- Interviews

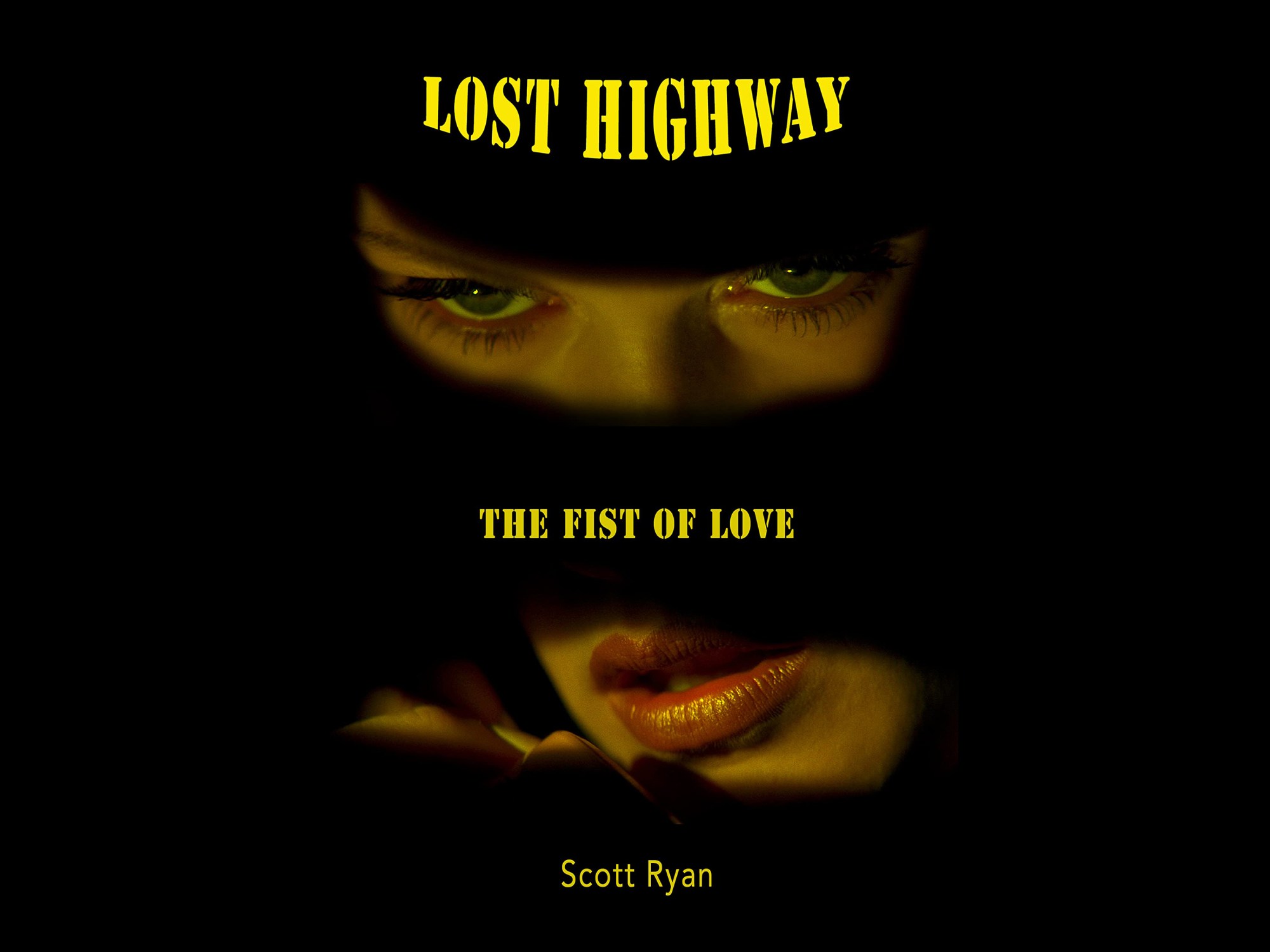

Author Scott Ryan’s “Lost Highway: The Fist of Love” Examines David Lynch’s Most Overlooked Film

David Lynch is regarded as one of the preeminent American cinematic auteurs of his generation. But since Twin Peaks — his surreal television assault on the mainstream zeitgeist, co-created with Mark Frost — debuted in 1990, the arc of his big screen filmography can take on different dimensions.

In his new book “Lost Highway: The Fist of Love,” author Scott Ryan makes an argument that Lynch’s titular 1997 psychological thriller is the director’s most overlooked work. The first of three Lynch films set in and around Los Angeles (it would be followed by Mulholland Dr. in 2001, and Inland Empire in 2006), Lost Highway is split roughly into two halves, and swaps leading men in a manner that confounded a lot of viewers and critics at the time of its release.

The film opens with Fred Madison (Bill Pullman), a saxophonist whose wife Renee (Patricia Arquette) finds a VHS tape on their porch one morning which shows grainy footage of their house. When another tape arrives revealing indoor shots, including some of the couple in bed, they phone the police. The next morning, a third tape shows Fred crouched over Renee’s dismembered body.

