- Industry

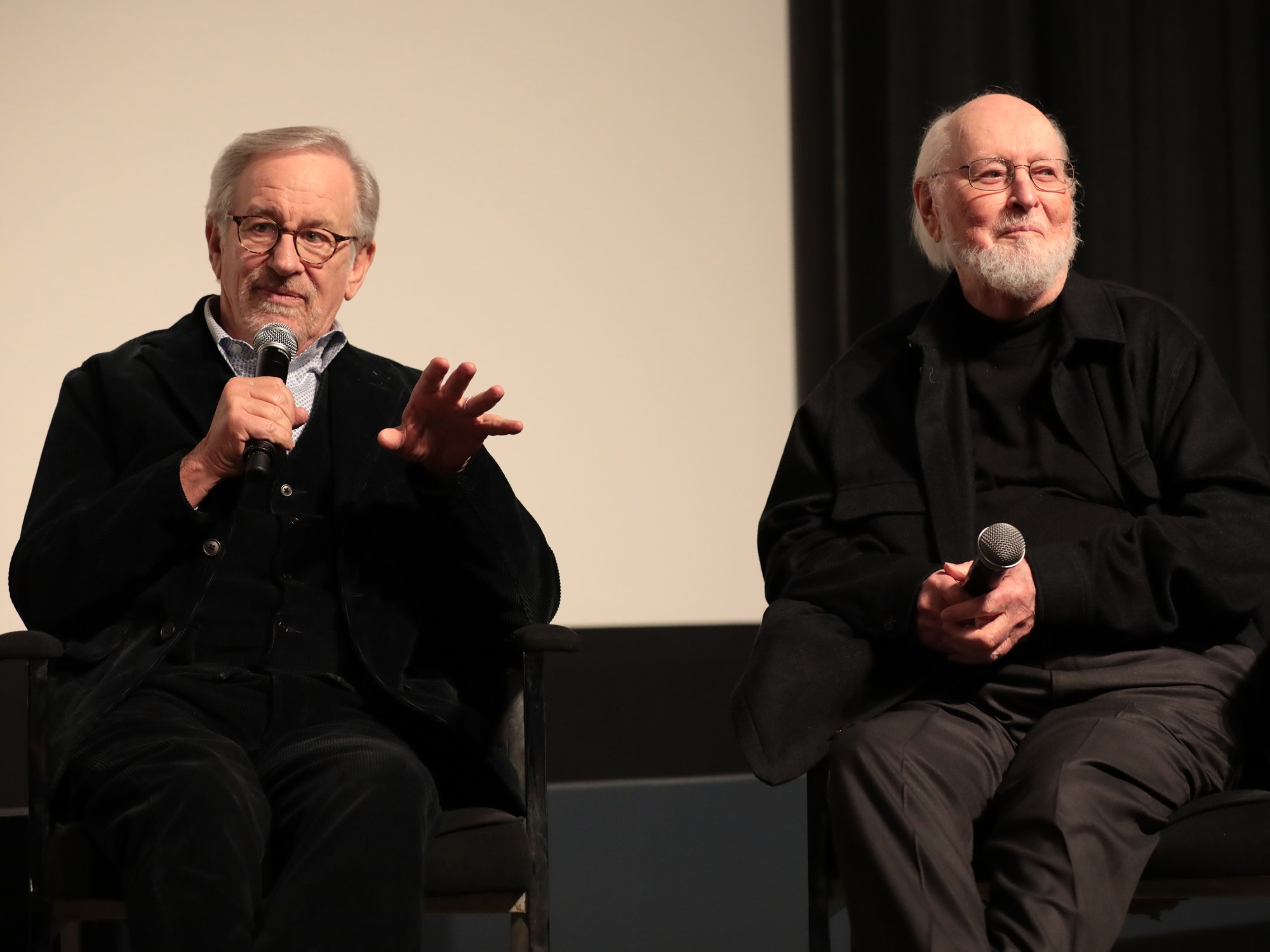

50 Years of Cinema and Music: A Conversation with Steven Spielberg and John Williams

A long time ago, a young filmmaker ready to shoot his first full feature – after six TV shows and three TV movies – was listening to his favorite scores when one caught his attention. The album was the soundtrack of The Reivers, directed by Mark Rydell and with a score by John Williams.

“And that was the first time I actually laid ears on John Williams,” recalled Steven Spielberg, then a young filmmaker, and now sharing the stage with John Williams at the Writers Guild of America Theater in Beverly Hills. The “In Conversation with…” was organized by the American Cinematheque on a cold and rainy night last week. “That was it. That was the very first time. And I really made a vow to myself.”

The year was 1973 when Williams was called by one of the Universal senior executives who suggested that he should meet this rising filmmaker on his first major project. “The best way to get together is for you both to have lunch somewhere,” said the exec.

The lunch happened, and it was more than fruitful – from this unforgettable meeting, a successful partnership gave us five decades of movies and music intertwined in a way that only true partners can weave, at the same time bold and delicate.

