- Film

Filmmakers’ Autobiographies: King Vidor’s “A Tree Is a Tree”

Paris. Summer of 1928. King Vidor was sitting at the terrace of the Café de la Paix, on Place de l’Opéra, preoccupied with the latest Variety headline which read: “Pix Industry Goes 100% for Sound.”

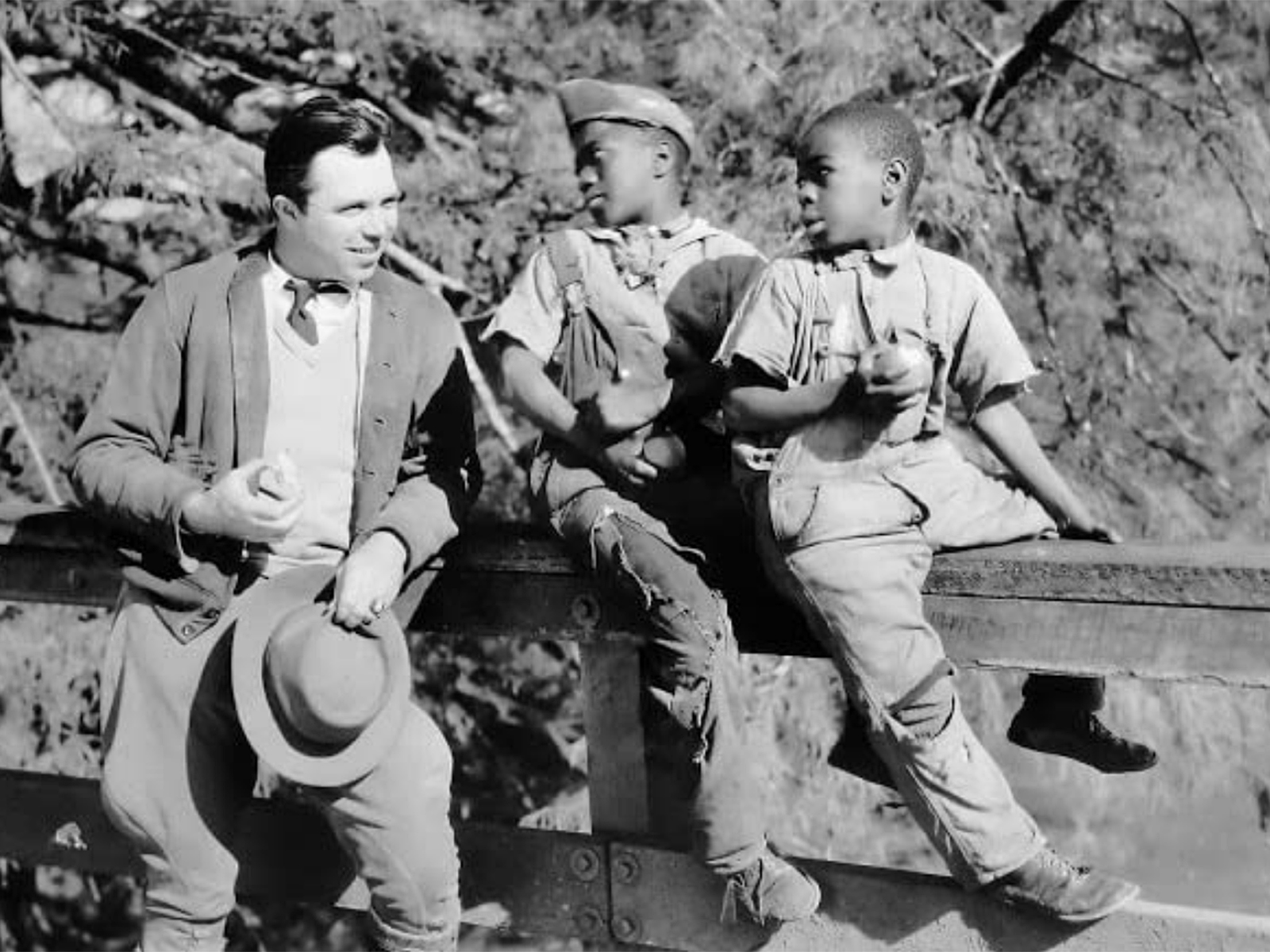

After two months of hobnobbing with the likes of F. Scott Fitzgerald, discussing future plans of making a film together in the City of Lights, watching the daily ballet lesson of his wife Zelda, visiting expatriate Silvia Beach who introduced him to James Joyce and Ernest Hemingway, the director felt the urgency to head home, back to Hollywood. “A major transition had taken place in the motion picture industry,” he writes in “A Tree is a Tree,” his memoirs published in 1953, at the twilight of his career. “I was excited, but greatly saddened. I realized that much magic would disappear from the screen, and that also new techniques would have to be discovered, invented and established. The dragon of sound must be met head-on and conquered.” And he did just that. A year later Vidor would direct his first talkie, the ground-breaking all-Black cast musical Hallelujah.

By then he was already a very established director with twenty-six silent movies to his credit which helped seal his reputation as one of the most reliable filmmakers equally at ease in assorted genres: Billy the Kid, The Big Parade, The Champ, The Crowd amongst some of the most memorable.

Flashback. Growing up in Galveston, Texas, where he was born in 1894, Vidor vividly remembers seeing Georges Mélies’s A Trip to the Moon at a local nickelodeon when he was fifteen. His fascination with moving images started then. He got a job working the projection booth. “In the twelve hours the theater was in operation, I watched the same film twenty-four times. Early comedies that were practically all made in France and starred Max Linder. I learned much about pantomime from him as I sat there in the dark.”

