- Film

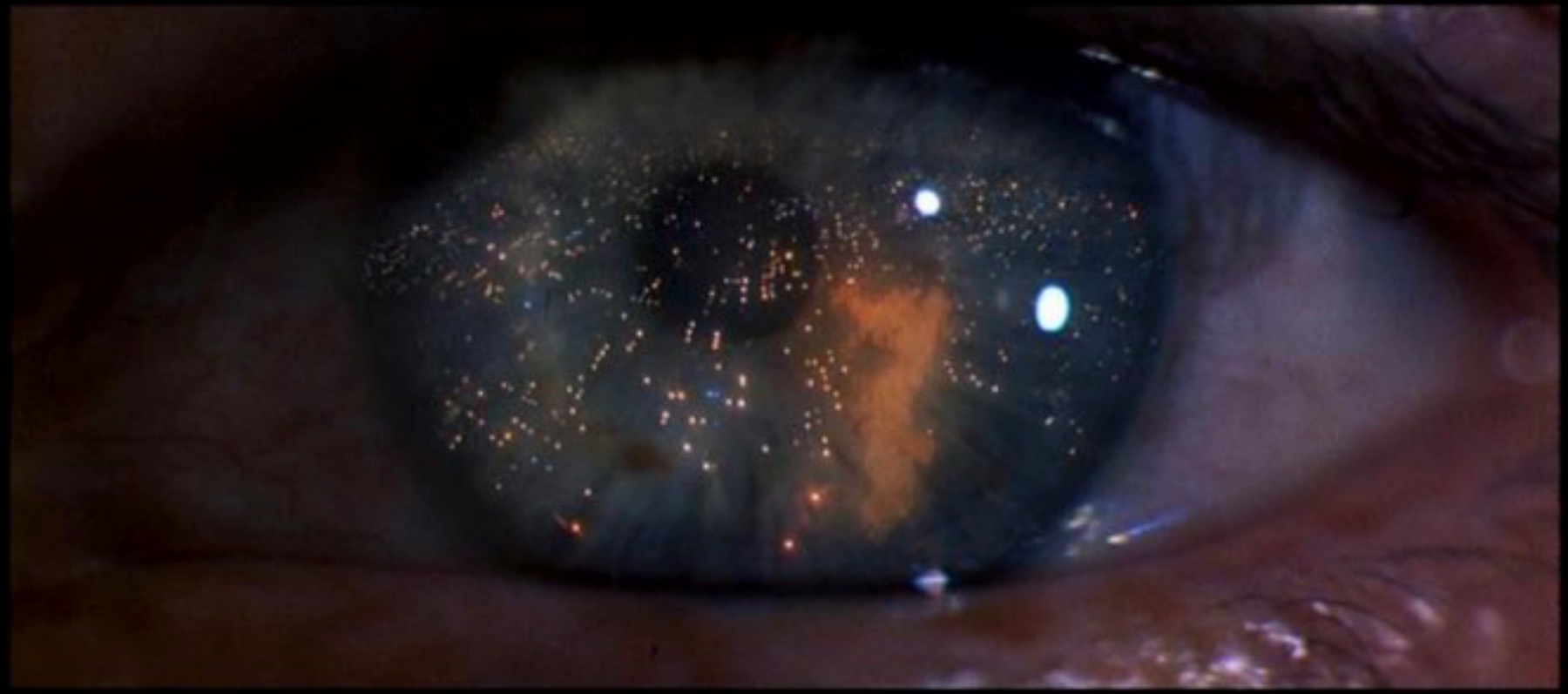

40 Years Later, “Blade Runner” Is Still Unforgettable

Blade Runner (1982), directed by Golden Globe nominee Ridley Scott, has been with us for four decades. The opportunity to revisit Blade Runner via streaming or in its various available versions, including Blu-Ray, is a chance to retell the story of the protagonists behind the making of the film, considered by many as the best of its kind.

The first to figure in how Blade Runner got to be made was the screenwriter Hampton Fancher, whose mother was Mexican-Danish while his father was British-American. After growing up on the east side of Los Angeles, Fancher fled to Spain at the age of 15 to become a flamenco dancer.

