- Film

10 Films About the Death of Planet Earth

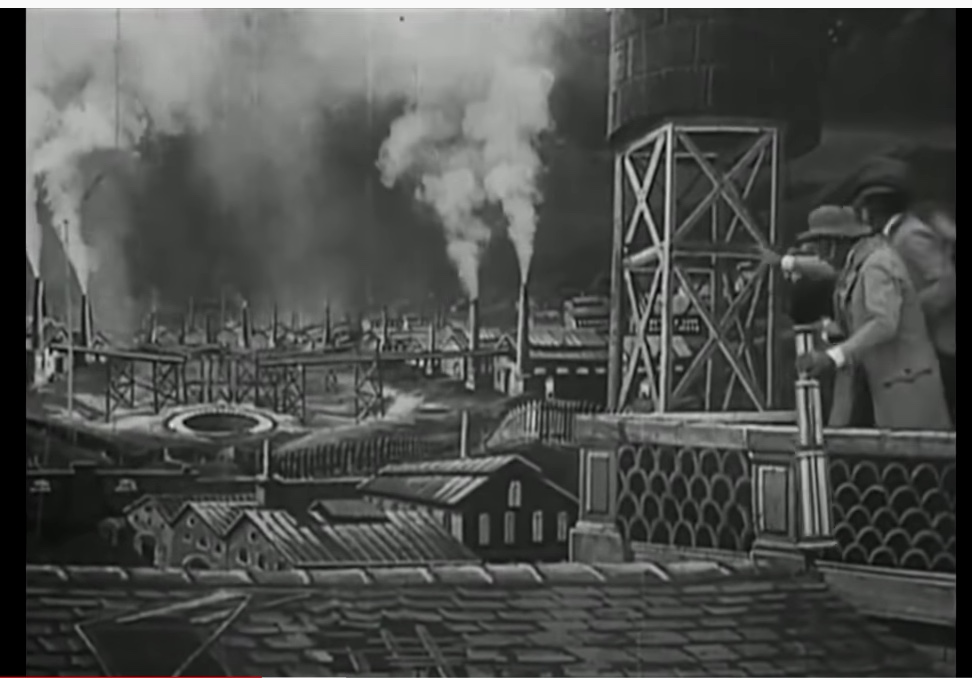

Movie enthusiasts probably had seen George Méliès’ A Trip to the Moon (Un voyage dans la lune) many times. It’s fun, beautiful, energetic, and full of complex special effects – an extraordinary picture for 1902. There is, however, a scene right in the first act that we, the audience, tend to forget: the moment when the scientists are dragged outside their hall to see why they must support a trip to the Moon. The reason for the journey is spelled in that brief but powerful moment: they are shown a once beautiful city covered in smoke and ashes, suffocating in a thick shroud spelled from a profusion of furnaces.

That moment is a glimpse of the Second Industrial Revolution rushing into the 20th century with an enthusiasm that, by the time movies can be played in the comfort of our homes, our air, outside, is very similar to Méliès’ dystopia.

Moving pictures themselves were a key part of this new dawn of human intelligence, and it’s very interesting that, sometimes, among comedies, dramas, and adventures, films like Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, in 1927, and Richard Lyford’s As the Earth Turns, in 1938 foresee a strange, exhausted Earth. The hungry masses and frenzy cities of Metropolis, and the possibility of controlling weather as a political gesture in As the Earth Turns, were way ahead of our very real fears in the first decades of the 21st century.

The visual journey of the evolution of our assault on our planet has been told in a variety of movies from all over the world. These are a few of these meditations on what has happened, what can happen, and what comes next.

Planet of the Apes, dir. Franklin J. Schaffner, 1968

Of all the adventures and misadventures of Charlton Heston and his companions in this huge blockbuster, the most expressive moment is the very end. There it is, the film says: did we ever bother to hold on to our planet? Based on French author’s 1963 novel “La Planète des singes” -which in turn was based on Jonathan Swift’s “Gulliver’s Travels” – Schaffner’s movie became the core on a never-ending franchise, with five sequels, a TV series, animated series and, in the next second, remakes that go from Tim Burton’s in 2001 and, in 2011, 2014 and 2017, directed by Rupert Wyatt and Matt Reeves.

Also: The Day the Earth Stood Still, dir. Robert Wise, 1951

Silent Running, dir. Douglas Trumbull, 1972

Sometime in the 21st century, all plants have died on Earth. A few samples have been sent to a series of space greenhouses outside the orbit of Saturn, in a desperate gesture in the hope that, one day, reforest the planet. But when the resident botanist (Bruce Dern) receives orders to terminate all greenhouses – too expensive for Earth humans of the future- things get wild. Fresh from the challenges of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, the special-effects creator tested his director skills. Backed by the enthusiasm of Universal Pictures, determined to produce movies for the culturally and politically critical post-war generation, Trumbull used all his expertise to create the space greenhouses in a decommissioned aircraft carrier docked in Long Beach, California.