Still, he could not see how that could translate to a vocation. “I thought much about becoming an automobile racing driver, or perhaps, an aviator and my father was trying to arouse in me an interest in engineering.” Everything changed for him when a friend built his own makeshift movie camera. To test it, they chose a beach battered by a hurricane, and by accident recorded the destruction of dwellings by gale-force winds. “The film developed and in spite of blurred images, it was shown all over the state. It made an indelible mark on my psyche. I was impatient to get started in this new profession.”

By 1915, he and his wife Florence, who intended to make it as an actress, were on their way to California in a Ford Model T with barely enough money to survive. They settled in Hollywood, in a boarding house just around the corner from the humongous Babylonian set built by D.W. Griffith for Intolerance. “When actual filming was in progress, I spent many profitable hours watching the great D.W. at work.”

Vidor made the rounds at the studios, looking for a job. He got one at Universal as a company clerk. He had other ambitions and started to peddle scripts. But he was most anxious to direct a full-length feature. Privately funded by a group of ten Christian Scientist doctors, The Turn in the Road was filmed at the end of 1918. After it opened in Los Angeles the following March, Vidor found himself very much in demand. He reflects on his aim at the time: “I always felt the impulse to use the motion-picture screen as an expression of hope and faith, to make films presenting positive ideas and ideals rather than negative themes. When I have occasionally strayed from this early resolve, I have accomplished nothing but regret.”

He goes on to recount the impact of his increasing success, the making of some of his movies, the dealings with producers and studio heads like Samuel Goldwyn and Irving Thalberg… Working with Lillian Gish proved a challenge on the set of La Bohème. Her approach to playing Mimi almost destabilized Vidor at first. But he admits great admiration for the way she prepared for her death scene by not drinking for three days before it was shot. Until then, he alarmingly watched her “growing paler and paler, thinner and thinner.” The result was effective. She was ready for her scene, all in “sunken eyes, hollow cheeks, lips curled outward and parched with dryness.” Once he said “cut” after the take, “there was no one on the set whose eyes were dry.” As he remarks drolly, “the movies have never known a more dedicated artist.”

