- Festivals

Becky Hutner Reimagines Fashion in her Tribeca Film

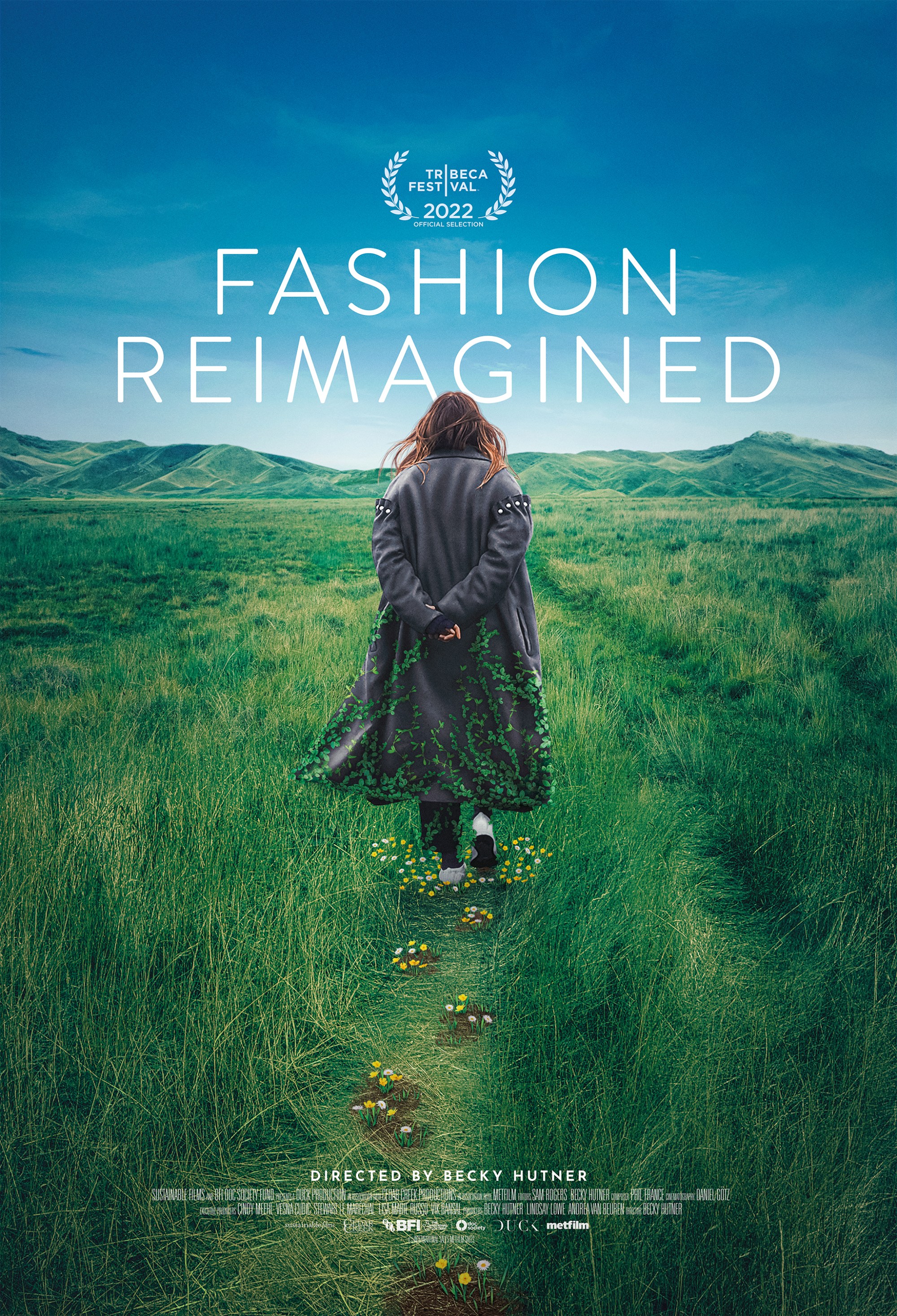

Fashion Reimagined, Becky Hutner’s documentary at the Tribeca Film Festival, follows sustainable fashion designer Amy Powney on her journey to create beautiful clothes while at the same time saving the environment.

Winner of the Vogue Designer Fashion Fund, Powney, who lived and grew up in a one-bedroom caravan she shared with her sister and her environmental activist parents, began the #FashionTheFuture campaign where she encourages people to rent, recycle, and repair clothes instead of buying dresses all the time. She also started the “No Frills” sustainable collection.

We interviewed Hutner, a filmmaker from Toronto who makes her feature directing debut with Fashion Reimagined. An Emmy-nominated film editor, Hutner worked on Seth Rogen’s Being Canadian and documented, in short form, fashion and culture for London Fashion Week and the National Gallery. Below are excerpts from our interview.

How did you meet Amy Powney? What makes her different from other fashion designers?

I met Amy in 2017 while working for a company called DUCK Productions in London which specializes in creating filmed content in the fashion space. I was assigned to make a short around the BFC/Vogue Designer Fashion Fund which is awarded to the top emerging designer in the UK. Amy won that year.

We did a shoot at her home. I asked what was next in her career. She began to tell me about her mission to create a sustainable collection from field to finished garment. She wanted to go all the way back to the beginning of the supply chain, meet the sheep, and the cotton farmers, and ensure that every step in the process met a specific set of environmental and social standards.

I happen to be on my own sustainable journey and in the past several years had made significant changes to my own lifestyle.

I knew that Amy was attempting something extremely challenging and important and that I was in a unique position to capture it.

