- Cecil B. DeMille

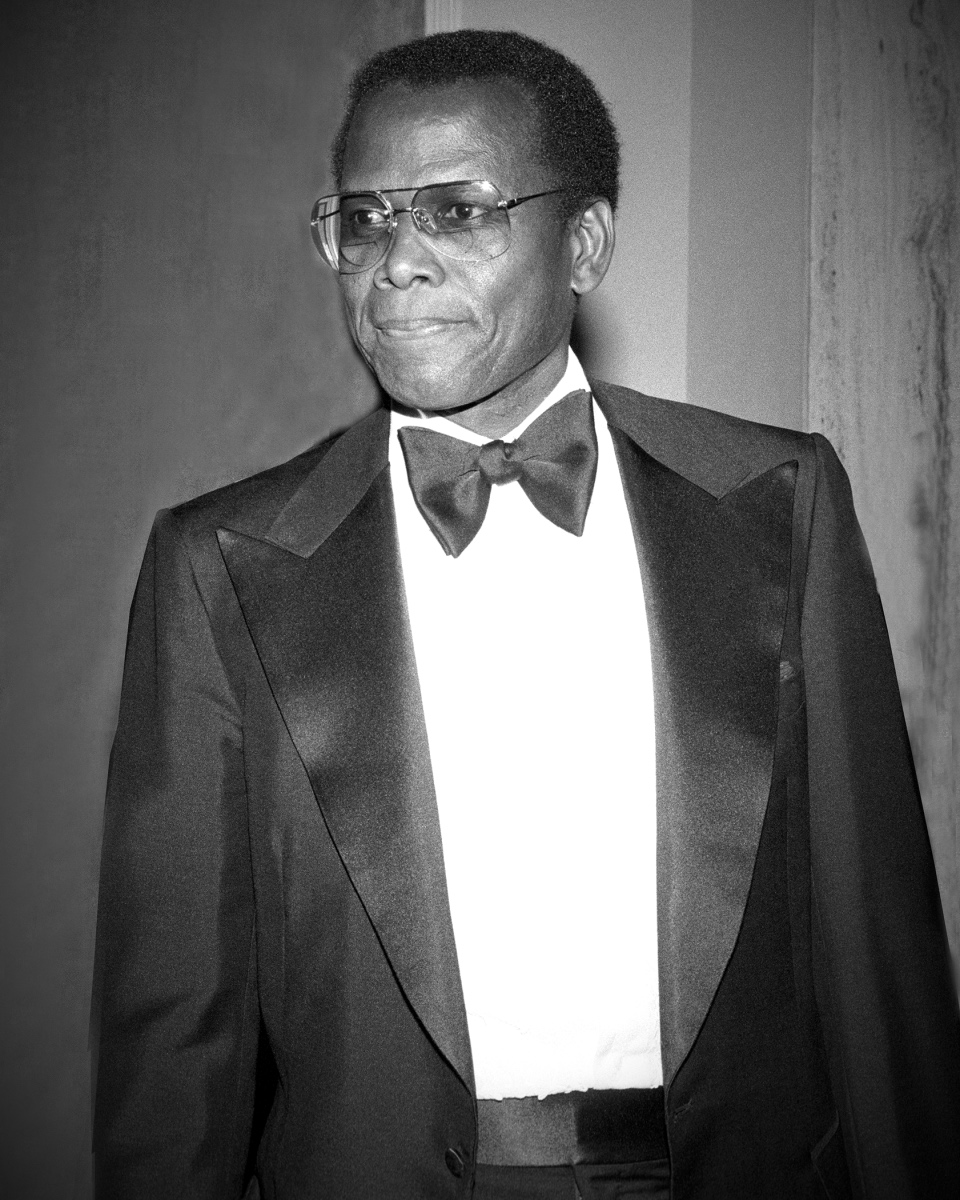

Ready for My DeMille: Profiles in Excellence – Sidney Poitier, 1982

Beginning in 1952 when the Cecil B. DeMille Award was presented to its namesake director, the Hollywood Foreign Press Association has awarded its most prestigious prize 69 times. From Walt Disney to Bette Davis, Elizabeth Taylor to Steven Spielberg and 62 others, the deMille has gone to luminaries – actors, directors, producers – who have left an indelible mark on Hollywood. Sometimes mistaken with a career achievement award, per HFPA statute, the deMille is more precisely bestowed for “outstanding contributions to the world of entertainment”.

