- Film

Citizen Kane at 75

As film-lovers mark the anniversary of one of the most acclaimed movies of all time, the HFPA’s Phil Berk reflects on Orson Welles’ masterpiece

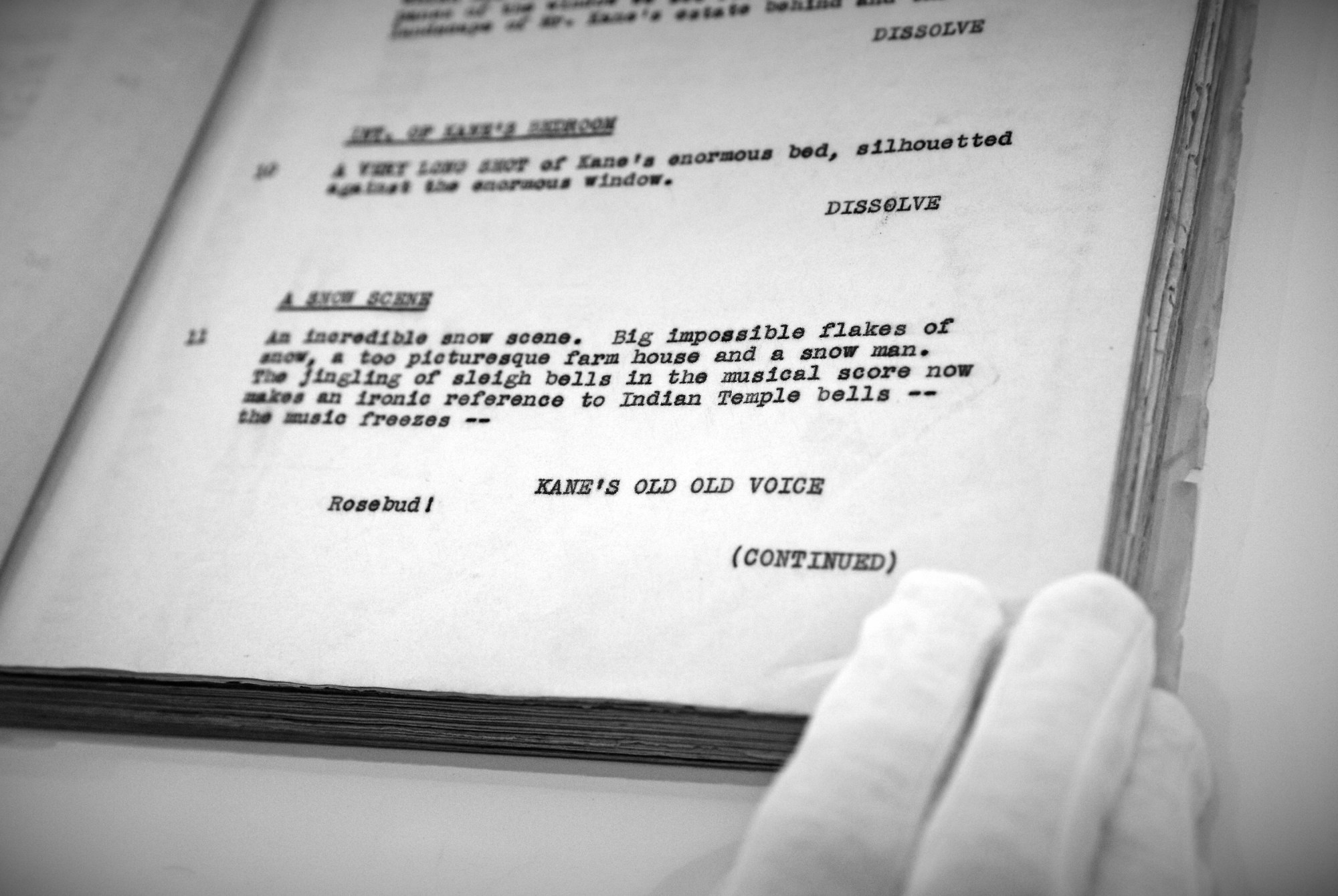

In the seventy-five years since Citizen Kane was first shown, no film in history has been discussed and debated more than Orson Welles’s masterpiece. For most film scholars, the only mystery of Citizen Kane is not Rosebud, but whether or not Welles actually wrote it. It always struck me as ironic that during his later years no one ever bothered to ask him this impertinent question. I was always able to dismiss this question by deferring to Pauline Kael (who was the first to validate the complaint.) When asked why Magnificent Ambersons wasn’t the equal of Citizen Kane, she replied ‘because Welles is not in it.’ In a similar fashion, I believe that without Orson Welles there would be no Citizen Kane. Every frame of the film is stamped with his genius.

