- Industry

Out of the Vaults: “The Long Voyage Home”, 1940

The instrumental strains of “Harbor Lights,” the popular song from 1937, sound over the opening prologue: “With their hates and desires men are changing the face of the earth – but they cannot change the sea. Men who live on the sea never change – for they live in a lonely world apart as they drift from one rusty tramp steamer to the next, forging the life-lines of Nations.”

The camera moves back across an iridescent sea with a hulking ship in the background to the shore where native women undulate to a haunting melody. The scene then shifts to the Glencairn where rough-hewn men with weather-beaten faces listen to the music.

So, begins John Ford’s The Long Voyage Home, starring John Wayne. But neither men are the real star of the picture. That star is cinematographer Gregg Toland. It’s rare that a director shares credit on the same card with his cinematographer. Ford does it here, as did Orson Welles on Citizen Kane a year later, again with Toland.

This black and white film is a masterpiece of visual expressionism, with Toland experimenting with various lenses to achieve deep focus, using high contrast lighting and hardly moving the camera so every action is captured within its frame. We see the decrepit ship become a thing of beauty with the moonlight on its rails and splashed across its deck, the fury of a storm battering shimmering water against the window of the bridge, the cobblestones of a backwater city gleaming through the legs of the sailors passing, the light and shadows falling on the faces of the sailors as they huddle in their cramped quarters below decks, the camera locked on the foot of a sailor as he falls backward to his death.

Wayne told his biographer Maurice Zolotow: “Usually it would be Mr. Ford who helped the cinematographer get his compositions for maximum effect … but in this case, it was Gregg Toland who helped Mr. Ford. The Long Voyage Home is about as beautifully photographed a movie as there ever has been.”

Based on four one-act plays by Eugene O’Neill, the screenplay was written by Dudley Nichols, a friend of O’Neill’s. O’Neill was a seaman himself in his early days, and his own experiences informed his plays. He said that this was one of his favorite films and that he wore out the print presented to him by Ford from multiple viewings.

The action in the story was moved from WWI to the beginning of WWII. The Glencairn is bound for England from the Caribbean and stops in Baltimore to pick up ammunition, then has to pass through a no-man’s land in the Atlantic patrolled by Nazi ships and aircraft on its way to Southampton. The loneliness of these lifelong sailors is shown in their lives aboard, discounted by their captain, unable to protest the dangerous cargo or the hazardous route through the Atlantic, cramped into meager quarters, sustained only by the friendships among them, doomed to repeat the voyages over and over as none has a family to go back to, save one.

That one is the Wayne character, a young Swede named Ole, a very different role from the cowboys he was used to playing, but later considered it one of his best performances. He had to be persuaded to take the part by Ford as he was worried about the Swedish accent. Thomas Mitchell (Scarlett’s father in Gone With the Wind), is really the leader of the ensemble, the old Irish salt Driscoll, who keeps the band together through the drinking and brawling. Other standouts include Ian Hunter as Smitty, the Englishman who is accused of being a German spy in a heartrending scene, and Ward Bond as Yank, who exemplifies the struggle to live that these men are up against every day. Mildred Natwick has a fine turn as a prostitute.

