- Film

The Cotton Club

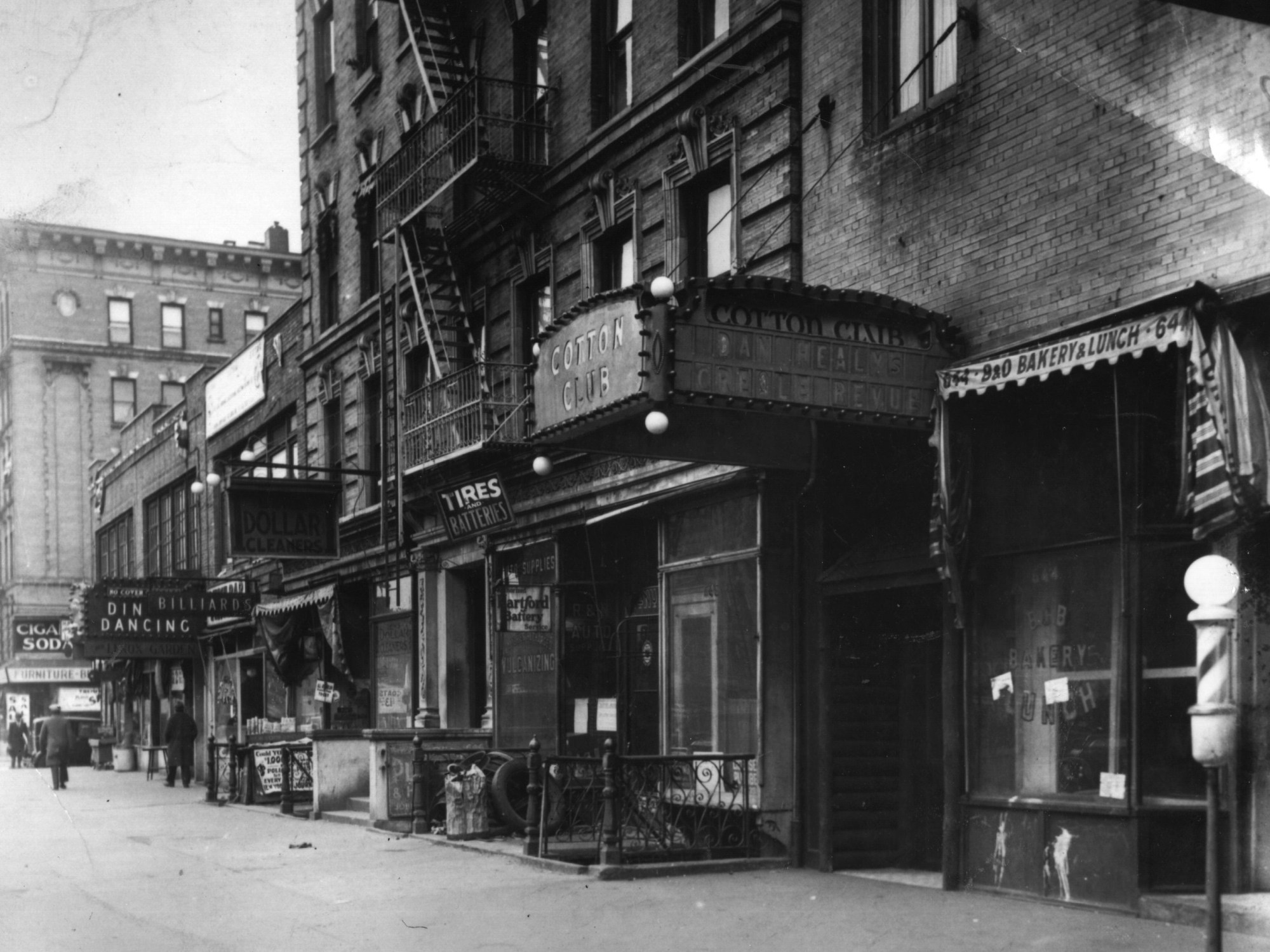

In 1923, a gangster and bootlegger called Owney “The Killer” Madden got out of Sing Sing jail and bought out heavyweight boxer Jack Johnson’s supper club, the Club De Luxe, on the corner of 142nd Street and Lenox Avenue, in Harlem. He renamed it the Cotton Club. It was a ‘whites only’ segregated speakeasy in the Prohibition and Jim Crow era where Blacks performed for a white audience.

A program book from 1932 calls the club “The Aristocrat of Harlem” and portrays a white man in a tuxedo and two white women in evening gowns and wraps being welcomed by a bowing Black maître d’.

“A stylish plantation environment” was the décor. The “jungle vibe” was reinforced by presenting the Black staff dressed as savages. Two tiers of tables were laid out in a semi-circle. Red tuxedoed waiters served: broiled filet mignon with French fried potatoes for $3, broiled lamb chops with julienne potatoes for $2.50, chicken chop suey for $2, and lobster American for $2.50 from an extensive menu. Champagnes like G.H. Mumms Cordon Rouge, Moet et Chandon Imperial Crown, and Louis Roederer were $12 for a quart and $6.50 a pint. A minimum of $2 per head was required to be spent on weekdays, $2.50 on Sundays, and $3 on Saturdays, “Holiday Eves” and holidays.

In his autobiography, “Of Minnie the Moocher and Me,” Cab Calloway said of the Cotton Club’s décor: “The stage set looked like a ‘Sleepy Time Down South’ stage set from the days of slavery. The bandstand was a replica of a southern mansion with large, white columns and a backdrop painted with weeping willows and slave quarters. The band played on the veranda. A few steps down was the dance floor, which was also used for floorshows.”

