- Industry

Asian Cinema (Part 2): Taiwan, Hong Kong and China

Taiwan has been drawn to cinema as an art form since the summer of 1900 when Oshima Inoshi and his projectionist Matu-ura Shozo brought to Taipei and other cities, the dreamy new moving images created by the Lumière brothers, a mere four years after the novelty had been shown to enthralled audiences in Japan and China.

The island, caught between history’s many chapters made of darkness and light, seems to still be looking for its own identity after centuries of dispute between European powers, Tokyo and Beijing. That search has invigorated the local film industry.

After years of colonial subjugation – sometimes reflecting tastes and styles imported from Shanghai, other times reflecting the Japanese perspective where the Taiwanese were seen as commoners willing to obey while working menial jobs – a landmark moment was reached: in 1929, the film Blood Stains was shot with an entirely Taiwanese crew. Released in 1930, it was hugely successful.

In more contemporary times, Taiwanese cinema showed A City of Sadness. Shot in 1989 by master director Hou Hsiao-Hsien, it focuses on one family, the Lin, now experiencing the retreat of the Japanese influence after more than 50 years of occupation.

Set in 1945, when radio transistors were everywhere, Emperor Hirohito had been heard reading his unconditional surrender in a hurried voice. At the home of the Lin’s, family dynamics are in tatters.

Wen, the eldest boy now returning from the war, opens a restaurant called Little Shanghai. He serves local delicacies with a side of political solidarity favoring the mainland. His heart is all for reunification with the regime in Beijing. The other boy, Wen Leung, lost his mind during the war. He now sits half-despondent in a psychiatric ward. When he is released from the facility a life of crime awaits, given that the job market cannot accommodate his trauma. Wen Shun, the third brother, is still missing. Word is, he might be dead somewhere in the Philippines. The youngest of the Lin clan, Wen Ching, is an outcast of sorts. Deaf-mute, he was never allowed to serve in the army and now manages a beautiful photography atelier.

A debilitating problem with communication permeates every relationship, be it within the family, with friends, loves, or with the authorities. Hope for the future is sparse, full of conflict and misunderstandings, underlined by anger, distance, and social disruption. Tony Leung, brilliantly plays the deaf-mute brother. With the help of his bright intelligence, he is the only one who can grasp the intricacies of human relations and the horrendous political situation. The film won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival.

