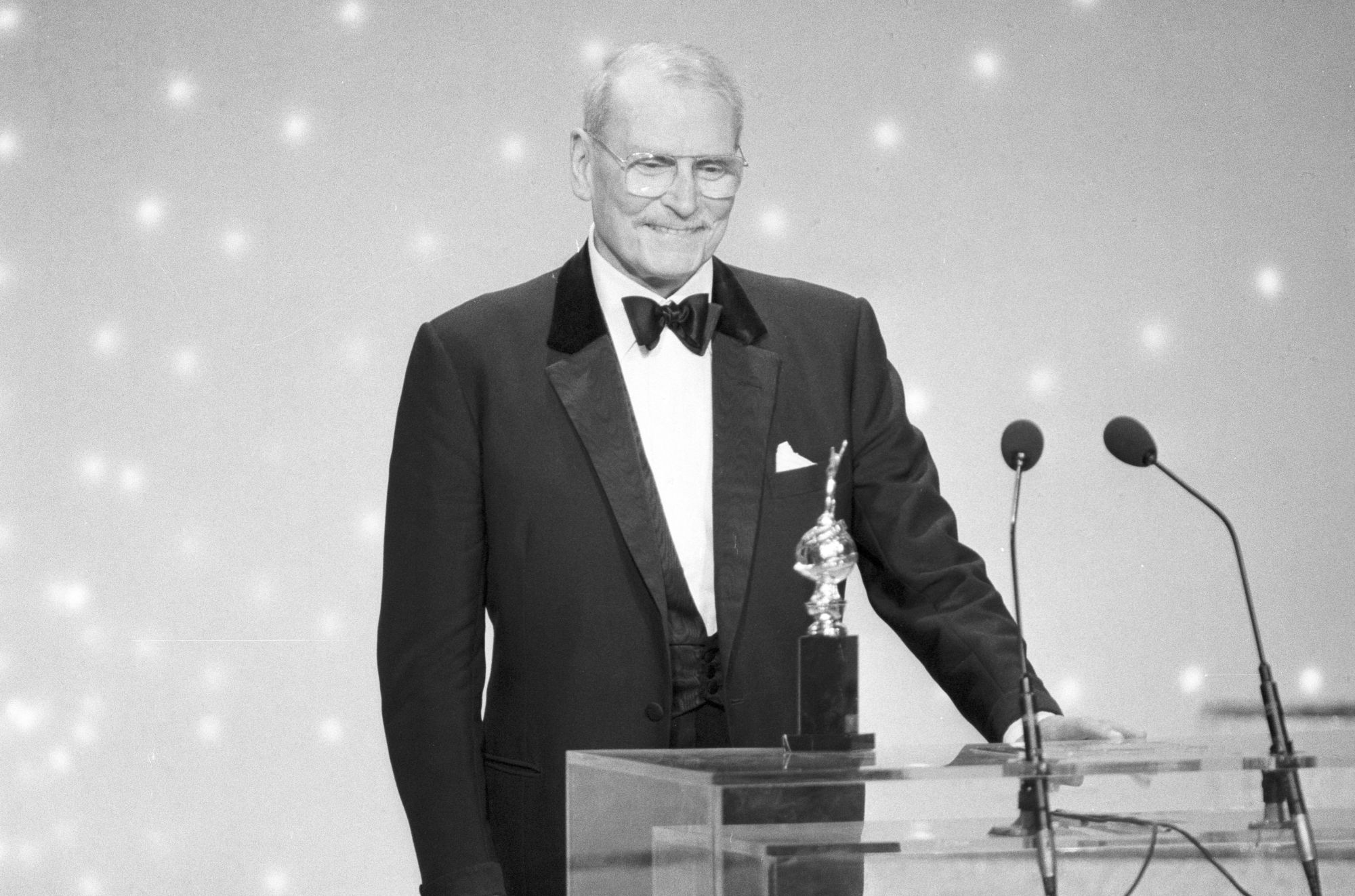

Ready for My deMille: Profiles in Excellence- Laurence Olivier, 1983

Beginning in 1952 when the Cecil B. deMille Award was presented to its namesake visionary director, the Hollywood Foreign Press Association has awarded its most prestigious prize 66 times. From Walt Disney to Bette Davis, Elizabeth Taylor to Steven Spielberg and 62 others, the deMille has gone to luminaries – actors, directors, producers – who have left an indelible mark on Hollywood. Sometimes mistaken with a career achievement award, per HFPA statute, the deMille is more precisely bestowed for “outstanding contributions to the world of entertainment”. In this series, HFPA cognoscente and former president Philip Berk profiles deMille laureates through the years.

No Cecil B. deMille recipient has, by some measure, diminished in stature as much as Laurence Olivier. Once considered the greatest actor of his time he hardly merits a mention these days. You have to wonder why.

Bogart had a lisp. Olivier’s voice was impeccable. But which of the two is the greater star?

Of course, Bogart had the dubious advantage of dying young. Olivier lived to a ripe old age. And, more concerned about supporting his young family than his legacy, he accepted whatever parts he was offered.

