- Interviews

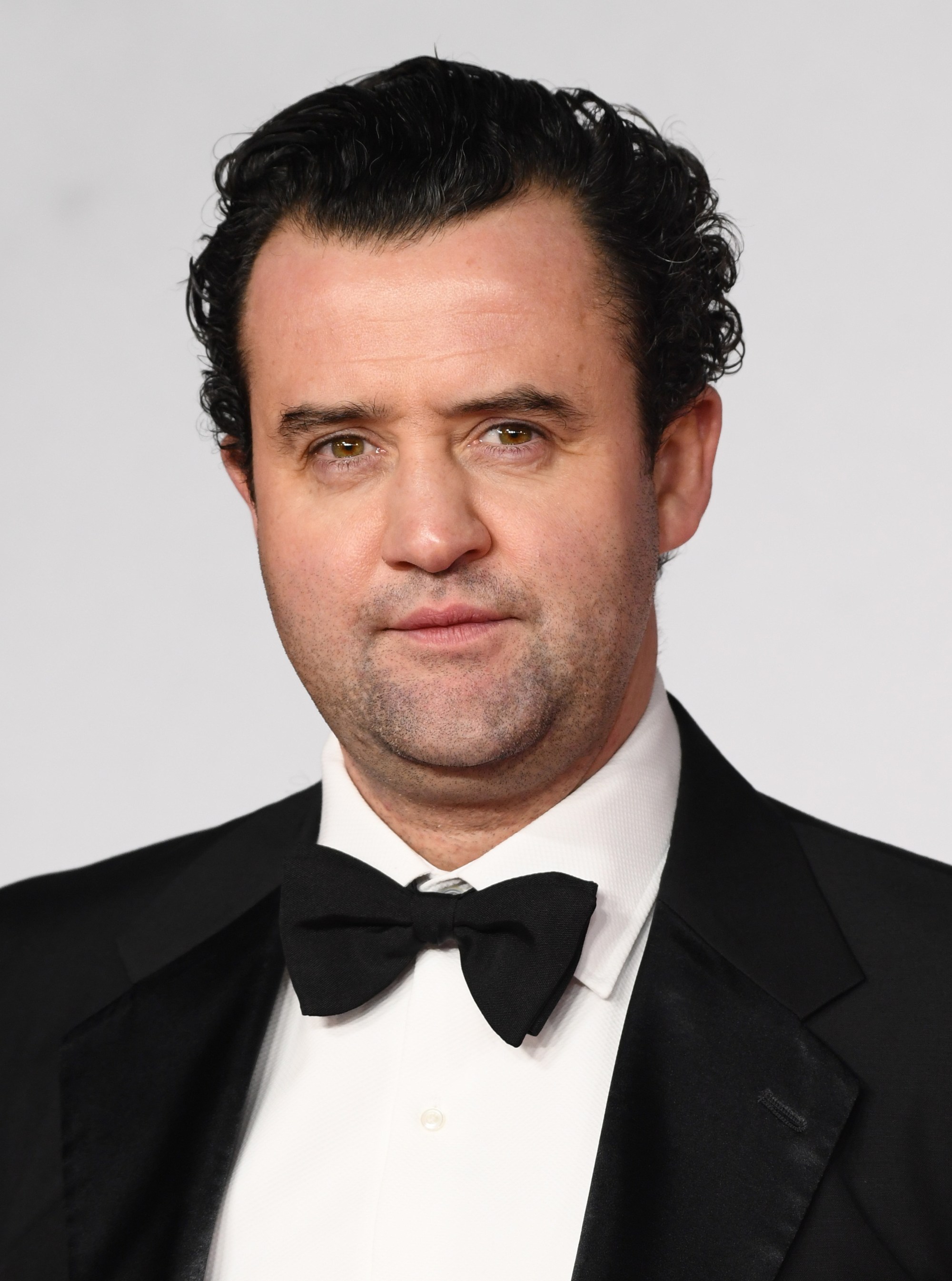

Daniel Mays: “I Just Want To Do My Job”

Daniel Mays is no stranger to cop shows. The English actor has portrayed policemen in a string of iconic TV projects – including Line of Duty, Life on Mars and Born to Kill – and he’s back to being a detective in the new British comedy Code 404, but there’s a technical twist to the tale. Speaking on a video call from the UK, the 42-year-old star of 1917, Vera Drake, and Atonement told the HFPA about his robotic new detective role, his work on the sun-filled series White Lines and his upcoming serial killer drama, How would you describe your upcoming Sundance Now show, Des?