Convicted of murder, Fred is sentenced to death row. One day, guards discover him to be missing, somehow replaced by Pete Dayton (Balthazar Getty), a young auto mechanic. When Pete is released from prison and returns to work, he embarks upon an affair with Alice Wakefield (Arquette again), the mistress of a threatening gangster, Mr. Eddy (Robert Loggia). Looming over all this free-floating menace and intrigue is a pale-faced Mystery Man (Robert Blake).

Ryan, whose additional books include “Moonlighting: An Oral History” and last year’s “Fire Walk With Me: Your Laura Disappeared,” recently discussed his new one via Zoom from his Florida home.

A lot of people have this perception of David Lynch as a capital-A artist, singular, doing his own thing, and not caring about the commercial reception. You make the point that the trial of O.J. Simpson dominated mainstream culture, and the soundtrack for Lost Highway is very different from other Lynch soundtracks. Here is Lynch coming off of Twin Peaks, wanting to be popular, perhaps very consciously saying, “This is my big swing.” How do you feel, if at all, that impulse influenced his idea about the narrative he chose to tell?

Well, it was not something I thought about before I started work on the project. You know, a lot of that came from his quote — and (co-screenwriter) Barry Gifford backs it up — that this all came from O.J. I can’t tell you where the idea for Eraserhead came from, but I don’t think it came from a (topic in the) national consciousness, (gripping) 150 million people. But here’s something that does, and it still ends up being his lowest-grossing film.

Then, on the flip side, when I was doing research on the soundtrack, I stumbled upon this quote from someone that said Lynch only wanted popular artists and he was jettisoning anyone who wasn’t popular, because he said this was a pop film. And I was like whoa, I’ve never thought of it that way, and then just like you’re saying, if you put it in the context of his career, he’d gotten eaten alive from basically 1992 until I think personally 1999, with The Straight Story. I wouldn’t say he was forgiven then, that doesn’t really happen until Mulholland Dr. — that’s when Hollywood opens their arms to him and then forevermore, he’s David Lynch.

But in this section of time, he wasn’t this David Lynch that we know today, you know? “Hey, he’s in a Spielberg movie! Of course, he is!” This is not that. And I wanted to put that in context, to say that he was trying to dig himself out of that. To him, he comes up with this idea where he’s like, “Well everyone will love this!” and then… it was too hard for people. Critics and I think even Twin Peaks fans kind of turned their backs on Lost Highway. Not anymore, but in the moment. And I was one of them. I did. I’m not above anyone. I ejected the film (from the VCR when I first watched it), I didn’t finish it.

It’s fascinating as a commentary on following one’s own instincts, and the inevitable intersection between art and commerce. There’s maybe an ironic lesson there for him, and by extension other artists.

Definitely. And I spent some of the intro or chapter one setting this up, because I knew when I was going to make the claim that this is his lost film — it’s Lost Highway, but it’s also lost — that people were going to argue with me. But I thought I set up my argument very well, because I compare it to every Lynch film, and this is the only one where there’s nothing to point to, outside of the soundtrack, which was a huge, huge success, and what he was going for.

What was the most surprising in your interviews with the cast?

Well, from Patricia, it’s how much she remembered the film. I think she’s had the greatest female career in her generation, and if not then she’s in the top three. But I thought, “She’s never even going to remember this film, I’m going to have to set everything up for her.” No. She remembered everything. How she prepared for each character, it was like it was still there. I think it was a traumatic experience for her in a good way — in the good way that trauma can bring art out of you. I think she loved it. And she’s proud of it, she’s glad she did it — but it was hard to do. That, to me, was a surprise.

From Balthazar, the surprise was how much he didn’t care about the Bill Pullman section of the film. But once he said it, it made sense to me. I was like, of course — to him, he’s the star of the picture, he doesn’t care what happened before, and he didn’t even think about it. And I haven’t done it yet, but I honestly want to watch this film where you start where Balthazar joins and watch it from that perspective. Because I thought he was wondering “Oh, how do I play this, how do I match this?” But no, he didn’t even care that Bill Pullman was in the film. That, to me, was shocking (at first).

The film has a love scene in an incredible sandstorm, plus some other interesting and evocative visual effects — none of which are digital. How much going into this project did you want to explore the technical elements of Lost Highway?

Yeah, the thing is that Scott Ressler, who operated the camera, gets more page space than Balthazar or Patrica Arquette. And Bill Pullman’s people kept saying, “We’re going to get you him; we’re going to get you him,” it was six months of almost… so to me Scott Ressler and (cinematographer) Peter Deming are the stars of this book. And, I mean, I love Patrica Arquette and Balthazar and Natasha (Gregson Wagner), but it was the people who captured this (who made it special).

You mentioned the sandstorm, and that’s not an effect — that’s a freaking sandstorm, and it’s still on the 35mm print today. Sabrina (Sutherland) goes through what they had to do to get this 4K restoration (of the movie). Now there is literally still sand on there. And as someone who comes from the ’90s and is right now working on a book about films about the ’90s and studying all this stuff, that’s what matters, man — it’s the 35mm, it’s that they do the effects in-camera. And Peter and Scott both go through lens-whacking. These young kids today, they’re like, “Is that something on FinalCut? Do I click a button for lens-whacking?” No, Scott (Ressler) did it with his hands.