He recalls his enduring friendship with John Gilbert, and their many collaborations, notably in 1925 on The Great Parade. Vidor wanted him to play against type and let go of the image of “The Great Lover”, he had been building on and off the screen. “In the part of the American doughboy, opposite Renée Adorée, he would use no make-up, wear an ill-fitting uniform, dirty fingernails and a sweaty, begrimed face, for a more down-to-earth characterization.” Gilbert resisted at first but was quickly convinced it would work for the role. As Vidor remarks, “the enormous success of the movie helped him skyrocket to the height of his popularity.”

Colorful anecdotes abound throughout the book. On Gilbert’s tennis court at his Bel-Air home, he taught Greta Garbo how to play. “She was a bulwark of strength at the net.” Charlie Chaplin once gave him an ill-fitting haircut. William Randolph Hearst relentlessly courted him with invitations to his San Simeon estate, to convince him to cast his long-time mistress Marion Davies in several comedies. He did and enjoyed working with her. David O. Selznick wanted him to helm a South Seas romance with Dolores del Rio and Joel McCrea under the RKO banner. Bird of Paradise was filmed on location in Hawaii, and he details a production dogged by logistical and weather-related problems.

Unfortunately, Vidor doesn’t address the very daring underwater sequence with his two stars, how Dolores del Rio was convinced to be filmed naked in an elegiac moonlight swim.

This is one of the most frustrating aspects of his autobiography. One wishes for instance that instead of just mentioning their names, he had disclosed more details about directing Barbara Stanwyck in Stella Dallas, Clark Gable in Comrade X, Jennifer Jones and Gregory Peck in Duel in the Sun or Bette Davis in Beyond the Forest. Could it be they did not get along? And because, at the time of the book’s publication, those stars were still alive?

He is more eloquent about Gary Cooper during the making of Wedding Night in 1935. He tells of the actor’s difficulties with his lines, and that he worried when he heard him mumble, take after take. “I determined I must do something about my friend’s diction, memory and delivery. But Cooper was Cooper; no wheedling on my part could bring the slightest change.” So, he was amazed watching the rushes of the first day’s work, as the screen revealed his “highly complex and fascinating inner personality”. Concluding matter-of-factly that “the psychoanalytic power of the camera can prove either beneficial or detrimental to a performer. In Cooper’s case it was the making of the film.”

He lyrically explained what kept him going for so many years. “A future film is a series of wishes, of hopes, of meeting, of talks. A succession of ambitions and desires, elusive fantasies, (…) Work and inspiration, trust and patience. Setbacks and successes, starts and completions. It means a lot of worries, but it’s a wonderful feeling which I hope I shall always be eager for…”

King Vidor wrote, “A Tree is a Tree” when he was fifty-nine years old. He had just released his latest film, Ruby Gentry with Jennifer Jones and Charlton Heston. He only alludes to the movie to say, “it did well at the box-office, but Bwana Devil did better.” Witnessing firsthand “the end of the Golden Age of Hollywood with the advent of television,” he worried that “the art of motion picture seems seriously threatened with extinction.” He ponders about the challenges directors will face with the newly invented CinemaScope and the 3D craze. He directed only two more large-scale productions in the late fifties, War and Peace and Solomon and Sheba, before retiring. He appeared in a small part in James Toback’s Love & Money, released in 1982, the year of his death.

As he reflects on his life and career, he concludes with one last comment. “Here is the lesson I have gained from this seemingly irrelevant parallel between the world of the moving picture and what we call the natural world. Both are our oyster – palatable or bitter, as we make them. The magic of the movies is obvious, the illusion of our other world more subtle. We have been given the privilege of choice in the magic story we write. Life has designated us all magicians. The illusion must not be permitted to dictate to its master.”

And for an explanation of the title? It came from the answer given by producer Abe Stern who was asked by a director for a more authentic-looking location to film a sequence. His response: “A rock is a rock, and a tree is a tree. Shoot it in Griffith Park!”