- Industry

Greek Lobster A Hit

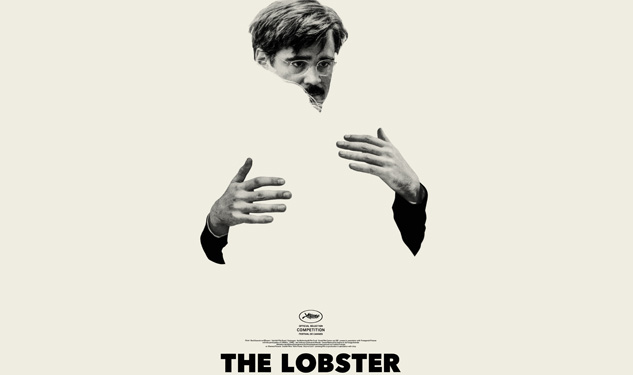

The Lobster by Greek iconoclast Yorgos Lanthimos won the Jury Prize at this year’s Cannes Film Festival. The film, which was acquired for distribution by Alchemy, marks the latest success in the director’s singular canon of the absurd. The HFPA’s Ersi Danou, co-founder of the Los Angeles Greek Film Festival looks at the phenomenon. Greek Weird Cinema – An Answer to Theo Angelopoulos’ Legacy

The 60s and 70s were years of change, and cinema reflected this. The man who alone gave Greek cinema its identity as such was undoubtedly Theo Angelopoulos. His long and slow shots, the solemn faces and landscapes, the absence of emotionalism and the focus on historical events from a political perspective created a style of visual expression that was not only revered by European critics but also coveted and imitated by a whole generation of filmmakers in Greece – a legacy that lasted at least three decades.

While Angelopoulos’ films seemed somehow genuinely conceived and their dark world appeared intact, the influence on other creators was, to say the least, restrictive. Greeks are loud, humorous, emotional, passionately engaged in politics – a true Mediterranean spirit that complies with the clichés of the South. But on screen, the Greek audience strained to recognize itself in poorly acted and self-conscious dramas. To be fair, there were brilliant exceptions. Pantelis Voulgaris, Nikos Koundouros, Kostas Ferris – to name a few – had all sporadically explored their personal way of defining cinema in contradiction to the naïve post-war black & white melodramas and comedies produced by Finos Film. And yet, Theo Angelopoulos’ legacy proved to be by far the strongest influence. In order to carry the stamp of Art, a film had to be gloomy, politically oriented, and the characters mere puppets speaking the words of their creator, serving the overall scheme and never the private whims of individuals. This trend resulted in a slew of self-important films fostering an unrealistic outlook of reality that stood only by an internal consensus, which insisted on ignoring the logical and psychological inconsistencies.

It was only with the dawn of the new millennium that the glass wall separating reality and screen, audience and characters, life and art were to crack. We were not exactly conscious of that change when Angeliki Giannakopoulos and I decided to establish the first Greek Film Festival in Los Angeles. But it was a serendipitous move, a move that touched the nerve of that change. A new generation of filmmakers suddenly seemed to be free of the memory that had previously become part of a tyrannical subconscious. A fresh look at things local and beyond, a desire to capture life as it is, to understand something but not everything all at once, to create a memorable moment rather than a masterpiece worthy of critical acclaim.

In the environment of artistic discontent and the economic crisis, what some call the Greek Weird Cinema was born. Yorgos Lanthimos’ DOGTOOTH, an ironic allegory about dysfunctional society, which won the Cannes prize Un Certain Regard in 2009 and an Oscar nomination the following year, did not refute the Angelopoulos legacy but transformed it. The schizophrenia between street and screen life was now transferred onto a cinematic apocalypse of the funny and the ridiculous, the dysfunctional and the natural, the sentimental and the numb, the decadence and that new spark of life, the dream of something entirely new, unpredictable and indeterminate. Like Angelopoulos, Lanthimos has his creative followers. Babis Makrides’ L (2012), Athena Rachel Tsangari’s ATTENBERG (2012), and Alexandros Avranas’ MISS VIOLENCE (2013) are just a few bright examples of the new trend. LOBSTER, Lanthimos’ last film, which got the Jury Prize of this year’s Cannes, continues on the same lines. It, too, is about an isolated world run by absurd rules.

In these films, the characters seem trapped in the absurd makings of their own illusions. They speak in a monotonous trail but, whereas Angelopoulos’ characters spoke and moved minimally, in these films the robotic speech is juxtaposed to exaggerated, expressive movement that sometimes turns violent. The Greek screen persona, laboriously created over three decades, is now being deconstructed and examined by the weird ones. We are not what we seem to be – they impress upon us. Who are we? We don’t know but neither do you. What was plain bad acting is now a choice. What was a forced detachment from sentimentalism is now a condition that resembles a deathly illness, a box from which the characters struggle to get away. What was a calculated pessimism is now a force of nature. These characters don’t comment on social injustice; they experience its consequences. What was a deliberate abstinence from the openhearted Greek temperament is now a spasmodic attempt to take it back – and to laugh through all this.

The Greek “weirdness” is but a moment in the history of cinema. What distinguishes it from a legacy is that it makes no claims on what others do, but only recognizes that the new and the unknown may come to us in any shape or form.

The 9th Annual Los Angeles Greek Film Festival (LAGFF) takes place this week Wednesday through Sunday 6/3-7, at the Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood, showcasing 35 films and the 3rd Annual International Project Discovery Forum, LAGFF’s development program of Balkan and international projects. For more information visit www.lagff.org.

Ersi Danou