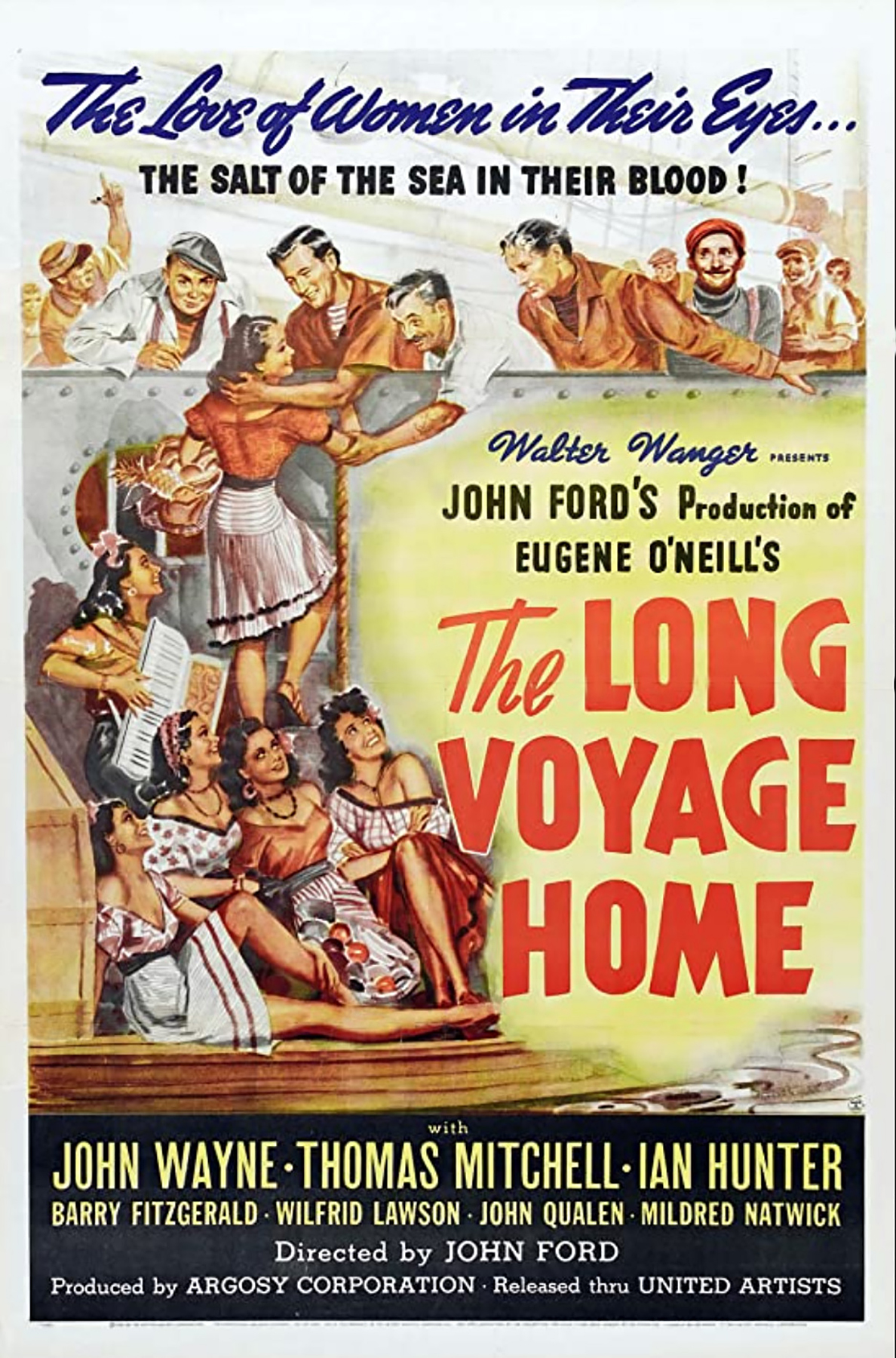

The film was not a big success on its opening, due perhaps to its downbeat story and lack of a love interest. Its poster is actually quite misleading, featuring the seamen hoisting up several brightly dressed island girls onto the boat under the caption “The Love of Women in Their Eyes … THE SALT OF THE SEA IN THEIR BLOOD!” It actually lost $225,0000 in its initial run. But it received excellent notices and earned several Oscar nominations – Best Black and White Cinematography, Best Film Editing, Best Original Score, Best Special Photographic Effects, Best Sound, Best Screenplay, and Outstanding Production (Best Picture). (Ford won for Best Director for Grapes of Wrath that same year; Toland was his cinematographer on that as well.) The National Board of Review named it one of the ‘ten best’ of 1940.

As a publicity stunt, producer Walter Wanger paid $50,000 to nine well-known artists of the time to paint scenes from the movie and the actors in character. The paintings were featured in ‘Life’ magazine and displayed in museums across the country as a traveling exhibit.

was restored by the UCLA Film & Television Archive with funding provided by the Hollywood Foreign Press Association and The Film Foundation. The Archive holds excellent safety preservation picture and sound master positives made from the original elements; however, there are no 35mm prints of the film currently available. The sound was re-recorded from the variable area and variable density track positives to WAV files, and was sequenced and synchronized. Once the digital restoration of the soundtrack was completed, a new optical soundtrack negative was created along with a mag track for preservation. A new polyester 35mm duplicate negative was created from the fine grain master positive and that, along with the restored track negative, will be used to create new 35mm prints for archival screenings.

An excellent Criterion print is available on HBO Max.