Dinner and dancing started at 9 pm. The entertainment started at midnight. There were floor shows and revues, some called Cotton Club Parades, with acts by singers, vaudeville performers, comics, tap dancers, and chorines – these girls had to be younger than 21, at least 5’6” and light skinned. They were advertised as ‘Tall, Tan and Terrific!”

The songs and scores for the revues were written by Dorothy Fields and Jimmy McHugh (“Diga Diga Doo,” “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love”), Harold Arlen and Ted Koehler (“Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea,” “Stormy Weather”), Irving Berlin and other famous white Broadway composers. The biggest hit of all the Cotton Club Parades was the one in 1934 featuring singer Adelaide Hall who sang “Ill Wind.” It ran over six months and had an audience of over 600,000.

Headliners included Ethel Waters, Louis Armstrong, Nat ‘King’ Cole, Sammy Davis Jr., Dorothy Dandridge and the Dandridge sisters, Lena Horne, Chick Webb, Fats Waller, Count Basie, Fletcher Henderson, Bessie Smith, the Nicholas Brothers, and Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, the latter earning $3,500 a week in his heyday, the highest-paid nightclub performer ever, Black or white. Josephine Baker was another performer who began her career at the Cotton Club, wearing a costume that comprised only a girdle of bananas.

On the riverwalkjazz.stanford.edu site, Margaret Moos Pick describes the floorshows: “A completely new floorshow was mounted at The Cotton Club every six months, and producer Dan Healy insisted the pacing of the floorshows be fast and furious. Dance routines were wild. Spotlights played over chorus girls dressed in a few strategically placed feathers and spangles. Elaborate stage sets and intricate lighting, combined with an ever-changing, star-studded cast, put Cotton Club revues on a par with anything on Broadway at the time. Glamorous blues singers Ethel Waters and Lena Horne and the exotic dancer Josephine Baker made The Cotton Club sizzle. Vaudeville great Bill “Bojangles” Robinson and the acrobatic tap-dancing Nicholas Brothers brought a taste of the Big Top to Cotton Club stage shows.”

From 1927 to 1931, Duke Ellington, in top hat and tails, and his orchestra were the house band. According to Moos Pick, Madden sent his “most persuasive goons” to Philadelphia where Ellington had a long-term contract with a club to get him out of it. “Duke Ellington and his men arrived at The Cotton Club opening night minutes before show time, on December 4, 1927.”

Ellington’s first revue featured Adelaide Hall and was called “Rhythmania.” She had previously recorded his famous “Creole Love Call.” He would develop an international career from his start at the Cotton Club, recording radio broadcasts on WHN, and later on CBS and NBC radio, some of which were made into albums. Cab Calloway and his orchestra took over as the house band upon Ellington’s departure in 1931.

From riverwalkjazz.edu: “Cab Calloway was all show biz on the bandstand. In this pre-rock and roll era, no one would dream of carrying on like Cab did. He waved his arms, strutted back and forth across the stage, and his hair fell in his face as he leaped into the air. Cotton Club customers fell in love with his zany antics, but Calloway was also a savvy bandleader; he drew some of the best jazz musicians of the day into his band. Bass legend Milt Hinton worked with Cab Calloway at The Cotton Club for years, and in 1939 while with Cab, Hinton wrote “Pluckin’ the Bass.””

“Celebrity Nights” were on Sundays and guests such as George Gershwin, Sophie Tucker, Jimmy Durante, Paul Robeson, Mae West, Irving Berlin, Fanny Brice, and Judy Garland turned up to see and be seen.

In 1935, Blacks were allowed into the club as customers. In 1936, after the race riots in Harlem, the Cotton Club closed its doors on Lenox Avenue. The neighborhood was not considered safe for whites. It reopened later that year on Broadway and 48th, in the Times Square theater district.

The club went out of business in 1940 for the same reason most supper clubs did – changing tastes, higher rents, the repeal of Prohibition, and tax evasion charges. In its place came the Latin Quarter nightclub, which lasted till 1989 when it was replaced by a hotel.

The poet Langston Hughes, prominent in the Harlem Renaissance, was not a fan of the Cotton Club, calling it “a Jim Crow club for gangsters and monied whites.” He wrote in his autobiography:

“Nor did ordinary Negroes like the growing influx of whites toward Harlem after sundown, flooding the little cabarets and bars where formerly only colored people laughed and sang, and where now the strangers were given the best ringside tables to sit and stare at the Negro customers–like amusing animals in a zoo.

The Negroes said: “We can’t go downtown and sit and stare at you in your clubs. You won’t even let us in your clubs.” But they didn’t say it out loud – for Negroes are practically never rude to white people. So thousands of whites came to Harlem night after night, thinking the Negroes loved to have them there, and firmly believing that all Harlemites left their houses at sundown to sing and dance in cabarets, because most of the whites saw nothing but the cabarets, not the houses.”

American director Francis Ford Coppola released the film The Cotton Club in 1984. It was based on a 1977 book of the same name by James Haskins. While the main characters were fictional, a lot of the supporting roles were based on real characters from the nightclub. Richard Gere plays a trumpet player at the Cotton Club who falls in love with the girlfriend (Diane Lane) of a Jewish gangster, Dutch Schultz (Bob Hoskins). The secondary plot involves tap dancing brothers played by Maurice and Gregory Hines. James Remar plays Madden. Nicolas Cage, Laurence Fishburne, and Gwen Verdon have supporting roles.

The film took five years to make and was nominated for Golden Globes for Best Director and Best Motion Picture Drama.