What makes Amy different is the fact that she has focused on sustainability right from fashion school in the early 2000s when almost no one was talking about it. She entered this space from a working-class background with no connections. She didn’t actually start her label, Mother of Pearl. She got a job there as an intern and rose in the ranks to become Creative Director in less than 10 years.

Finally, she grew up off-grid in rural England with no running water. Her electricity came from a wind turbine her father built. Her humble beginnings could not be further from the London fashion scene.

How long did it take you to follow Amy? How was it traveling to different parts of the world and filming her?

We filmed for just over three years. Each location was a unique experience.

Uruguay was special because we met Pedro, the director of the wool business there. Out of one email from Amy’s colleague Chloe inquiring about his sheep, Pedro cleared his schedule for a week to show them his ranches and factories. We called him the Uruguayan David Attenborough.

In Peru, we all got altitude sickness from traveling to our destination at nearly 13,000 feet way too quickly.

Austria wins for best factory location. Seidra is a collection of wooden buildings nestled in the Alps right on the border with Italy and Slovenia. We were there in the fall and the forested slopes surrounding the factory were bursting with color and the sound of cowbells.

Due to budget reasons, we missed the original Turkey trip with Amy and Chloe. We had to make up the coverage during the pandemic, while I was pregnant.

What kind of challenges did you encounter while making this documentary?

Raising our budget as a first-time filmmaker, COVID, and juggling new motherhood with my multiple roles on this project were all extremely challenging.

Editing was challenging. I co-edited the film with Sam Rogers and it took us 17 months. We had to find ways to weave the hard facts about fashion’s impact that felt organic to Amy’s journey, which didn’t disrupt the story and that didn’t tip the scales into an “issue film.”

Also, how do you make an entertaining film about supply chains?

What is so unique about Mother of Pearl’s No Frills brand? Why do you think it took a long time for people to accept sustainable fashion?

Besides embodying a 360-degree approach to sustainability that considers the environmental, social, and animal welfare impact, No Frills was one of the first “sustainable” collections with a high fashion look. It’s one thing to do t-shirts in organic cotton. It’s quite another to do more complex garments like an evening gown or a suit.

It was very important to Amy that No Frills look no different from the regular Mother of Pearl collections. One of her markers for success was if customers couldn’t tell that the clothes were “sustainable.” She was fighting a stigma that used to go hand-in-hand with sustainable fashion – lots of neutral colors, sack-like silhouettes made of hemp.

You ended your documentary with a quote from Anne Klein who said, “Clothes won’t change the world, the women who wear them will.” Can you elaborate on why you chose this quote?

I have to credit our editor Sam Rogers with this choice which is playing so well with audiences. Both of us wanted to end the film with a message of empowerment and this quote, paired with the photo of little Amy pumping her fist in the air, reminds viewers of the little girl from the caravan who was bullied for being different, but rose above her circumstances and owned those differences.

Amy’s difference ends up being her superpower. I hope this ending makes people feel that they too can take inspiration from their own surroundings to make changes in their own lives that could have a wider impact.

This quote also recalls another quote, “Wear the clothes, don’t let them wear you.”

Amy’s #FashionTheFuture campaign is inspiring. What else do you think people in the fashion industry should do to save the environment?

Designers and brands should be practicing smart design with the entire lifecycle of the garment in mind.

Whether it’s choosing biodegradable materials, designing low-shed fabrics if they have to be synthetic to minimize microplastic, or offering repair, buyback, and resale services for your customers – these are ways to protect our natural resources and reduce waste.

We need to ramp up support for sustainable innovation in textile dyeing. It’s one of the most damaging processes in garment production, the second-most water-intensive industry in the world – using hundreds of toxic chemicals that pollute the waterways of marginalized communities in the global south, wiping out local fishing industries and causing infertility and rare cancers.

Scientists are turning away from chemistry and towards biology to develop more sustainable dye solutions.

Do you think the fashion industry has become more environmentally conscious?

Since I began following Amy in 2017, there has been an explosion of awareness in the industry – and in the wider public – about its environmental harms. Studies show that more customers are shopping based on their ethics. There is huge pressure on fashion brands to take these issues seriously.

What is extremely encouraging is the legislation that has emerged in the past few years. New York is deliberating the Fashion Act which would require any brand with a turnover of at least $100 million doing business with New York to map at least 50% of their supply chain, and disclose and mitigate their environmental and social impacts.

Brands would be required to disclose the total volume of materials produced. “Eco design” legislation has been introduced in the EU, focusing on durable, recyclable materials free of chemicals, and on the human rights side, the Garment Worker Act passed successfully in California in 2021, a historic victory that makes brands accountable for the workers in their supply chain.

What do you hope audiences will get after watching your film?

I hope audiences will have a better understanding of how clothes are made, of all of the people, animals, and resources that go into a garment across complex global supply chains, and the hugely detrimental impact of this process on people and the planet.

I hope this fosters a greater appreciation for clothes as items to purchase thoughtfully and cherish, not just buy on a whim and toss out later.

I hope our film can provide a clearer picture of what exactly sustainability in fashion really means. Almost every major fashion brand has jumped on the sustainability bandwagon, producing ancillary “sustainable” lines and doing the odd product out of recycled ocean plastic. But greenwashing is completely rampant, and these one-off projects are often a distraction from business as usual in which production and its harmful practices continue to accelerate.

By presenting Amy’s holistic view of sustainability across people, animals, and the planet, I hope we can help audiences to ask questions, probe deeper and not just take marketing at face value.