Also: Soylent Green, dir. Richard Fleischer, 1973

Blade Runner, dir. Ridley Scott, 1982

The atmosphere is extraordinary (thanks to Douglas Trumbull, back to special effects), the narrative is tense and dark (from Philip K. Dick’s 1968 novel “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?”), and the performances are strong. But, back in 1982, the studio, critics, and audiences turned their back to what, in the future, would be one of Ridley Scott’s masterpieces. Could it be the fear of a 2019 Los Angeles immersed in a perpetual night, with the rich living above the clouds and the smog, and everybody else soaking in acid rain? Are we close, now, to cities as sick as this imaginary Los Angeles?

Also: Blade Runner 2049, 2017

12 Monkeys, dir. Terry Gilliam, 1995

Inspired by Chris Marker’s legendary 1962 short film La Jetée, Terry Gilliam brings up one of the most terrifying possibilities of a world out of balance: the pest. Playing with past and future – and with Brad Pitt and Bruce Willis in the cast – he shows how easy a virus can upend everything humans had built. At the time, the notion of, finally, having the AIDS epidemic under control made the thriller a fantastic take on viruses being a terminal risk to the Earth’s population. 27 years later, though…

Also: Interstellar, dir. Christopher Nolan, 2014

Princess Mononoke, dir. Hayao Miyazaki, 1997

Inspired by traditional Japanese legends, Miyazaki went back to the Muromachi period of Japan’s history ( between the 14th and the 16th centuries) to weave a cautionary tale: a young warrior and a mysterious young woman join forces to protect the forests and those who live therein, against the greed of a wicked rich lady, determined to make war and reign supreme. Gorgeously drawn, the “once upon a time” tale clearly becomes a fable about the perils of abusing nature.

Also: Wall-E, dir. Andrew Stanton, 2008

Children of Men, dir. Alfonso Cuarón , 2006

While many dystopian pictures focus on the destruction of the environment, Cuarón takes P. D. James’ novel to illustrate how a more profound danger can undo centuries of life on Earth. Set not far from where we are – 2027 – Cuarón’s world is a planet of desperate sterile people, unable to have children, the human population diisappearing from the face of the world. This deep unbalance – social, political, environmental – leads to a world crumbling in front of our eyes. It’s thrilling and scary and, in the end, beautiful.

Also: The Road, dir. John Hillcoat, 2009

Contagion, dir. Steven Soderbergh, 2011

A mere nine years before a real pandemic, Soderbergh pushes onward the idea already developed by Gillian, Cuarón, Petersen – the virus, this tiny creature we pay no attention to until it jumps into our unbalanced world and destroys everything. The scariest element of this bio-thriller is that all scientific elements have been checked by real biologists and doctors – just like we had experienced in the last two years.

Also: Outbreak, dir. Wolfgang Petersen, 1995

Beasts of the Southern Wild, dir. Behn Zeitlin, 2012

Zeitlin’s fantastic tone leads us to follow the six-year-old heroine Hushpuppy (Quvenzhané Wallis) into a magical place. In the background, however, there’s the narrative’s major foundation: a world overtaken by water, the result of rising sea levels. Isolated cabins, shacks, and even the community schoolhouse are surrounded by mounting water, and the children learn to swim and master nautical skills. Hushpuppy’s village is called “Bathtub”, and the weather gets worse, quickly. Zeitlin’s vision embraces the children’s courage. The adults’ heritage, he points out, is heartbreaking.

Also: Waterworld, dir. Kevin Costner, 1995

Snowpiercer, dir. Bong Joon-ho, 2013

Based on the graphic novel “Le Transperceneige”, by Jacques Lob, Benjamin Legrand, and Jean-Marc Rochette, Bong explores what happens when a whole society is compressed in close quarters, with no way out. The world had become a prison, covered in ice, thanks to centuries of humanity’s hubris – the Earth has congealed thanks to a catastrophic effort to reverse global warming. Humans survived the first Ice Age. Can they do the same, imprisoned in a train?

Also: The Day After Tomorrow, dir. Roland Emmerich, 2004

Don’t Look Up, dir. Adam McKay, 2021

Besides our seemingly never-ending efforts to explore and destroy our rich environment in the name of “progress” there is always the risk of a meteor. Tiny, blue, and beautiful, Earth is, as much as we know, the solitary home for our species, alone in space. Space has its perils, McKay points out, but our tendency to ignore, distort, lie and try to take advantage in dire moments someday will exterminate us all. The cast is top-notch, we laugh a lot, but that’s the painful truth.

Also: Deep Impact, dir. Mimi Leder, 1998