- Film

Docs: “Waterman” Celebrates Native Hawaiian Olympian, Father of All Board Sports

Pacific Islander Duke Paoa Kahanamoku was a four-time Olympic swimmer who picked up three gold and two silver medals, and just happened to almost single-handedly internationalize surfing — an effort whose planted seeds would then go on to flower into every other board sport in the world, from skateboarding to snowboarding.

The first person to be inducted into both the Swimming Hall of Fame and Surfing Hall of Fame, Kahanamoku also broke through racial barriers many years before icons like Joe Louis, Jesse Owens, and Jackie Robinson. For some reason, however, he isn’t as lauded or remembered as those figures.

The new documentary Waterman, narrated by Jason Momoa and (after a brief theatrical run) now streaming on PBS as part of its “American Masters” series, aims to rectify that unfortunate anonymity, and shine a deserving light on a humble and taciturn man. Directed by Isaac Halasima, the engaging film strikes an affecting and informative balance between chronicling some of the disheartening ways in which its subject was taken advantage of, and held as a prisoner of his time, and honoring the unique blend of incredible talent, unshakeable optimism and gentleness of spirit which helped make him such a beloved and revered figure.

Halasima’s film takes its title from a biography of Kahanamoku by David Davis, which offers a nod to the honorific bestowed upon Hawaiians who have mastered various tradecraft of their oceanic borders. Blending together all sorts of rare archival material with contemporary footage, the documentary breathes life into its subject’s rise to fame and shows how he became the public face of a changing Hawaii, as it evolved from an isolated and largely unknown island kingdom into a destination vacation spot for American travelers.

Born in Honolulu in 1890, three years before the overthrow of the Hawaiian kingdom, Kahanamoku’s path to medal-winning glory is a story unrivaled in the history of the Olympic games. Pulled into an amateur athletic showcase event in Hawaii in August 1911 merely as a local lane filler in an outdoor salt-water swim, Kahanamoku obliterated the competition, shaving nearly five full seconds off the 100-yard freestyle world record. Mainland officials, however, doubted the veracity of the time — some even said the quiet part out loud, noting that there was surely no way a “colored boy” could achieve such a feat.

A full century before the advent of internet-crowdsourced fundraising, Hawaiians of all economic stations pitched in to raise enough money to send Kahanamoku to the Olympic trials in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. After struggling during his first-ever swim in a pool, and navigating some additional setbacks, Kahanamoku would eventually both qualify for the United States swim team for the 1912 Olympics and go on to best favored Australian Cecil Healy in the 100-meter freestyle. His self-taught double-flutter kick and streamlined stroke would later be picked up and mastered by future generations of swimming legends, including Michael Phelps.

However, both because he lived in a time before Olympic athletes were permitted to have corporate sponsorships and because various power brokers in Hawaii forced him to retain his amateur status in order to continue to use him as an ambassador, Kahanamoku found himself in the odd and difficult position of not being able to make money swimming. Between Olympics he would work odd jobs, including as a cabana boy, giving surfing lessons to wealthy divorcees and other tourists.

In fact, traveling to Australia in 1914 at the invitation of Healy, Kahanamoku would craft his own board and dazzle audiences with his surfing showmanship, including headstands and pipeline curls. This trip planted the seeds of a rabid surf culture in Australia, and in subsequent years Kahanamoku’s easygoing celebrity had kids all over the world trying to emulate his moves with their parents’ ironing boards.

In the pool, Kahanamoku would eventually be unseated by rival Johnny Weissmuller, with whom, characteristically, he still enjoyed a good personal relationship. Following the 1924 Olympics, Kahanamoku began dabbling in Hollywood, appearing in movies like 1927’s The Isle of Sunken Gold and 1930’s Girl of the Port.

The rest of Kahanamoku’s post-Olympics life (he would compete one last time in the Olympics in 1932, making the water polo squad as a back-up member) isn’t tragic per se, but it is melancholic. Its trajectory reflects the severe social limitations of the era in which he lived. While he had both years of experience and a preternatural screen presence, Kahanamoku couldn’t get Hollywood studios to give him a shot at leading man roles and had to watch Weissmuller land the part of Tarzan and go on to become a big screen star. Kahanamoku would be elected (and re-elected for 12 additional terms) to the position of sheriff of Honolulu, a somewhat ceremonial endowment.

Waterman tells an interesting story, but also does so with an aplomb that matches its subject. The movie’s estimable slate of interviewees includes surfing legends Fred Hemmings, Laird Hamilton, Kelly Slater, and Carissa Moore, but also playwright Moses Goods, musician Jack Johnson, and several authors, including the aforementioned Davis. Their variety and different points-of-view help paint a portrait of Kahanamoku as a man and member of his community rather than just an athlete.

