- Film

Filmmakers’ Autobiographies:Kurosawa,“Something Like an Autobiography”

In 1916, the Ushigomekan cinema, in Tokyo’s Kagurazaka district, used to play only foreign films. This is where six-year-old Akira Kurosawa remembers seeing “a lot of American action serials, like The Iron Claw, Hurricane Hutch, The Tiger’s Footprints, many others starring William S. Hart and the French crime-adventure Zigomar by Victorin Jasset, ” But, as he confesses in “Something Like an Autobiography”, published in 1981, “my contact with the movies at that age has, I feel, no correlation to my later becoming a director. I simply enjoyed the varied and pleasant stimulation added to ordinary everyday life by watching the motion-picture screen. I relished laughing, getting scared, feeling sad, and being moved to tears.”

In 1974, inspired by Jean Renoir’s recently published autobiography, Kurosawa started working on his own. The result, originally serialized in the Japanese magazine Shukan Yomiuri, is a sensorial and vividly evocative account of his life, from early childhood, growing up in the Taisho era, to 1950 with the making of his seminal masterpiece Rashomon.

Reminiscing about his boyhood, he muses that “perhaps it is the power of memory that gives rise to the power of imagination.” On September 1, 1923, the Great Kanto Earthquake devastated most of Tokyo. His elder brother forced him to take a walk amongst the ruins, ordering him to not look away from the horror. There, “amid the expanse of nauseating redness lay every kind of corpse imaginable.” A traumatizing event that left an indelible mark. By eighteen, he was interested in calligraphy and painting and considered making a living out of it. An avid moviegoer, he scrupulously lists more than a hundred titles that had impressed him. Murnau’s Sunrise, Lewis Milestone’s All Quiet on the Western Front and The Front Page, René Clair’s Sous les toits de Paris, Josef von Sternberg’s The Blue Angel and Shanghai Express, Chaplin’s City Lights, and Pabst’s The Three Penny Opera.

