- Film

Docs: “Bernstein’s Wall” – Celebrating the World-Renowned Composer

Leonard Bernstein was one of the most prodigiously talented and successful musicians in American history. A renowned conductor and composer, a music educator and author, a humanitarian activist. How do you begin to cover such a rich and multi-faceted life in a single feature?

Douglas Triola, the director of Bernstein’s Wall, a documentary that premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival, has decided to narrow his range and focus on the legendary man’s social, political, and humanitarian activities while dealing more briefly with his musical work, which was unusually diverse.

This might prove frustrating to Bernstein’s global fan base since among the musician’s many achievements, he was the first American-born conductor to lead an American orchestra, the New York Philharmonic, and the first American musician to receive international acclaim.

Tirola’s documentary is more of an intimate portrait, a first-person appreciation, aimed at disclosing the passions that drove the person, shown largely through his own words and personal phrases. A good portion of the feature consists of TV interviews, information footage, motion pictures and audio clips, including a variety of elegant graphics.

Born in 1918 as Louis Bernstein in Lawrence, Massachusetts, he was the son of Ukrainian-Jewish immigrants. During his early youth, his only exposure to music was the household radio and music on Friday nights at Congregation Mishkan Tefila in Roxbury, MA.

He studied music at Harvard and afterward conducted research in Philadelphia’s Curtis Institute of Music and the Tanglewood Music Heart in the Berkshires.

Bernstein credits the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s director Serge Koussevitsky with educating him about the basics of conducting, and Aaron Copland as a crucial mentor in composition.

He wrote in many styles, producing symphonic and orchestral music, ballet, film scores, theater music, choral works, opera, and chamber music. His works include three symphonies, Chichester Psalms, Serenade after Plato’s “Symposium,” the original score for Kazan’s 1954 Oscar winner On the Waterfront, and for theater works including On the Town, Wonderful Town, and Candide.

His most popular work was the Broadway musical West Side Story, which was made into a 1961 Oscar-winning picture, directed by Robert Wise. (There’s high anticipation for Spielberg’s new version, set to open in December).

Bernstein was the first conductor to share music on television with a mass audience. Through dozens of national and international broadcasts, including the Emmy Award-winning Young People’s Concerts with the New York Philharmonic, he made the most rigorous classical music an accessible adventure for the lay public.

Most of the story is told in Bernstein’s own words, he himself serving as the subjective narrator of his life. Much of it is taken from a 25-hour interview conducted over the summer of 1968 when Bernstein invited a journalist friend to join him with his family on a vacation in Italy. These tapes allow rather direct access into some personal moments.