Cecil B DeMille honoree Sidney Poitier not only broke ground for Black actors, but his early box office clout also has never been equaled by any actor of color. And he was the first African American to have a significant following with audiences internationally.

Although born in the U.S. during his family’s visit, he lived in the Bahamas until he was ten, and after deciding he wanted to be an actor he worked on losing his Bahamian accent by watching television in his adopted country. His first professional work was with the American Negro Theater, which led to a leading role in the Broadway production of an all-Black production, a revival of Anna Lucasta.

It was Darryl F. Zanuck who lured him to Hollywood, casting him in a co-starring role opposite Richard Widmark and Linda Darnell in Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s No Way Out, the first major studio movie to deal with racial bigotry. Although the film wasn’t well-received, he was quickly signed to play a key role in the film version of Alan Paton’s acclaimed novel Cry, the Beloved Country. A minor supporting role in Universal’s Red Ball Express led to an important one in legendary cinematographer James Wong Howe’s only directing effort Go Man Go and a brief role in William Wellman’s Goodbye My Lady.

Screenwriter Robert Alan Arthur finally gave him a lead in Edge of the City, and after that, he never looked back. He followed that with Richard Brooks’s hard-hitting Something of Value, in which he played a sympathetic Mau Mau adherent; then he accepted the role of a slave in Band of Angels, an unfairly maligned Clark Gable Civil War romance.

Stanley Kramer gave him the role that made him a star in 1958. Playing opposite Tony Curtis in The Defiant Ones, he earned his first of eight Golden Globe nominations. The film didn’t win the Oscars maybe because one of its writers (even though he was using a pseudonym) had been blocked. The Hollywood Foreign Press, however, gave it its Golden Globe for best motion picture drama.

Poitier was now the go-to African American actor, replacing Harry Belafonte in Samuel Goldwyn’s Golden Globe-winning Porgy and Bess, for which he earned his second Golden Globe nomination.

He played opposite Alan Ladd in the forgettable All the Young Men, sharing top billing with the star, then distinguished himself in the film version of Lorraine Hansberry’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play A Raisin in the Sun, a role which he had originated in the theatre, and for which he was nominated for his third Golden Globe.

He co-starred opposite Paul Newman in Paris Blues and finally won both the Golden Globe and Oscar, the first African American actor to do so, for his role as a handyman who builds a chapel in the desert for a group of nuns in Lilies of the Field. He played opposite Anne Bancroft in The Slender Thread, and then had his first box office hit as the love interest of a blind Caucasian girl in A Patch of Blue.

The film that made him a superstar was his next one: To Sir, With Love, which was embraced by audiences the world over. Poitier was the only recognized name involved, and it was his appeal that made it a huge hit and inspired a title song that topped the charts. Suddenly he was Hollywood’s biggest box-office star.

He was Golden Globes-nominated for In the Heat of the Night, which enabled his costar Rod Steiger to win his only Golden Globe and Oscar. He was the exemplary African American guest in Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner opposite Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn, which was embraced by audiences worldwide, making it the biggest moneymaker of the year.

After that he coasted along in For Love of Ivy and in the In the Heat of the Night’s sequel They Call Men Me Tibbs. But then joining forces with his buddies Harry Belafonte and Bill Cosby, he pioneered a series of films that were mainly geared to Black audiences, who were now growing in numbers, with Brother John, Buck and the Preacher, Uptown Saturday Night, Let’s Do It Again among them. In between, he made The Wilby Conspiracy, Shoot to Kill, and Little Nikita, but then, after accepting a secondary role in Robert Redford’s Sneakers, his brilliant acting career was nearly over.

For the past 20 years, he’s done perfunctory work in television, although he did receive a Golden Globe nomination as best supporting actor in television for Separate But Equal in 1991. During his career, he also directed nine movies, including two that starred Gene Wilder.

Whenthe Golden Globes awarded him the lifetime achievement award in 1982, he didn’t show up, one of only three recipients who passed on participating in the ceremony.