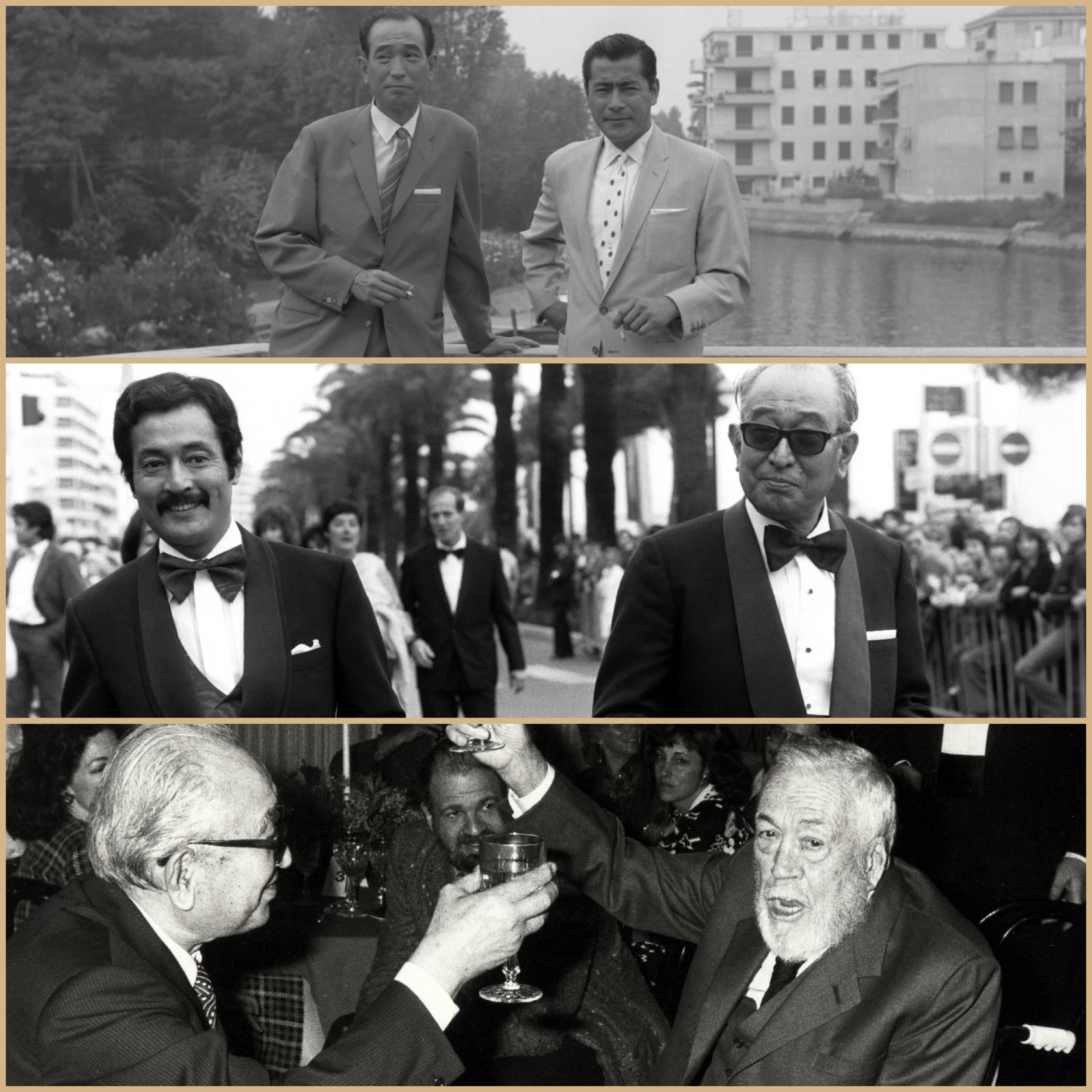

From the top: with Toshiro Mifune (right), in Venice, 1960; with actor Tatsuya Nakadai, star of Kagemusha, walking the red carpet towards the Palais, Festival de Cannes, 1980; toasting with John Huston in Los Angeles, at the 38th Directors Guild of America Honors Akira Kurosawa, 1986.

hulton archives/ Bertrand LAFORET/Gamma-Rapho/ron gallela/getty

In 1929, gradually losing confidence in his painting abilities, he joined the Proletarian Artists’ League, a left-wing organization. “With my head crammed full of art, literature, theater, music, and film knowledge, I continued to wander, vainly looking for a place to make use of it.” It took a while, after a period of salad days and lean years, until all changed in 1935 when he was hired as assistant director at the Photo Chemical Laboratory Film studio, later to be renamed Toho. “There I met the best teacher of my life, Kajiro Yamamoto,” a prolific and renowned director who helped him developed his screenwriting and editing skills. Under his tutelage, he learned the power of combining sound effects and music to enhance the impact of visual images.

By 1943, Kurosawa had helmed his first feature, Shanshiro Sugata. “It was chance that led me to become a film director, yet somehow everything I had done prior to that seemed to point to it as an inevitability. I cannot help wondering what fate had prepared me so well for this road I was to take in life. All I can say is that the preparation was totally unconscious on my part.”

Dealing with censorship during the war, and then in U.S. Army-occupied Japan, was a constant struggle for him and others like Yasujiro Ozu, Kenji Mizoguchi and Mikio Naruse whose names would later put Japanese cinema on the world map. Kurosawa was determined to forge on, managing to impose his unique vision and style despite strict rules that forbade showing certain images and themes. In 1948, Drunken Angel marked the first of 16 collaborations between Toshiro Mifune and Kurosawa that would end in 1965 with Red Beard.

The then-unknown actor had come to his attention two years earlier while auditioning at the studio which was looking for new faces. “I was transfixed,” he remembers. “A young man was reeling around in a violent frenzy. It was as frightening as watching a wounded or trapped savage beast trying to break loose. I found him strangely attractive. He possessed the kind of talent I had never encountered in the Japanese cinema. The speed with which he expressed himself was astounding.”

Rashomon – at first the Daiei studio management was not happy with Kurosawa’s conceptual idea. “They said the content was difficult and the title had no appeal,” he recalled. The story was deemed too confusing. The day before filming started, he had to clarify again the psychological dimension of the film. “Human beings are unable to be honest with themselves about themselves,” he told his three assistant directors. “They cannot talk about themselves without embellishing. The script portrays such human beings – the kind who cannot survive without lies that make them feel they are better people than they really are. You say you can’t understand this script at all, but that is because the human heart itself is impossible to understand.”

While scouting locations in Kyoto and nearby Nara where the filming took place in the summer of 1950, Kurosawa was impressed by the imposing Ninnaji and Todaiji Temples. That was the inspiration for the gigantic gate used as one of the main decors. A major concern was capturing “the light and shadows” in the forest, the keynote of the movie as he envisioned it. “I solved the problem by filming directly into the sun, something considered taboo because it was thought the sun’s rays shining into the lens would burn the film in your camera.” To breathtaking effect. Each day, because of leeches falling down the trees and crawling around, the crew had to cover their arms, necks, and ankles with salt, the best repellent. To make the torrential rain sequence more dramatic, black ink was added to the water sprayed by fire hoses at full force.