He will, however, always be known for popularizing Shakespeare for the masses.

Already a star in the theater before he was 30, both in the West End and on Broadway, he seemed ideally suited to movie stardom, but after Hollywood misfires at MGM and RKO and at Alexander Korda’s London Films, it was Samuel Goldwyn who rescued him.

Cast as Heathcliff in William Wyler’s film of Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights, he became a worldwide sensation, and then when Selznick cast him as Maxim de Winter in Hitchcock’s Rebecca his future as a Hollywood heartthrob was secure.

He credited Wyler with ridding him of his English stuffiness and making him a movie star, which he did by demanding take after take for every shot on Wuthering Heights. Olivier always acknowledged that debt.

While shooting that film in Hollywood, he was having a much-publicized affair with Vivien Leigh, who overnight had become the world’s most sought after actress. Playing Scarlet O’Hara in the Gone With the Wind not only won her the Oscar but made them the most famous couple in the world. Their cohabiting caused a scandal; they were both married to others but in unhappy relationships. (Three years later, after securing divorce petitions they married in Santa Barbara.)

But at that moment the world was their oyster — until Hitler intervened. Both of them patriotically returned to England to help with the war effort. Leigh had to wait ten years to regain her former stature when in 1952 she won her second Oscar for playing Blanche du Bois in A Streetcar Named Desire, but for Olivier, the war years and post-war period was his greatest decade.

While still under contract to Alexander Korda he made patriotic films at Winston Churchill’s behest. Churchill believed his and Leigh’s 1941 Hollywood collaboration That Hamilton Woman (Lady Hamilton) did more to aid the war effort than any propaganda film of that period, and he rewarded Korda with a knighthood.

Olivier made only one notable (anti-Nazi) film at the time, Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s 49th Parallel, but he was convinced the ultimate jingoistic film would be Shakespeare’s Henry V. Against strong opposition he was able to secure financing to make what few thought would be a box office success.

How wrong they were!

The film became an international hit, nominated for four Oscars, including best picture and best actor. Olivier won a special Oscar for bringing Shakespeare to the screen, and the film also won many honors from American critics including numerous best director awards.

Suddenly Olivier was the wonder of the Western world, and he followed that achievement with his greatest film Hamlet, which he produced, directed, and starred in, playing a blonde Hamlet, for which he won both the Golden Globe and the Oscar. The film itself won four Oscars including best picture and the Best Foreign Film Golden Globe. Thanks to Olivier’s direction, the film had a dynamic that has never been equaled in any Shakespeare film adaption since, though many were critical of the liberties he took with Shakespeare’s play. (No Rosencrantz and Guildenstern.)

No matter, Olivier was now the screen’s most sought-after talent, and everyone wanted him. Of course Hollywood beckoned, and logically he went with William Wyler’s Carrie, in which he gave one of his greatest performances as George Hurstwood, in the screen adaptation of Dreiser’s novel Sister Carrie. But even though his costar was the top actress of the decade, Jennifer Jones, in one of her best performances, the film was a commercial failure, and Olivier returned to England, where he soon became the greatest theatre actor-manager of his time.

He took time out to direct and star in his third Shakespeare venture, Richard III, which won the Best Foreign Film Golden Globe and had the distinction when it was broadcast on NBC of commanding a larger audience than had watched all Shakespeare plays in history.

So now, who wanted a piece of this man? None other than the biggest Hollywood star of the 50s, Marilyn Monroe. She thought he would jump at the chance of their making a movie of the Terrence Rattigan play The Sleeping Prince, which he had once done on the West End with Vivien Leigh.

And jump he did, but much to his regret. Marilyn proved so difficult to work with, he reportedly wanted to strangle her. Looking at the film today, however, it’s possibly their best screen performances, certainly hers. That experience certainly aged him, and thereafter he played mature characters usually supporting roles in prestigious Hollywood films such as Marathon Man, Bunny Lake Is Missing, Spartacus, Khartoum, The Shoes of the Fishermen, Nicholas, and Alexandra, The Seven Percent Solution, A Bridge Too Far, and The Betsy, for which he was always paid top dollar for all of them.

His film acting career was not over, however. In between he triumphed twice, once playing Archie Rice in The Entertainer a role he created on stage when he ran the National Theatre in London with Kenneth Tynan, and a second time winning the NY Film Critics award as best actor for Sleuth, besting Marlon Brando’s The Godfather performance in the process.

He was unjustly blamed for Vivien Leigh’s unhappiness and subsequent death after he left her for a much younger Joan Plowright. That marriage wasn’t all roses, but they sired three children, and she stayed with him through a prolonged final illness. He was buried with full honors in Westminster Abbey after receiving every honor a country could bestow on England’s greatest actor-manager of the last century.

His legacy as a film actor is overdue for a re-evaluation.

So how many classics can Olivier claim? Certainly Hamlet and Henry V, maybe Wuthering Heights and Rebecca, although they really belong to Hitchcock and Wyler.