If you examine the film, as I have done, over and over again, you will realize that every camera set-up in Citizen Kane was a labor of love. In every scene, Welles sets himself an inconceivable challenge. Even in the most complex scenes, he introduces impossible camera movements, symmetrical framing, actors moving within a shot yet always ending up perfectly framed. In no other film have master shots been used as effectively, not even by John Ford. The closest anything comes to being an “easy’ shot is the scene in which Kane first meets Susan Alexander. In the scene, she laughs, despite a toothache, when he is spattered with mud by a passing carriage. The spattering happens off-camera. Had it had been done on camera, it might have taken more time. But that is the only ‘easy’ shot in the entire movie.

At the other extreme is the famous scene at Mrs. Kane’s Boarding House. The scene opens with young Charles Foster playing in the snow. The camera pulls back to reveal both his parents and Mr. Thatcher discussing his future. All through the scene the boy, playing in the snow, can be seen through the window. Someone once said that the measure of a great film is whether more than one thing is happening on screen at any given time. In every shot, two, three, or more things are happening so the film becomes a voyage of discoveries.

Welles has always been credited with revolutionizing film techniques by his use of ceilings, overlapping conversation, deep-focus photography, low angle shots, etc., but Kael proved (in her famous essay ) that all of these had been used before, but never all in the same film. What Welles did revolutionize was the use of sound. Before Citizen Kane, no one experimented with sound the way he did. Coming from radio obviously, he knew the value of the medium. On a number of occasions, the film uses heightened volume to startle us, specifically in the News on the March opener, and when Mrs. Kane calls out, ‘Charles!’ in the Boarding House scene. Who can ignore the clanging of the door at the Thatcher Memorial Library, or the echo chamber effect there, and of course the screeching cockatoo in the final flashback?

To show the passage of time, another device borrowed from the radio is used, specifically in the classic montage sequence when we realize Kane and his wife are growing apart. Welles may not have revolutionized film technique, but his influence on Hollywood films of the forties is quite prodigious. One glaring example is Selznick’s Since You Went Away, the next year. Citizen Kane may have been reviled by the film colony (in fact the one Oscar it did receive, for the screenplay, shared with Mankiewicz, may well have been intended as a slap at Orson) but privately the filmmakers admired the film.

Beyond technique, there is of course content, and the greatness of Welles’s film is that, like Shakespeare, it was conceived not as a conscious work of art, but as a piece of popular entertainment. After all, this is the story of a man destroyed by his love for a woman! Some have called this aspect of the film trite and novelettish, but I disagree. For me, it embodies the Aristotelian definition of tragedy. Kane is the tragic hero, unable to alter the course of his destiny. As Jed Leland explains in the movie, Kane was a man who wanted people to love him. He believed if he did everything for them, they would reward him with love and gratitude, little realizing this type of behavior usually results in resentment and mistrust.

Which brings us to his performance in this film, arguably the best by an actor in an American film. His first appearance, following the newsreel footage, is absolutely wondrous. Welles plays Kane at 25 with brashness and an exuberance that is breathtaking. In the scene in which he makes a promise to Susan that she no longer will have to pursue her singing career, his acting is sublime, and in his final appearance, in the bedroom and down the corridor of mirrors, his acting assumes epic proportions. For that scene alone, Welles belongs to the ages!

Another remarkable aspect of the film is its use of narration, which is never employed as a crutch to explain necessary exposition or to tell the audience how to feel. When used, it’s for the sake of irony, juxtaposing conflicting points of view. Compare Susan Alexander’s recollection of the opening night of the Opera House to that of Jud Leland. Then there’s Bernard Herrmann’s score. Can anyone deny it’s the greatest score ever written for a film? Ironically, it’s not the greatest film score ever written. By itself, it loses its vibrancy, its sweep, its passion, but couple it with picture and dialogue, and it becomes unforgettable.

Lovers of the film consider the explanation of Rosebud a major weakness, but if you look back at the scene where Kane meets Susan for the first time, he explains that he had been to the warehouse ‘in search of his lost youth.’ Kane’s attachment to his mother, their separation when he was only five, explains his overwhelming psychological need.

Finally, there’s the editing, which in itself is nothing short of miraculous. In the closing moments of the film, notice the transition from Thompson’s question about the meaning of Rosebud to the inventorying of Kane’s priceless treasures. A series of dissolves ultimately unravels the mystery of Rosebud. In this sequence, Herrmann’s score reaches a crescendo that never fails to send chills down one’s spine.

Welles’s Citizen Kane is not American flim-flam, done with mirrors. It is an authentic masterwork, fit to stand alongside Huckleberry Finn and Moby Dick as the three great masterpieces of American art. It’s no wonder it’s been voted by Sight and Sound the best film ever made for fifty of its 75 years, And almost every filmmaker we’ve ever interviewed agrees.