“This Reivers score that he talked about, he would start singing the main theme, and then the third theme, and the fourth theme, which I’d long since forgotten,” Williams recounted. “And he remembered all of that, adored film music and was almost a scholar, with his level of information about it. So, I was enormously impressed.”

From that first conversation came Spielberg’s first feature film scored by Williams, with Toots Thielemans as the soloist – The Sugarland Express in 1974.

One year later, the whole world would understand the power of a thump-thump-thump that will never leave our minds. “It seemed to me a good idea on several levels that you could play it very slowly…or very quickly…or soft or loud,” Williams reminisced. “And so, we could manipulate the impression of an audience if you saw anything but just water.”

It was, of course, Williams’ iconic score for Jaws. Spielberg said to Williams, laughing: “I was scared when you first played it for me on the piano because after you finished playing the ‘da-da-da’ on the piano, you looked up at me and you were smiling. I started laughing because I thought…I didn’t know you that well, I thought you were pulling my leg. And John said, ‘No, this is serious,’ and everything like that. But I was very lucky because God knows the shark never worked but Johnny did.”

It’s all true: “Bruce” – the name of the mechanical Great White Shark who could barely move – was more of a problem than a solution but Williams’ simple, precise and scary theme music will never leave the minds of the millions of Jaws fans.

From the ocean to the universe, Spielberg challenged Williams with Close Encounters of the Third Kind and E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. Spielberg explained, “When I was trying to figure out how to make a UFO movie, I had one concept – I want to make a movie about a UFO and Watergate because remember, that was all the rage then when I was writing this thing.

“I went ahead and wrote the ending of Close Encounters first before I had any of the characters. I wrote the end first. And in writing the end, I was trying to figure out where they’re going to come out of the ship…I didn’t call it the mothership then. It was just a large ship. When they came out of the ship, were they going to suddenly talk telepathically?”

Williams had the answer: music can express what inter-galactical words couldn’t say. The visitors from other galaxies could share ideas with humans in the glorious ending of Close Encounters, when the mothership sings in a common language, with the help of a tuba and synthesizers.

Williams said, “It’s a kind of unbelievable musically, linguistically but kind of a loop. We were not thinking of that when we chose this. This is just a kind of rationalization of why this is special.”

Spielberg explained, citing Harrison Ford’s scene in Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark when he finally finds the Ark, when the duo went back to the stars: “This is the only time where there is a material contribution to the drama and almost the religious drama of the sequence based on how the music starts very simply and then gets mysterious.”

“ I think E.T. is maybe Steven’s masterpiece,” said Williams. “It’s almost a perfect film. Really.”

Moving through the end of the 20th century with three films focused on the Second World War – Empire of the Sun, Saving Private Ryan and Schindler’s List – Spielberg and Williams analyzed the relationship they developed over their fifty years of creativity and friendship.

“The first thing I always do is I offer John the script, intending to direct,” said Spielberg. “And 80 percent of the time, John prefers not to read the script (laughter) because it’s an abstraction in a sense. I mean, he’ll certainly understand the story and the storytelling. He obviously has an idea what the story is but it’s when he sees the film for the first time, then he can start the writing.

“He can just start dreaming and thinking, what was this going to sound like, how can I…what John does for me is, I tell a story and then John retells the story musically. It is a second musical script on top of the first script that I shoot from.”

A selection of scenes from Jurassic Park and Lincoln focused on the power of music as a language.

In Jurassic Park, Spielberg said, “Dinosaurs, especially the brachiosaur in this sequence, wasn’t even in the cut when John saw it. Everybody’s looking up at nothing. We had a large wire connected to a truck. At the top of a tree, we pulled the wire as if the brachiosaur was eating from the uppermost branches. I remember this very well, when John first saw the picture, he talked about the nobility of these animals.”

For a quiet and somber scene as Lincoln traverses a battlefield covered by bodies and blood, Spielberg wanted a strong presence of silence, without words. Williams concurred. “It occurs to me looking at these films to think instead how powerful Steven has been on the subject of war and the suffering involved in it and so on,” Williams said. “He captures the pain and the tragedy so effectively, so deeply, I think.”

All these years and all this work had made them more than partners and friends – they are the pieces that they created.

“A lot of it I do and play,” Williams shared. “Fifty years together is a long time and with him, it’s like a perfect marriage. I put it in that frame because he’s so dear. Thousands of ideas and themes I’ve presented to him on the piano, and he’s never said, ‘That’s lousy’ (laughter) or ‘I don’t like it.’ It’s true. He will say, ‘Let’s try something else.’ ”

And in the end, the two old friends shared something nobody had heard yet. Back in that first meeting in a fancy Beverly Hills restaurant in 1973, Williams couldn’t find his potential creative collaborator at any table. “A kid was sitting there,” Williams recalled. “He looked to be about 17 or 18 years old, truly. And I thought, maybe this is Mr. Spielberg’s son.”

Spielberg laughed nonstop. “You really thought I was 17? I was 24! But yes, I had acne. It was the acne.”