- Film

May 1968: Philippe Garrel Remembers a Time of Cinema and Revolution

Paris, May 1968, mass protests, street battles and nationwide strikes, a new revolution is on its way, this time, not only a political but social and cultural one. Intellectuals, students and manual workers took the streets engulfing the country by a social upheaval. They were not asking for small changes or a new government, they were asking for a new social structure, freedom of expression, sexual freedom, and a new foreign policy that would not involve Russia and the USA and that would put an end to the colonization of African countries.

Cinema was a fundamental part of the changes to come. Filmmakers like Claude Lelouch, François Truffaut, Agnes Varda, Jean Luc Godard, Alain Resnais and Philippe Garrel, among others, documented the revolt in microfilms (‘cinetrats’). In the meantime, the Cannes Film Festival had to face the protests of filmmakers, film critics, and filmgoers who wanted to boycott the festival. Roman Polanski, Monica Vitti, and Louis Malle resigned as members of the Jury. The festival ended abruptly without winners or any future productions in the industry market.

50 years later, it is inevitable to think of those revolutionary days on the big screen as a path that leads to Philippe Garrel, who not only was a direct witness of that revolution and the favorite son of the movement known as Nouvelle Vague (New Wave) but also an artist who endowed his cinema with a decisive aura that explains that period. Before this edition of Cannes, exactly 50 years after that momentous time, we met with the French director at the latest Buenos Aires Independent Film Festival, where he presented a retrospective of his films, starting with his first feature, Marie pour mémoire, which won the top prize at the 1968 Festival of Young Cinema in Hyères. That same year the filmmaker documented and participated in the students’ uprising, which he would reflect back upon time and again through his career, most notably in his late masterpiece, Les amants reguliers (Regular Lovers). “The people of Paris and I decided that we will not answer questions about May 68, so no problem,” jokes Garrel, who filmed the short film, Act I, at the epicenter of the student’s riots.

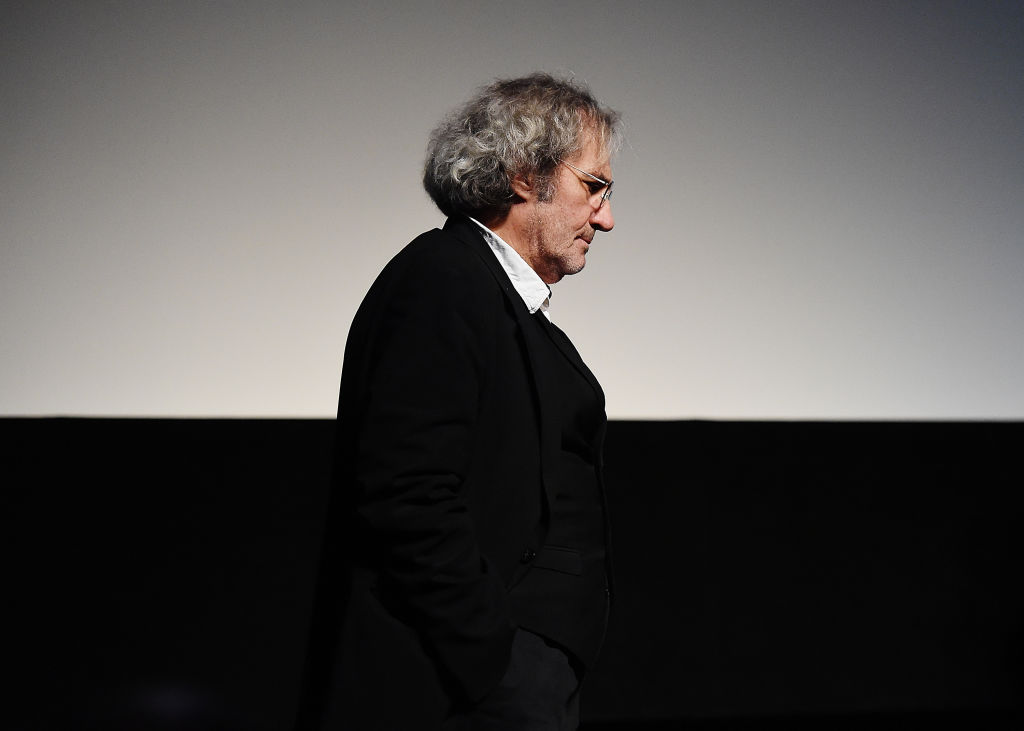

Today, Garrel has the appearance of a tortured, chaotic and existentialist artist, but in person he is polite and very committed to answering in a meticulous way. Son of the French actor Maurice Garrel, Philippe frequently worked with his family, starting with his father, his first wife, Brigitte Sy, his children, Louis and Esther, and Nico, the troubled musician with whom Garrel shared a home, addictions, and the artistic process. Nico appeared in six of Garrel’s features, among them The Inner Scar and The Crystal Cradle. “I always wanted my children to work with other directors before doing it with me, I did not want them to feel suffocated by me, but working with my family made things easier and faster. I usually feel like a painter who portrays his family,” explains the director, whose daughter, Esther, is the protagonist of Lover for a Day, the last film of the trilogy formed by Jealousy and In the Shadow of Women. “I made the first one after the death of my father. I wanted my son to act in the stories of his grandfather’s youth, but with In the Shadow of Women I understood that you cannot work with your relatives when talking about sex and libido (laugh), that’s why I choose actors outside my family,” explains Garrel. “With Lovers for a Day, I realized that it was equally important to work (through) certain issues within the family and others, outside (of) it, which allows me the freedom to do different stories. Instead of concentrating on film and politics as I did in Regular lovers, I tried to unite cinema and psychoanalysis. I wanted to show how unconsciousness and conscience work towards their own antagonistic interests. Here is the daughter of a philosophy teacher who meets her father’s girlfriend, a girl of her age, who was a student of his, and begins a conscious friendship with her. But there is an unconscious rivalry between them. At the end the daughter (is) the cause of the couple’s break up. An Electra complex is revealed. Paradoxically, I know that many people who saw the film liked it, but did not understand it in the sense that I wanted to give. It happens sometimes,” says the director.

When asked about his obsession with black and white, he answers that it was a recommendation of his friend Henri Langlois, founder of the French Cinematheque.

“He was one of the few friends I had in this profession, and he said to me, ‘If you really like to shoot in black and white and in 35 mm, do it, that will never disappear, because it is the origin of the cinema and you cannot deny the origin of something.”

If there is an origin, a starting point to see and understand the world, for Garrel that passes through La Nouvelle Vague, the factory of talent which, in the Sixties, lighted up a new cinema in Paris. “For most people, cinema ends with the Nouvelle Vague. For us it is the opposite, cinema begins with the Nouvelle Vague.”