- Film

“Citizen Ashe”, the Black Tennis Champion and Social Activist

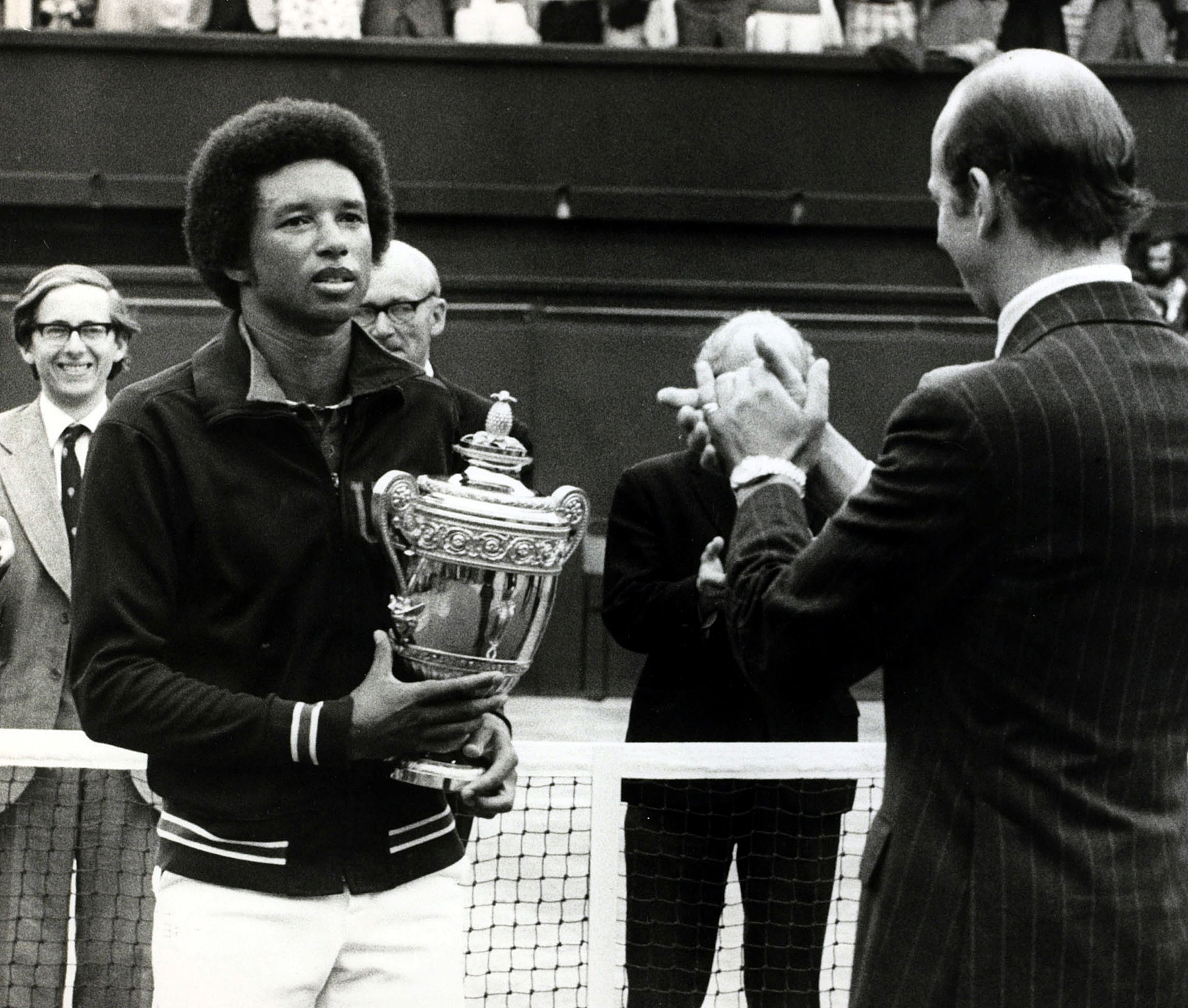

Many Americans, especially younger ones, may not know who Arthur Ashe was and how significant his achievements were in and out of the realm of sports. For starters, Ashe was the first Black tennis player selected to the US Davis Cup team and the only Black man ever to win the singles title at Wimbledon, the US Open, and the Australian Open. In addition to his groundbreaking sporting achievements and civil rights work in America, Ashe fought against South Africa’s apartheid system in the 1970s and 1980s, even getting arrested at a protest in Washington, D.C.

Citizen Ashe, Rex Miller and Sam Pollard’s new documentary, executive produced by Alex Gibney and John Legend, was made to correct that lack by showing the defining moments in the champion’s sports career and life. This CNN Films production world premiered at the 2021 Telluride Film Festival and will be distributed and streamed by HBO Max.