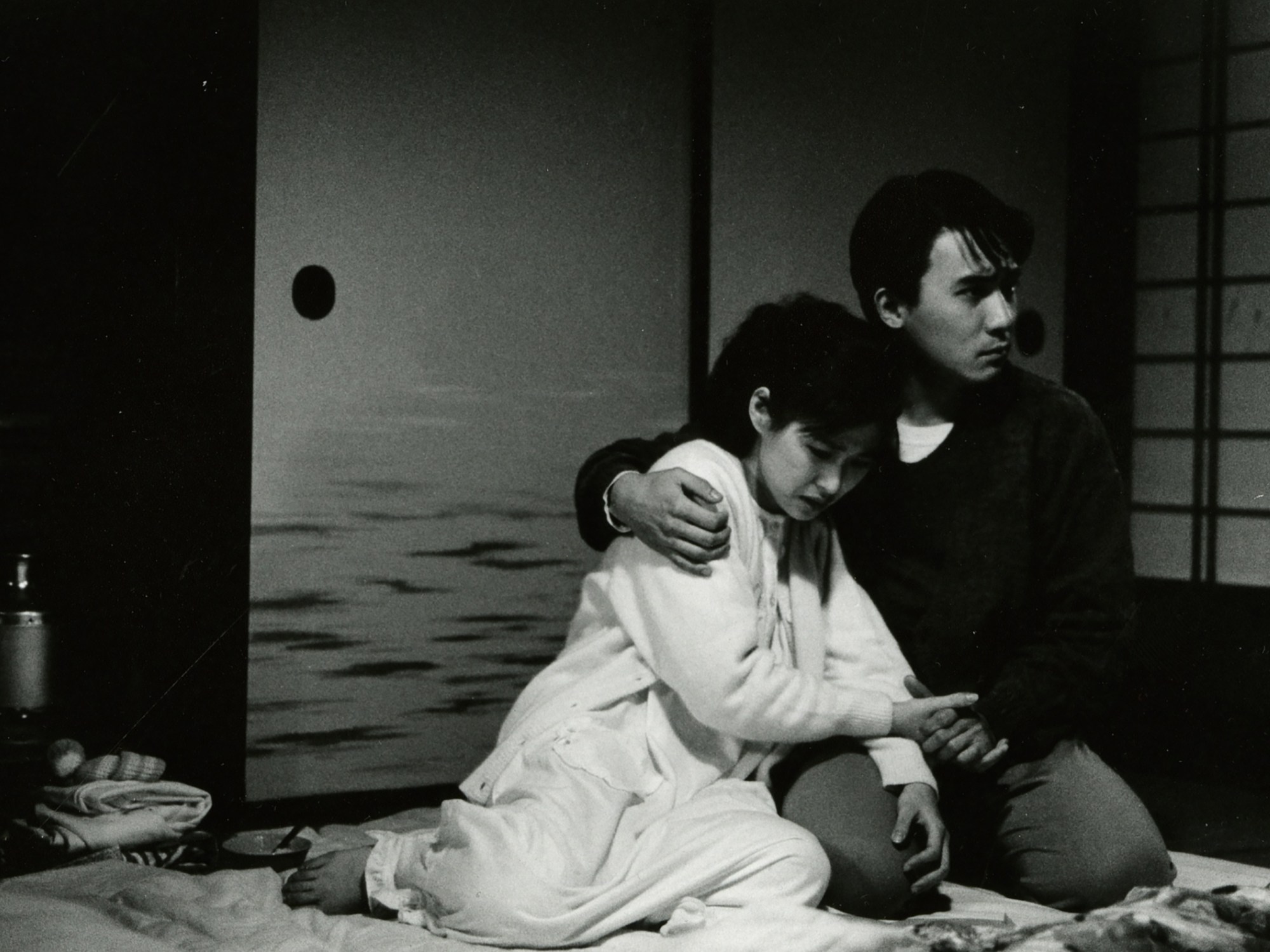

Themes of love, history, and war can also be seen in the work of Golden Globe Winner Ang Lee. From the exceptional Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, released in 2000, to the unforgettable Lust, Caution, released in 2007, Ang Lee infuses the screen with a level of voluptuous artistry that remains unmatched. Fluid, lyrical, tense yet always delicate, never afraid to pair-up vivid acts of sex or revenge with probably the most gorgeous action scenes ever filmed, the Taiwanese director remains one of the most respected and imitated in contemporary cinema. No story is too big. No detail is too small. His control of the medium is a treasure to behold.

A titan in the vast and varied world of cinema world, Hong Kong has always held a special place in the hearts of movie fans. Not just because of Bruce Lee. American writer and director Quentin Tarantino never hid the fact that some of the most surprising and jarring scenes in his 1992 film Reservoir Dogs tapped directly into the in-your-face energy of Hong Kong director Ringo Lam, specifically the smash hit City on Fire. Would Kill Bill I and Kill Bill II exist without the rich legacy of martial arts films choreographed to the hilt in the southern Chinese city? Possibly not.

Influential on every level no matter the genre, Hong Kong’s endless influence can be found in feverish futuristic adventures like The Matrix – almost impossible to imagine without the help of John Woo films – and in more moody, demure art house objects like the Golden Globe Winner Moonlight, an almost direct descendent of Wong Kar-wai’s beautiful work. It’s no surprise that Sofia Coppola mentioned Kar-wai when accepting the Oscar for best screenplay for Lost in Translation.

The Secret, from director Ann Hui, was released in 1979. Here, love and gore go hand and hand. The editing is choppy, like a puzzle, so modern that we still find that template in today’s TV series and theatrical movies. It’s a thriller that reminds us of Hitchcock but the ferocity of the violence shown sends it to another level altogether. Nothing is sacred. A Hong Kong movie can be sweet and panoramic one minute before it descends into a scene featuring a sharp blade and a sensible woman expecting a child.

