- Industry

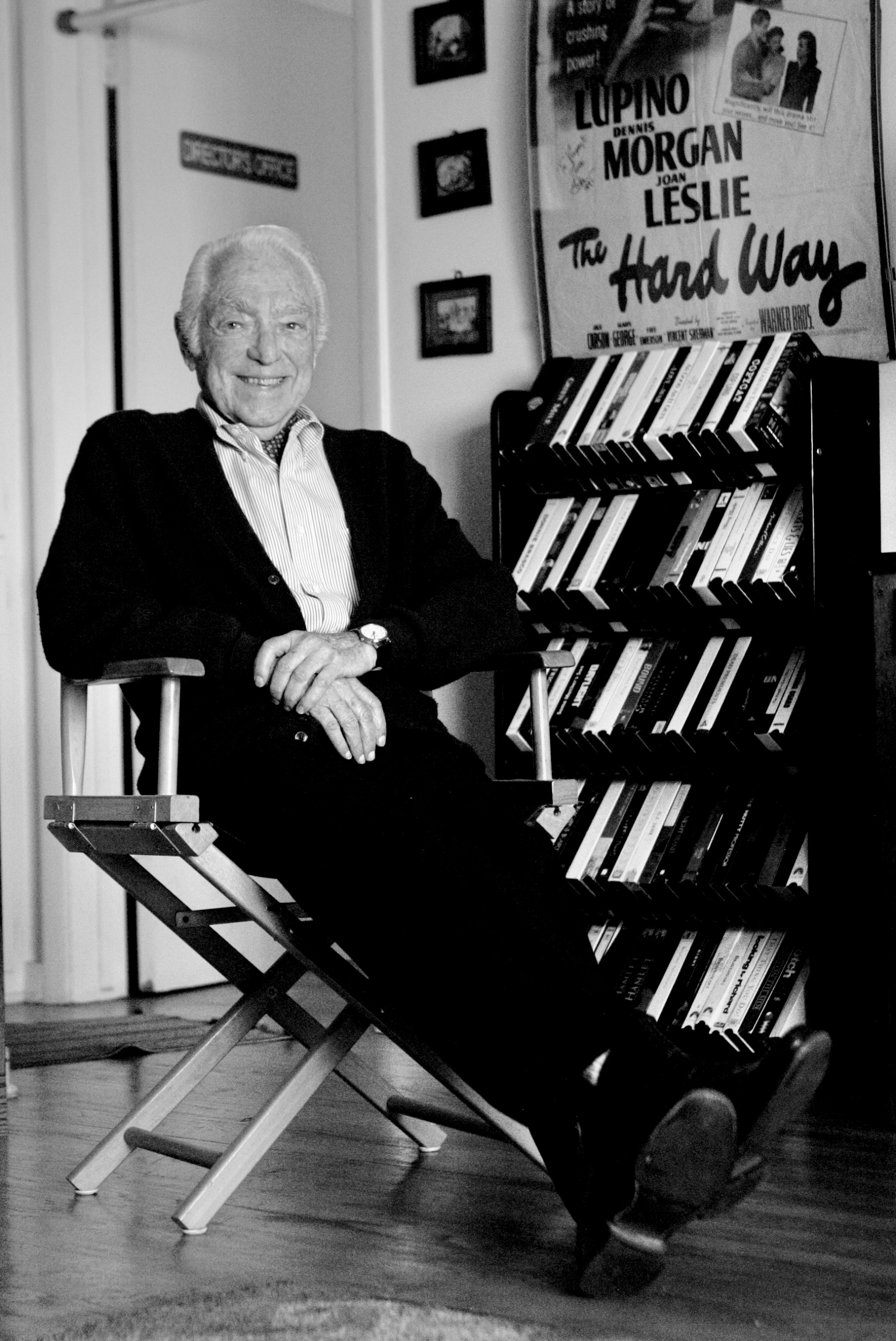

Filmmakers’ Autobiographies: Vincent Sherman’s Studio Affairs

In 1996, ten years before his passing at age 99, Vincent Sherman published his autobiography simply titled ‘Studio Affairs: My Life as a Film Director’. Today, his name might not be remembered as some of his more celebrated colleagues of Hollywood’s Golden Age, but he was, as Oliver Stone rightly called him, “one of the great craftsmen from the old studio system.”

Looking back, as he approached his ninetieth birthday, he notes that “although my films were not landmarks, they did win some recognition and from the fan mail I have received over the years and from all over the world, I have reason to believe they provided a few hours of entertainment.” In a career spanning over thirty years, he was able to tackle a variety of genres, efficient and equally at ease with swashbuckling adventures, romantic melodramas, hard-boiled crime thrillers and Westerns. Today, only hardcore cinephiles would know some of them. All Through the Night, Harriett Craig, The Hasty Heart, Goodbye My Fancy, The Naked Earth, Nora Prentiss, The Second Time Around.