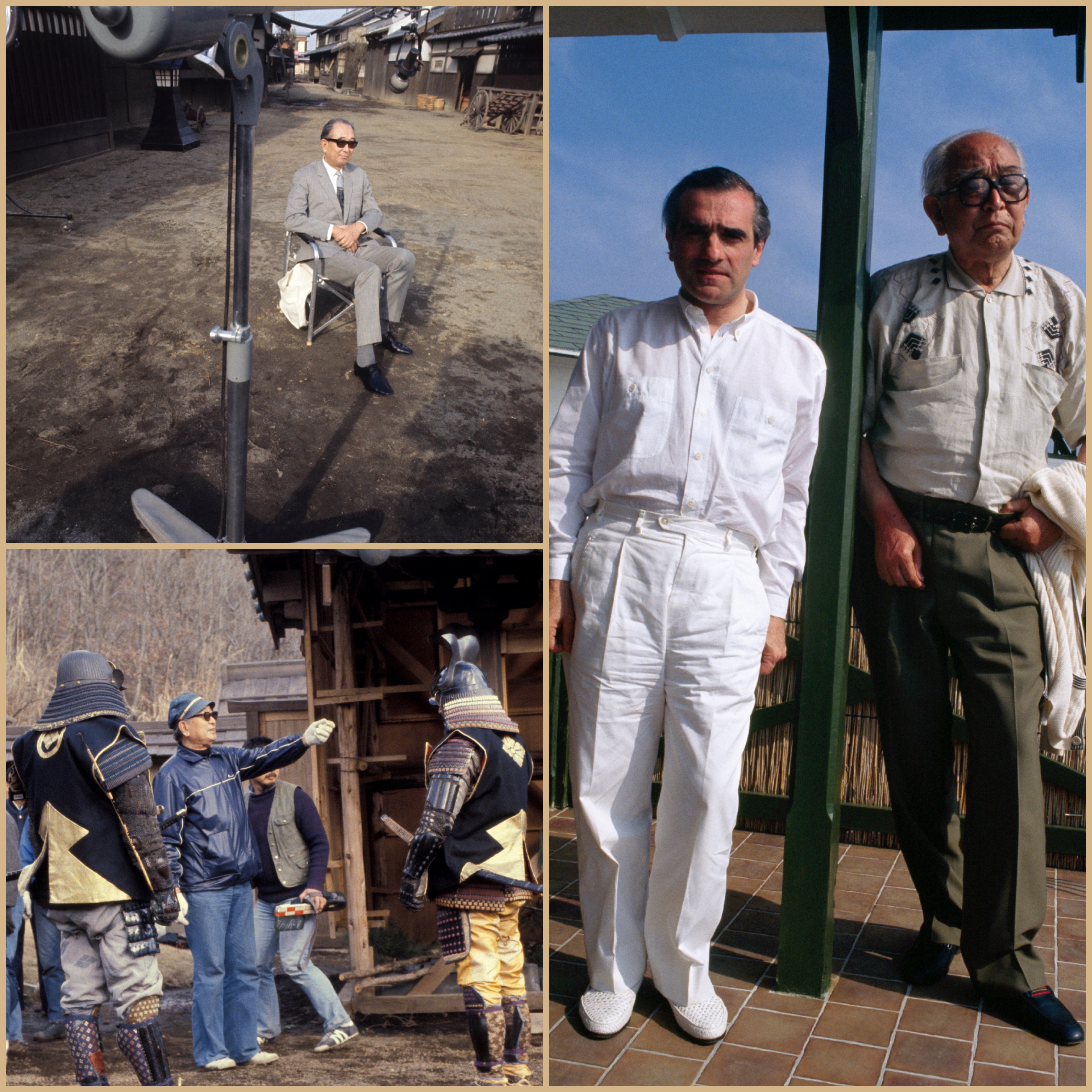

Clockwise from top left: being interviewed on the set of Dodes’ka-den, 1970; with Martin Scorsese at the 1990 Cannes Film Festival, promoting Dreams, in which Scorsese played the role of Vincent Van Gogh; on the set of Kagemusha (The Shadow Warrior), 1980.

walt disney television/christophe d’yvoire-sygma/kurita kaku-gamma rapho/via getty images

To his surprise, (he did not know the movie had been entered in the competition) Rashomon won the Golden Lion at the 1951 Venice Film Festival and, a year later, the Academy Award for foreign language film. But what puzzled him the most was that “Japanese critics insisted that those two prizes were simply reflections of Westerners’ curiosity and taste for Oriental exoticism, which struck me then, and now, as terrible. Why is it that Japanese people have no confidence in the worth of Japan? Why do they elevate everything foreign and denigrate everything Japanese?”

When his book came out, Kurosawa was considered the greatest living Japanese director. The influential master and unrivaled Mt Fuji of cinema. Kagemusha had won the Palme d’Or at the 1980 Cannes Film Festival and was nominated for the Golden Globe. Many of his previous films, Throne of Blood, High and Low, The Hidden Fortress, Yojimbo, are enduring classics, with dazzling groundbreaking narrative technique in flagrant contrast with the mainstream cinema of his country at the time. As he had said in an interview, “Japanese films all tend to be assari shiteiru (light and with no distinctive flavor) just like Ochazuke (a traditional comfort food made of green tea over rice) but I think we ought to have richer food, richer films.” That’s something he strove for all his career.

“I have come this far in writing something resembling an autobiography,” he concludes, wistfully, “but I doubt that I have managed to achieve real honesty about myself in its pages. I suspect that I have left out my uglier traits and beautified the rest. Rashomon became the gateway for my entry into the international film world, yet, as an autobiographer, it is impossible for me to pass through the Rashomon gate and on to the rest of my life. Perhaps someday I will be able to do so.”

In the epilogue, he has one piece of advice for the reader eager to know more about him. “I am a filmmaker: films are my true medium. There is nothing that says more about its creator than the work itself.”