It’s wild. Now there is actually an app that does that.

I know. And they all talk about inventing it right in that room, and you can see it happening. Again, for a film that is totally dismissed and forgotten for 20 to 30 years, the fact that this effect that you see all the time was invented in that film is itself worth capturing.

There are a lot of great anecdotes in the book. For example, that David Lynch would bet money on (finishing shooting at a certain time). I was fascinated with that story from Deepak (Nayar, the film’s producer), because it says something about Lynch’s relationship with those who control pocketbooks, and that he’s very much not living in an artist’s fantasy world, divorced from reality. What was your impression of maybe the hidden meaning of such a story?

That’s a good question. And this is the writer talking, so people can take it as they want to take it, but I think there are multiple hidden-meaning stories in this book. You don’t want to be the writer screaming out on the internet, “I’m telling you, there’s stuff in this book…” (laughs) But I’m telling you, I feel more than any other book, even more than Room to Dream, I think you learn a ton about who David Lynch is in this book, and he’s not in the book.

And a lot of it comes from Deepak. I agree with you — I would never think that story of betting $20 would have affected his schedule for this masterpiece, because when we think of Lynch, we’re told he just moves with the wind, he just wanders over here, and this thing happens. But when he was told you’ll never finish by midnight, it really lit a fire under him to get this done. And I think also Deepak’s story about getting the script for the first time for Lost Highway kind of demystifies this idea that Lynch doesn’t care what anyone thinks. He wanted feedback, he wanted someone to read his script, and he wanted it done in one hour and 46 minutes. We all feel that way. Sometimes I finish a chapter and damn, you want someone to read it (right away). So, I think there is a ton of who David maybe not is today, but who he was in 1997.

I was struck as well by the story of Gary D’Amico blowing up the cabin, and the fact that it wasn’t planned. Not that that is itself a skeleton key to understanding the film, but it is a moment that is pretty weighted in symbolism — the fire and rage within, both contracting and exploding outward — so it was fascinating to learn that it was a spontaneous decision.

Right, and I even go through the shooting script and there’s nothing about the cabin exploding at all. It just happened in that exact moment. It was kind of funny because some people would talk with me about it, and then some people wouldn’t, because they didn’t want to get David in trouble because they didn’t have a permit. But it was in the middle of the desert. I mean, who cares? They couldn’t be more remote, and also, it’s been 25 or 30 years, so I think the statute of limitations for blowing up a cabin that you had built has long expired.

I think David is fine. But it’s interesting how people want to protect him, and then also wanted to share about it as well. But I agree that in the end it says a lot about the character of Fred, especially if you think he was electrocuted at the end of the movie — that fire inside exploding you is very similar to what’s going on with his face during the police chase. I learned through my Fire Walk With Me book — there are things you think are so important, and (cinematographer) Ron Garcia would be like, “Oh, no, we just set the camera up right then and got that, he did that in editing.” It wasn’t there all the time. So, a lot of it has to do with (editor) Mary Sweeney knowing where to put that stuff. I think Mary Sweeney’s contribution to Fire Walk With Me and Lost Highway can never be diminished.

Do you think there’s a rehabilitation possible for Lost Highway today, given that the split-narrative aspect and associative logic perhaps aren’t as big of a deal to audiences today?

Well, we always like to end on a high note, so I’m proud to say no I do not. (laughs) I don’t think if it’s going to happen that it’s going to happen in this era that we’re living in. One, this movie isn’t going to stream (widely). Netflix is not going to kill themselves to get Lost Highway because they don’t want to get into that scene with Mr. Eddy and Alice. They don’t even want to approach something like that. And I don’t know that you can watch this movie and look at your phone and scroll Twitter at the same time. You’re just going to say, “This is crap, it doesn’t make sense.” We’re not there yet. So, I don’t think it’s going to happen. I don’t think it plays (theatrically very often), it’s not touring, although I’m trying right now to schedule a screening for this in L.A. in late June or July and try to get the cast, because you need to be in a theater where you put your phone down and put everything aside.

It’s not that complex of a film. And in fact, Balthazar Getty, he wasn’t trying to be funny, but he said, “Oh, this is Lynch’s most straightforward work he ever did.” I’m not going to go that far. (laughs) I think it is still complex, and you do have to pay attention. But we’re not ready to pay attention. We don’t want to think about art. And it just was re-released (theatrically) and it did worse than Inland Empire, which I point out in the book, which is another piece of proof that people aren’t ready for it. I think Inland Empire is getting more rehabilitation than Lost Highway. But I think Lost Highway is his tightest work. I’m never going to throw out the word best because that’s ridiculous. But it’s very tight. He isn’t always super-tight; he doesn’t mind meandering. And like I said, it ends in a fricking car chase — that’s ridiculous.

To order “Lost Highway: The Fist of Love,” click here: https://www.tuckerdspress.com/product-page/lost-highway. Additionally, there will be a very special screening of Lost Highway in Los Angeles at the Lumiere Cinema at Music Hall on the weekend of June 24. Check back for more details as they become available.