As a young Jewish boy growing up in Vienna, Georgia, Abe Orowitz could have never predicted the twists and turns that ultimately brought him to Hollywood. At twenty-one, he remembers, “I decided to give up the study of law, go to New York, and seek fame and fortune in the theater.” An agent advised him to change his name. He was now Vincent Sherman. Soon he started writing, acting in and directing plays, touring all over America. In 1934, he was invited to Hollywood where William Wyler cast him opposite John Barrymore in Counsellor at Law.

Fast forward three years. By 1937, Sherman is under contract at Warner Brothers where he quickly developed a reputation for his consummate skills at reworking flawed scripts. Two years later he directed his first feature for the studio. The Return of Dr. X starring Humphrey Bogart as … a criminal who had died in the electric chair but was brought back to life. “Obviously, it was a hokey story and cornball role,” Sherman acknowledges, “but Bogie and I were both from the theater and were used to working seriously on whatever was handed to us, so we did our best to make it as palatable as possible.”

That was his professional motto. And his memoirs offer a valuable insight into the inner workings of the Dream Factory at its most productive. He made twenty films for Warner Brothers. But, after all those years, what still irked him, is “the enduring assumption made by many film savants and critics writing often condescendingly that contract directors at the major studios were forced to shoot according to a set of rules laid down by the moguls.” He insists it was never the case for him, that he got along with Jack Warner and knew how to deal and adapt with “his many likes and dislikes.” His approach was a simple one, dictated by a few basic precepts. “Above all, a director must be a good storyteller. He must know how to establish interest in his characters and their problems. He has to be able to work with actors, to give them a feeling of confidence and security. Audiences should be unaware of the mechanics of filmmaking.”