Style never supplants humanity. And a narrative about ordinary people might include a cleaver as well as spurts of blood going in all directions. Gang-related action movies are sometimes interrupted by cute and sensitive moments that would be more appropriate in a cuddly National Geographic episode. Religious themes are interwoven with carnal instincts and a profound desire for liberation. In Laugh, Clown, Laugh, from 1960, director Li Pingqian throws the audience into profound sadness with the story of an accountant who tries to maintain a dignifying posture while working as a clown during the Japanese homicidal occupation of Tianjin.

In An Amorous Woman of Tang Dynasty, directed by Eddie Fong and released with more than a bit of scandal in 1984, actress Pat Ha plays a priestess who organizes nightly orgies. That’s right. Taoism and radical feminism, all rolled into one. For even more extraordinary visuals, check Empress Wu, a Li Han-hsiang film from 1963. The costume drama fabulousness is not simply operatic and wonderful in every line of dialogue.

Wong Kar-wai’s Happy Together, shown in 1997 was the winner of the Best Director award at the Cannes Film Festival. The story of two Chinese gay lovers takes place in Argentina. Far out, funny and poetic in equal measure, it’s the type of amorous banquet that reminds us of the power of love even when under the most surreal circumstances.

The cinema of China is closely connected to the political trajectory of the nation. It is always dynamic, ambitious, and fascinating, but we’ll always wonder if directors and screenwriters are sharing their own aspirations or if the whole enterprise is an extension of the predominant ideology. Still, there is no denying its gigantic production, and artistry in a new century where movies and gaming and TV and social media seem to feed off one another.

In the 1930s Shanghai was the new Shangri-La of cinema. Relatively insulated from the rest of the country by all sorts of special directives, walls, police controls, and exclusive districts, the city fast became a special zone catering to decadent foreigners and those who had no need to bow to Beijing politicians. Some fantastic works emerged in that decade, helped by beautifully executed productions, lavish sets, and messages of renewal.

Moral ideals such as equality and the civic obligation to fight for a more just society can be found in masterpieces such as The Highway, in 1934, and Street Angel, released to great acclaim in 1937. An untouchable star-like actress Ruan Lingyu, attracted crowds and packed movie theaters in movies like The Goddess and New Woman. Her fame was such that she committed suicide when she was only 24.

Periods of restraint alternated with short stretches of bold creativity. The crackdown on intellectuals prevented innate Chinese creativity to flourish. Still, in times of openness, some wonderful films were made, such as An Unfinished Comedy, in 1957. Social issues were sometimes addressed by movies imported from Hong Kong or Taiwan, as were the cases of Parents Hearts, in 1955, or In The Face of Demolition, in 1953. Social realism and stifled public dissent dominated the dialogue between moviemakers and their audience. Yet, art survived.

A new generation of masters emerged as the country opened up in the 1980s. Magnificent works by Chen Kaige’s Yellow Earth, from 1984; Tian Zhuang Zhuang’s The Horse Thief, in 1986; and Zhang Yimou’s Red Sorghum, in 1987, reminded audiences everywhere of the extraordinary gifts that continue to exist in Chinese cinema. Color, spectacle, symbolism, strength, and grace cut through immense landscapes – geographical, emotional, and historical.

More recently, Golden Globe Nominated Hero, directed by Zhang Yimou and released in 2002, and The Banquet, from 2006, enjoyed huge domestic and international success. Made under the canon of wuxia epics, they mix martial arts, nationalistic fervor, and the richest of productions. Dazzling artistry can be seen in every frame of Farewell My Concubine, which won a Golden Globe in 1993.

For the true cinephile, there will always be Spring in a Small Town, made by Fei Mu in 1948. We first see a house, damaged. The Japanese had just destroyed some of the most idyllic parts of town, of the region, of everybody’s lives. Liyan, the debilitated owner of the house, has no strength left in him to repair the old, crumbling property. His wife, Yuwen, appears more and more distant. One day, a friend arrives. It’s Doctor Zhan. Happiness ensues and the house fills with laughter once again.

What Lyian doesn’t know is that the doctor still nurtures a profound love for Yuwen. His feelings are completely reciprocated. Their affair remained hidden for so long. A solution is found. Maybe Doctor Zhen can marry Yuwen’s younger sister. Now we have four love forces in the house. It is, simply, one of the most beautiful, emotional, and elegant films ever produced in China. The country is for sure filled with treasures of this kind, still hidden away in some state vault.