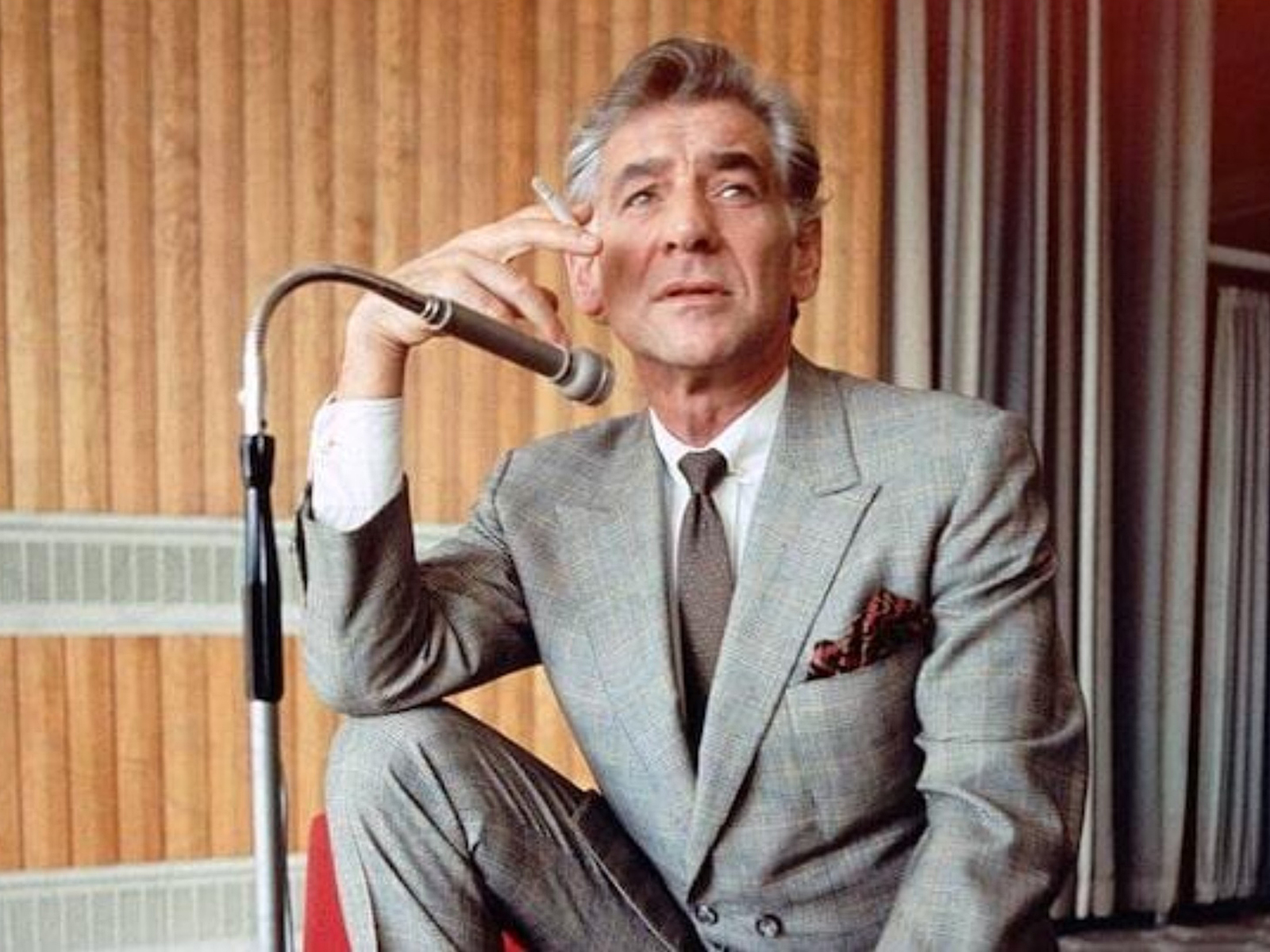

With the help of Bernstein’s last assistant, the Bernstein family, archivists and museum curators, the director have retrieved audio and filmed recording of him talking about his philosophy, politics and personal life; Bernstein is rarely seen without a drink or cigarette, and he’s always thinking.

Bernstein wrote over 10,000 letters in his lifetime, in which he shared his fears and concerns, particularly about McCarthyism, the Blacklist, his marriage and his sexuality.

Tirola opens his feature with one of Bernstein’s direct-to-camera lectures, beginning with the 1954 CBS arts collection Omnibus, which covered a wide range of music: classical, jazz, musical theater and opera.

Clips present him to be a singular personality – a sort of rock star – as dynamic in his regular life as he was on the podium. He’s depicted as a charismatic lecturer and a passionate advocate for social change, for utilizing the arts and humanities for freedom and equality, peace and unity.

There are only brief interview snippets with Bernstein’s sister and his wife, with whom he had a long and complicated marriage due to his homosexuality. The documentary acknowledges that Bernstein was homosexual and that his spouse of 27 years, Felicia Montealegre, was conscious of his sexual orientation. In one poignant exchange of letters, Felicia speaks candidly about his sexuality and the obstacles created by his double life, conceding his freedom, “with no guilt and no penalties.” Yet there’s also evidence that he was a loyal husband (he took care of the terminally ill Felicia until her death), who found fatherhood to be fulfilling.

Bernstein’s leftist political leanings are detailed, from his relatively unscathed brush with the Home Un-American Actions Committee to his participation in civil rights marches and anti-Vietnam protests. He organized a social gathering in 1970 to boost protection funds for unjustly imprisoned members of Black Panther, an event that made him the target of harsh media criticism.

Both as director of the New York Philharmonic and afterward, Bernstein courted – and was courted by – celebrities, including politicians, most notably the Kennedys. At Jacqueline Kennedy’s request, he composed the theater piece Mass for the inauguration of the Kennedy Center in 1971. Bernstein calls Mass “a press release in regard to the temporariness of energy.” This event drew suspicion from Richard Nixon and his honcho Haldeman, who was heard warning the president that the work’s political overtones would make it unwise for him to attend.

As noted, Bernstein’s contributions to musical theater – including West Side Story and On the Town – are not thoroughly covered here. Other cherished compositions, such as Candide and Wonderful Town, are not even mentioned.

The footage mirrors the pace of Bernstein’s life, which, like a symphony, moved between furious excitement and quiet intimacy. Triola makes the case that Bernstein’s most powerful instruments were his mind and voice. Through his educational efforts, including writing several books and creating two major international music festivals, he influenced several generations of young musicians.

He described himself as “possessed” by the concepts and shapes of music, which kept him engaged throughout his life, especially during troubled times, when he was depressed. Triola raises relevant questions that challenged Bernstein, like what’s the role of the artist in society in creating change? How do artists immerse themselves in work while seeking balance in their lives?

A lifelong activist, Bernstein was a fiercely committed humanitarian and one of the most important cultural personalities of the 20th Century. He worked in support of civil rights; protested the Vietnam War; advocated for nuclear disarmament; raised money for HIV/AIDS research; and engaged in international initiatives for human rights and world peace.

Bernstein’s love for Beethoven is demonstrated in the ending of the documentary, showing him conducting Symphony No. 9 in East Berlin as part of the celebration of the Berlin Wall’s fall. To mark that reunification, he rewrote Friedrich Schiller’s text for the “Ode to Pleasure,” substituting the German phrase for “freedom” rather than “pleasure.” The concert was televised live worldwide, on Christmas Day of 1989, less than a year before his death at age 72.