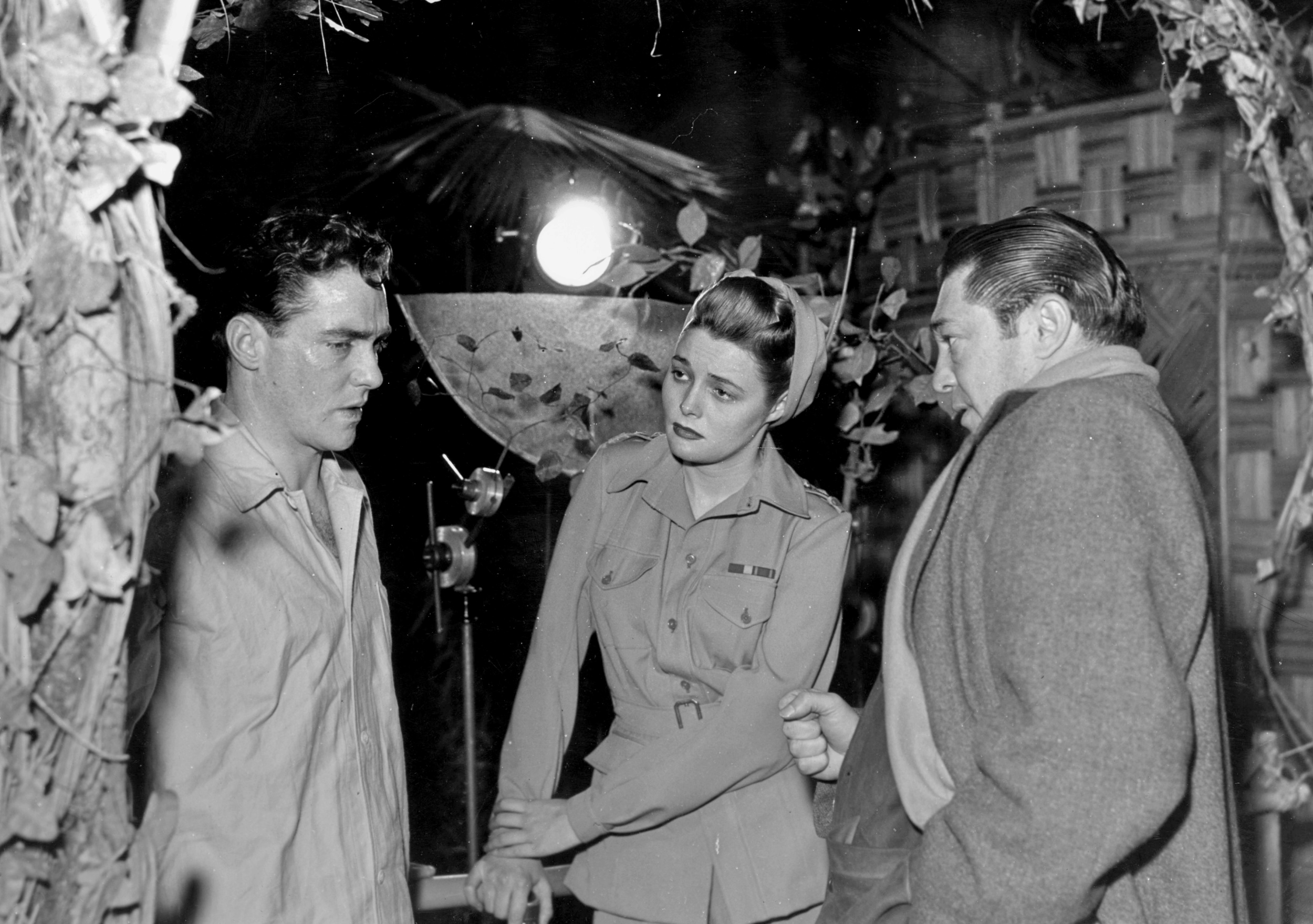

On the set of The Hasty Heart (rigt) directing actors Richard Todd and Patricia Neal, 1949.

Picture Post/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

The affairs mentioned in the book title? A first, and brief one, with Bette Davis in 1944, during the making of Mr. Skeffington, their second film together following Old Acquaintance. “It was a turbulent, frustrating experience and I vowed to never again be emotionally involved with any actress I was directing.” But it was not to be!

Joan Crawford. Their three-year liaison began in 1950, soon after production of The Damned Don’t Cry began. “She was the ultimate star, magnetic and glamorous,” he writes. “However, behind a façade of toughness, I sensed an incurable romanticism.” And, as he quickly found out, a woman for whom, “sex was, primarily, an ego trip.” He describes in suggestive details several of their many steamy trysts and carnal interludes. They made three films together. She wanted him to divorce his wife and marry her. Sherman declined. Later, she would say he had been one of her favorite directors. Maybe not only because of his prowess behind the camera.

1952. Another mansion, another bedroom, another lonely glamorous star. This time it is Rita Hayworth. After four years away from Hollywood, now divorced from Prince Aly Khan, she is about to make her comeback in Affair in Trinidad. Sherman quickly realizes she is quite vulnerable. “Insecure about her looks and at the prospect of facing the camera again, in need of reassurance, comfort, and company.” One night at her home, he is happy to provide all of it and a bit more. The film was a box-office success. Rita was back in all her resplendent sultriness. Mission accomplished for the studio. To the readers who might be offended by those revealing intimacies, Sherman offers no apologies. “Excluding those episodes would be to draw a veil over some of my most vivid experiences.”

Then there is Errol Flynn, who asked him to direct The Adventures of Don Juan, a big expensive production. In 1948, Flynn was past his prime, ‘after having been Warner Brothers’ biggest moneymaker but at the time, (he’s become) the studio’s biggest headache. Women and liquor were the devils that tormented him.” And still did as Sherman would uncover during the chaotic nine months needed to complete the picture. Their first meeting took place when Flynn was being fitted for his costumes. Adamant that his jacket be shortened to only partially cover his crotch, a puzzled Sherman nonetheless agreed. Once filming started, “we occasionally had trouble,” he remembers facetiously, “especially in side angles, the protrusion was too pronounced, and we had to change the lightning or else I had to stage the scene differently.” When Sherman suggested that Flynn do like dancers and “tape his thing up and wear a jockstrap or codpiece over it,” he got a non-negotiable response. “My dear boy, I’ve done many things for Warner over the years, but I’m damned if I’ll tape up my cock for them.”

He remembers fondly working with Clark Gable on Lone Star in 1951. “He was, like Errol Flynn, a much better actor than he was ever given credit for. In addition to his gracious and charming modesty, he had a wonderful sense of humor.” Like many during the red scare of the fifties, Sherman was targeted by the House Un-American Activities Committee, owing in part to his support to the leftist WPA (Works Progress Administration) Federal Theater project in New York, two decades earlier. As a result, he was put on a grey list, unable to find work for two years until 1955. “A harrowing experience as Hollywood went through one of the most shameful periods of its history.”

With Angie Dickinson and Don Ameche on the set of A Fever In The Blood, 1961.

getty images

After the 1969 release of Cervantes, Sherman would never direct another picture for the big screen, ending his career as a successful television director. “Grateful to keep learning in a new medium.”

At the twilight of his long life, he is candid on some of his regrets, especially having “not fought harder to get The Treasure of the Sierra Madre and Casablanca and that I accepted many second-rate assignments.” Of all his films, he is particularly proud of The Hard Way, how he was able to help calibrate the performance of its often recalcitrant star Ida Lupino and that he lived to see the movie rediscovered 53 years later at the 1995 Telluride Film Festival.

He never forgot D.W. Griffith addressing his peers in the late 40s. “Films speak a universal language, and you have in your hands the power to change the world.”

As he concludes his memoirs, he has one last wish. “I can only hope that all of us who are in the field of entertainment and communication will use our talents to oppose hatred, violence, racism, greed, and corruption, to become more conscious of our environment, to support education, and to help those who are less fortunate than we are…” A message that eerily resonates now more than ever.