The film is a first-person exploration of Ashe in his own words, describing his own origin story as a social activist. Co-director Pollard explains: “I was a teenager in the 1960s and remember the extraordinary achievements of Arthur Ashe on the tennis court. But I knew little of the obstacles and challenges he faced on and off the court in the White world of professional tennis. Working on this film has been an absolute eye-opener into the man, and the player, who faced all of his challenges with a level of dignity and integrity we should all try to measure up to.”

Citizen Ashe blends archival newsreel, photos, and family footage, and reenactments, taking viewers along Ashe’s personal evolution that begins with a youth deeply influenced by his early tennis mentor, Robert Walter “Whirlwind” Johnson, and the death of his mother. Ashe was a trailblazer in tennis, a sport with a long history of White elitism. The documentary captures key moments in Ashe’s life, with race looming large throughout. For the African-American tennis champion, discrimination was an albatross that eventually motivated a thrust into the civil rights struggle. Issues related to racial justice, and the civic responsibilities of Black athletes, defined his life.

Confused by what being an African American athlete meant, Ashe, a Southerner who grew up in Richmond, Virginia in the 1950s, wanted to break the mold. Instead of taking up sports like track, baseball, and basketball, he chose tennis, because he wanted to be “the Jackie Robinson” of the sport, as his brother Johnnie Ashe, recalls in the film. The film compiles a compelling life story of a man who refused to be bullied, eschewing the use of his early celebrity as a tool in the civil rights struggle, only to eventually become a leader in the fight for racial justice and equality.

Citizen Ashe is a portrait that weaves together his on- and off-court life, with a running voiceover by Ashe himself from old taped recordings. Viewers are continually reminded that he was an amazing tennis player, one of the most brilliant tacticians to play the game. His takedown of a rambunctious Jimmy Connors at the 1975 Wimbledon Championship was widely hailed.

During his breakout years in the late 1960s, though he operated in the wealthy White circles of tennis, Ashe still faced racism on the courts. “It was not a picnic,” he said. At the same time, he was seen as a kind of “Uncle Tom” by some Black politicians. In order to survive, he repressed his anger and anxiety. He later admitted guilt in not speaking out or marching in protest as Black people “were getting their heads kicked in.”

With tennis becoming his obsession, he focused on winning, which he achieved at the young age of 25. However, as a new celeb, he had no experience with the media scrutiny that comes with that status. Suddenly, his off-the-court activities and opinions were of public interest. At the 1968 Summer Olympics, John Carlos and his Black Power salute on the podium with Tommie Smith caused much political controversy. More than 100 Black athletes boycotted the New York Athletic Club for its discriminatory policies.

Athletes were heroic role models, and Ashe’s initial reluctance to join the struggle didn’t necessarily sit well with other Black athletes. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar dismissed him as “Arthur Ass.” But the strong-willed Ashe wouldn’t be intimidated. “You grow up Black in the American South, you have no control,” Ashe says. “Your life is proscribed. And then in the 1960s, you have Black ideologues trying to tell me what to do. All the time, I’m saying to myself, ‘Hey, when do I get to decide what I want to do? I’ve always been fiercely protective with anyone trying to control my life.”

The year 1968 turned out to be his breakthrough in tennis. And before long, Ashe decided to become more active in the struggle. Inspired by “a social revolution among people my age, I finally stopped trying to be part of White society and started to establish a Black identity for myself,” he said.

That bold identity led to involvement in inner-city programs on behalf of social justice for African-Americans. In 1969, he campaigned for U.S. sanctions against South Africa and the nation’s expulsion from the International Lawn Tennis Federation. His South Africa activism would continue for years.

The feature contains footage of Ashe on the court, from his youth until retirement. He was often referred to as “Mr. Cool,” with an elegant technical form that helped him play at the highest levels in tennis. Interviews with Ashe’s widow, Jeanne Moutousammy-Ashe, his brother, Johnnie Ashe, as well as fellow tennis legends Billie Jean King, John McEnroe, Donald Dell, and Lenny Simpson, and activist Prof. Harry Edwards, illustrate the resonance of his historic Grand Slam wins, and how he managed a stoic dignity in public, despite the racism he endured.

Ashe would go on to win the singles title at the Australian Open in 1970 and Wimbledon in 1975, making him the only Black male player to win the trifecta, including the US Open. He is believed to have contracted HIV from a blood transfusion he received during heart bypass surgery in 1983. He publicly announced his illness in April 1992 and began working to educate others about HIV and AIDS.

He founded the Arthur Ashe Foundation for the Defeat of AIDS and the Arthur Ashe Institute for Urban Health before his death from AIDS-related pneumonia at the age of 49 on February 6, 1993. On June 20, 1993, Ashe was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by then U.S. President Bill Clinton.