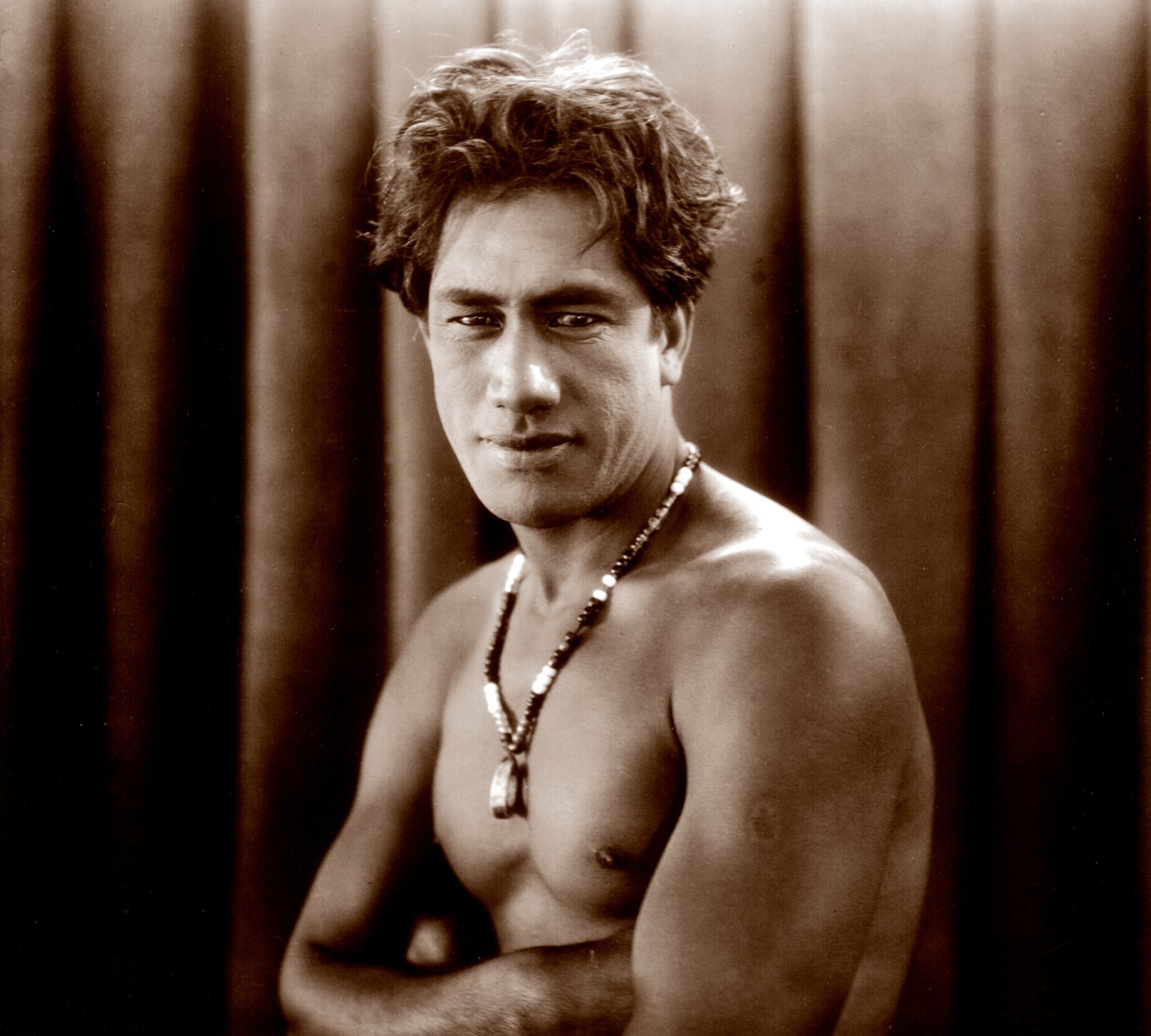

Reenactments in nonfiction films can be a sign of enfeebled imagination or a dearth of other material, but in Waterman they’re very well done, and threaded throughout the movie just right. The actor Halasima casts, Duane DeSoto, both bears a striking resemblance to a young Kahanamoku and is highly expressive and engaging on his own.

Finally, Halasima also chooses the perfect framing device for his film — a February 1957 episode of This Is Your Life, a TV show in which honorees were brought to Hollywood under various pretenses and then surprised by host Ralph Edwards with a sort of guided tour, replete with guests and in front of a live studio audience, of some of their most notable achievements. Some of this footage is, of course, inherently poignant. The way Halasima and his team then intercut and tie it back in with interviewee recollections, though, creates further viewer connection.

One moment is uniquely humanizing and a bit funny, as a former Olympic teammate chides a shrugging Kahanamoku over his ability to grab naps anywhere and anytime, no matter the pressure of an impending competition. The biggest scene serves as one of the most significant emotional pillars of the film: Kahanamoku’s incredible rescue, one by one, of eight people from a capsized boat off the coast of Newport Beach, California, in 1925. After he saved as many as he could, Kahanamoku paddled back out to bring dead bodies to shore, and, overwhelmed, then hid while friends told the story of the rescue to authorities.

When he passed away from a heart attack in 1968, Kahanamoku’s funeral service on Waikiki Beach drew an estimated 10,000 people. In 2021, surfing made its Olympic debut, finally fulfilling his lifelong dream. In the years in between, though, the continued reverberations of Kahanamoku’s giving, selfless spirit serves as a rich embodiment of a single Hawaiian word in which lives an entire world: aloha. It can mean both hello and goodbye, yes, but also love, and the spirit that you share with the world. Waterman shows that few did it as generously as Kahanamoku.