Returning to California, Fancher starred in more than 50 film and television projects, becoming romantically involved with actresses such as Barbara Hershey and Teri Garr.

But it was the Philip K. Dick novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968), that really stole Fancher’s heart, fueling his desire to adapt the story for the screen as far back as 1975.

Dick was suspicious that Hollywood producers were only interested in creating spectacular scenes and wanted to turn his novel of existential questions and characters that define his humanity and childhood memories into a crass hunt for androids by futuristic policemen.

However, Fancher’s script did get Dick’s approval, and his alliance with producer Michael Deeley, as well as Alan Ladd Jr. and his film company, made Dangerous Days, as the screenplay was titled then, stand a chance of seeing the light.

Star Wars: Episode IV- A New Hope by George Lucas helped pave the way for science fiction in 1977. Ridley Scott further sparked the genre with the premiere of his Alien (1979). The director was already on board the film adaptation of the novel Dune, dreaming of making his own galactic saga.

But the death from cancer of his brother Frank Scott in 1980 made the filmmaker turn to something more somber and existential like Dick’s story.

Throughout the script of Fancher, who would later be joined by David Webb Peoples in collaborating on the screenplay, the protagonist Rick Deckard had to hunt down a handful of androids, known in this dystopian universe as “replicants,” whose mission was to prevent their synthetic bodies and artificial intelligence from expiring after four years, condemning them to their termination or death.

The now retitled Blade Runner script would transport the audience to 2019 Los Angeles, with a cyber corporation called Tyrell with the motto of “more human than human.” It brought references from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein to Nietzsche’s nihilism, giving equal space for humanism and the creation of the new cyberpunk culture by putting man and machine at the same table, and even on the same bed.

In the casting of Harrison Ford, the Star Wars saga’s cynical pirate Han Solo, he brought Deckard the halo of 1930s and 1940s noir stars like Humphrey Bogart and Robert Mitchum, Rob the latter a Fancher favorite.

As Scott enjoyed doing in his career, he dedicated himself not only to directing a script but also to creating a world on the screen.

He invited Douglas Trumbull, a veteran of 2001: A Space Odyssey and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, to do the special effects, called the musician Vangelis (who would be nominated for a Golden Globe for his score on this film) and made his ally Lawrence G. Paull as his production designer to help him make 21st century Los Angeles.

Paull worked with an obsessed Scott, who wanted the stages built at the Warner Brothers studios in Burbank. The filmmaker specified that in the studio-shot scenes, it will be raining almost all the time, as well as those lensed on the streets of Los Angeles, which included downtown with its narrow streets, theaters, tunnels, and structures, including the Bradbury Building, built in 1893.

Cars would fly around while building-sized craft would cast beams of trailing lights, always creating backlighting and the feel of a retro-film noir forged with cinematographer Jordan Cronenweth.

The strong female presence, characteristic of Scott’s cinema, brought Daryl Hannah and Joanna Cassidy as the replicants Pris and Zhora, respectively, while newcomer Sean Young as Rachael, the femme fatale android with whom Deckard would fall in love.

The Latino Edward James Olmos would be the policeman Gaff who deals the necessary blow to Deckard to help him see what is evident in front of him.

But one part of the story’s heart happens on the ledge of the Bradbury when the replicant leader named Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer), like a modern Prometheus, spares Deckard’s life to tell him in his goodbye – in a speech improvised a bit by the actor – that his memories will be lost with him, “like tears in the rain.”

Although the box office reception was a disappointment to the Blade Runner producers, in addition to the devastating reviews after its premiere on June 25, 1982, the film was eventually appreciated by film buffs and academics, scientists, and defenders of cinema as art, citing Scott’s film as an example over and over again.

The legacy of Blade Runner persists. It’s impossible to quantify the film’s influence like those many raindrops on Roy. In the middle of 2022, when there is talk of the definitive transition from cinema to other ways of movie exhibition, the film that deals with how machines want to continue existing among us, becomes the perfect metaphor for how the art of the past insists on staying with us, helping to define our humanity.

Translated by Mario Amaya