- Interviews

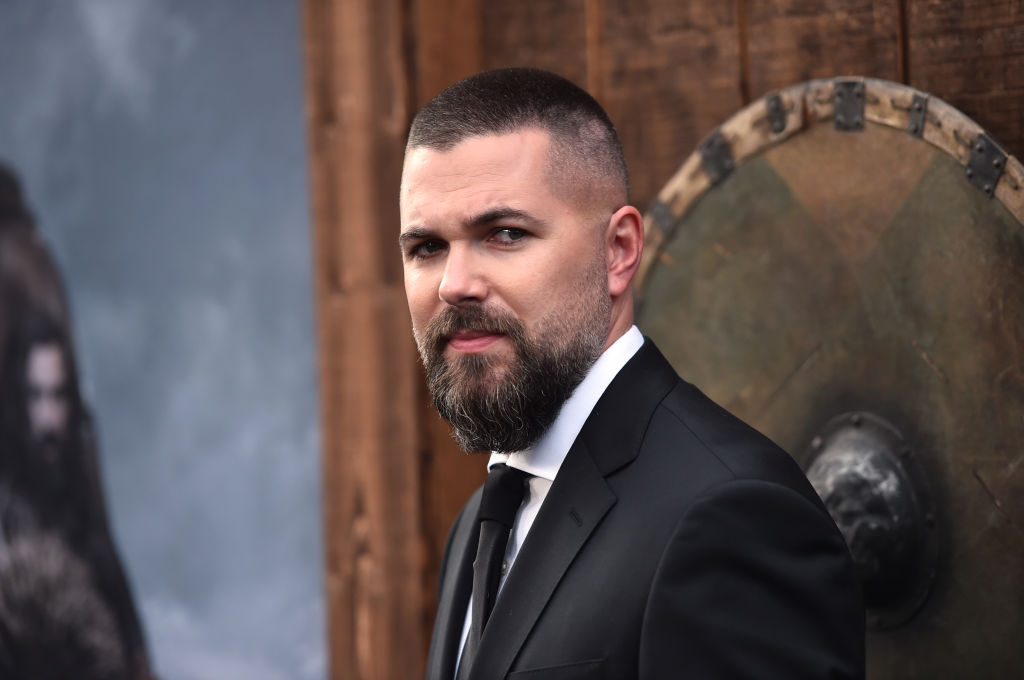

Robert Eggers: “As a kid, I didn’t like macho stuff, except for Conan the Barbarian”

When you sit down to watch a Robert Eggers movie, you know you are in for a history lesson. But far from being a dry, dusty university lecture, Eggers’ films have a perfectly calibrated vibrancy. Watching them makes it easy to feel like you’re watching something filmed a hundred, four hundred, a thousand years ago.

Eggers’ new film, The Northman, stars Alexander Skarsgård as Amleth, the son of a Scandinavian king (Ethan Hawke) assassinated by his brother (Claes Bang), who escapes from his bloodthirsty uncle, later to become a berserker warrior and travels to Iceland in search of revenge.

In the bloody, action-packed film, the director does not spare on historical accuracy, infusing the film with hundreds of years of lore and superstition. The characters recite long monologues about the Norns (gods) who see destiny, the family tree of the Kings, and the shield-bearing Valkyries who lead brave soldiers across the sky to heavenly Valhöll.

Eggers, who was born in New York in 1983, talks about his vision of The Northman in a Q and A following the film’s screening at the Aero Theatre.

Can you tell us about the meticulous research you do in your stories?

Yeah, I like to research. Historical accuracy does not matter at all in telling a story or making a good film but it’s something that is important to me for whatever reason. It’s what excites me. And one thing that is nice about it is that I don’t have to think about what chair or what sword I can create out of my imagination is going to best represent the character and their internal state and who they are. I can just look at archeological evidence of chairs and swords and say, “Make that one.” Then we can accumulate a lot more details to make the atmosphere richer quicker. And that’s a good thing but I had the great privilege to be working with the greatest Viking historians and archeologists in the field.

Neil Price is with us tonight, everyone. We had a lot of men and women who we could ask. And this stuff happened a thousand years ago so there certainly are holes and there are things we don’t know. But if you have a manuscript with a hole in it, you don’t just use ad-libs to figure out whatever word you might want. You look at all the words around it to try to figure out what that missing word would be. So even the things that we were having to “create” were still based on the research.

Do you research and then write the script based on some of those discoveries?

I usually do about a month of research, and then I start writing. And I know that I’m going to have to rewrite and change stuff because I don’t know everything. But I get a bunch of ideas, a bunch of images. I know I want to have a naked sword fighter on a volcano. I know I want to have a severed head preserved in herbs that can talk, and then you start going. But then it can be hard because you can have a scene or a moment that you really like, and then you learn that it’s just not historically accurate.

And again, you could just stick with that, and that would be totally fine. There’s this film, Becket, from 1964 based on a French play, which makes Becket a Saxon. And he was a Norman. The whole thing about him being a Saxon, and it’s a great story but it’s just not true. But it doesn’t matter. It’s a great film but that’s just not how I like to work.

What was your attraction to the Vikings?

Growing up, I didn’t like Vikings. I was a weird, sensitive kid who was beaten up for wearing costumes to school. I didn’t like macho stuff, except for Conan the Barbarian. Then, as an adult, the misappropriation of Viking culture by the Nazis and the Right made me uninterested in Vikings. But then, I went to Iceland. It is nothing new to say that Icelandic landscapes are incredible. They were my inspiration.

It made me think of people who sailed through there in the so-called Dark Ages and didn’t die. I would like to know more about it. So, I picked up the sagas and got into Viking culture.

Then two years later, Alexander Skarsgård and I had lunch. He has been interested in Vikings since he was a kid. I learned that he’s been trying to make a Viking movie for ten years with my friend Lars Knudsen, one of the producers of The Witch. I said, “Well, I’d like to be a part of that.” We tried and that’s how it started.

Can you talk about the fight scenes? Rarely do you see scenes that seem so natural.

It’s tough for me because I’m trying to make an action tent pole movie, to eat popcorn with and enjoy it. But it is a culture that celebrates violence. So there are times when the violence needs to be thrilling but also, I don’t want to be condoning or glorifying violence. And it’s a difficult line to walk. I don’t have an answer. These are the kinds of questions that my colleagues and I asked ourselves while we were making the film. Because sometimes brutality is there not to be hardcore but to remind us that the world is screwed.

My hope is that by making a movie of this scope and saying things like this out loud, the audience will react and say, “This is amazing.” And maybe at the same time, feel guilty for feeling that.

What is your relationship with the actors? How do you work with them? Do you let them go their own way? Do you talk to them before you start shooting?

I prefer doing to talking. I think that sometimes you do need to talk stuff out but I like to just get going. In the world of theater, there’s this thing called table work, where you learn tabling, where you spend weeks sitting around a table talking about shit.

I prefer to just start rehearsing and getting into it. I’m looking for actors who like to make strong choices and who are willing to be vulnerable and show no fear and have good faces.

Was it difficult to get Bjork for the film?

Robin, one of the composers, had worked with Bjork a lot and they were friends. So, he introduced my wife and me to Bjork. She introduced me to Sjon, the co-writer. They have known each other since they were teenagers when they were like Icelandic punks. And so, it was basically, a familial environment for her.

How do you develop visual language? Do you do a storyboard?

I have a kind of bad habit of some scenes I really see cinematically but some scenes I’m just kind of writing as a story. And I think that was even more so the case working with Sjon because he’s a novelist and a poet. And while he’s incredibly cinema literate, he’s a novelist and poet. So, I think that a lot of times when I’m writing, even though it’s the complete antithesis of everything that I like about filmmaking, I’m kind of picturing bad TV coverage when I’m writing. Truly, it’s embarrassing to say but it’s true. And so, then once I’m working with Jarin, then it’s kind of a new phase in the writing process. And a lot of times, we’re condensing beats and actually rewriting and reordering the scenes so that we can capture it in one long take. And realizing that we have to put more edits if it was exactly as written. So, we’re actually rewriting as we’re shot listing and then storyboarding to make something that is more consolidated, precise, and streamlined.

Translation by Mario Amaya