Des is the story of a serial killer from the 1980s called Dennis Nilsen. Up until that point, Dennis Nilsen was Britain’s worst and most notorious serial killer. He went on a spate of killings of young vagrants and lonely young men over a five-year period. The story of the show is very much told from through the perspective of two men, one of whom was his biographer Brian Masters (played by Jason Watkins of The Crown). Brian befriended Nilsen and went on to write the brilliant book Killing For Company, which is what this drama is very much based upon. The other man is my character, who is the investigating officer and the detective responsible for convicting Dennis Nilsen, Peter Jay.

What can you tell us about Peter Jay?

Peter Jay is a very serious policeman who dealt with murder scenes and serious crime in the past, but nothing could’ve prepared him to deal with this level of evil. It’s very much a murder investigation in reverse because when they arrested him, Nilsen turned around and said, “I can now unburden myself.” When they first arrested him, he admitted to something like 15 murders. They literally interrogated him for two or three days and he didn’t stop talking. However, because he’d disposed of all of the bodies, it was a painstakingly laborious and financially taxing investigation for the police to get closure for the families. It’s a great depiction of what it was like to be a policeman in the early ‘80s when you’re dealing with a notorious killer like this and how that personally affects you.

Your Peacock comedy, Code 404, is vastly different. How was the show pitched to you?

I try to look at every script that comes along and I loved the writing of (Code 404 co-creator) Daniel Peak. My agent said to me, “Danny, you’re playing another policeman. You get killed off again.” And I was like, “We’ve been there, done that and got the T-shirt.” He said, “No, this policeman is brought back to life.” It sounded completely leftfield and bonkers. There was slapstick and it was one of those roles I could visualize myself playing straight away.

What makes the show stand out?

Code 404 has been described as a cross between Robocop and (iconic British ‘70s comedy) Some Mothers Do ‘Ave ‘Em. My character is a detective who is brought back to life, but the wiring is wrong. The idea of him being a brilliant policeman before he was killed and a really shit one afterward is a comedy of errors. I loved it because it offered me the opportunity to play in the comedy world again, which is a different kettle of fish. It’s a different discipline, but it’s one I really enjoy.

As an actor, what research goes into the portrayal of a rewired detective brought back from the dead?

There’s not much research you can do really. A lot of it was about instinct, but it was all there in Daniel Peak’s brilliant script. The inspiration for Code 404 comes from footage of a human-like robot that was put in a hot seat. They kept asking it quickfire questions and after about half an hour of attempting to answer these questions, the robot pretty much said, “I’m going to blow up the whole world.” That’s quite scary really. It makes you question the marriage between cyborgs, humans, and technology and how it can go disastrously wrong, which it frequently does.

Earlier this year, you had a lead role in Álex Pina’s Netflix drama, White Lines. What’s Álex Pina like to work with?

Álex doesn’t speak a word of English, so I was surrounded by translators the whole time. It’s funny… I kept getting thrown in swimming pools in White Lines. I was either drowned in them or I was thrown in them. When Álex Pina arrived on set, I said, “Please translate this: I don’t want to be thrown in any more swimming pools!” I’m a huge fan of Money Heist and when you get someone as talented and unique as Álex Pina, you know you’re on to a good thing. As soon as I saw the script for White Lines in lockdown is quite scary.

What conversations have you had about season two of White Lines?

I don’t think that’s going to materialize. It works brilliantly as a limited series because it neatly ties up the story of who killed the DJ Axel Collins, so I don’t think it’s going to happen. It definitely had legs in it and I would’ve loved to have played that character again because he was such a dream to play. I loved doing the show and I loved all of the ensemble actors involved. It’s up there as being one of the greatest and most enjoyable jobs I’ve been involved in, but I think that’s going to be your lot with it. That’s disappointing for sure, but it remains an extraordinary gift of a show and we’re very, very proud of it.

You’ve worked with cinematic icons including Steven Spielberg, Sam Mendes, and Mike Leigh. What’s the biggest lesson you’ve learned from them?

I was really lucky that I worked with Mike Leigh very early in my career. I was a year out of drama school when I was cast in All or Nothing and we got on like a house on fire. That led to being cast in Vera Drake, which was a commercial hit with Imelda Staunton leading it. Once you work with someone like Mike Leigh, the door is really opened in a commercial sense. Things started to snowball for me after that, but I was really grateful to learn from my time on his sets. It was an education. I did three years at drama school, but I think the experience of doing two Mike Leigh films back-to-back has pretty much shaped me as an actor. It gives you a bag of tools that you can use elsewhere. You try to apply that level of dedication, creativity, and instinct in everything you do from that point.

As an actor, what goes through your mind when you walk on to the set of a new project?

I guess the fear factor of walking on to big sets has dissipated over the years. I feel like I’ve got a significant body of work behind me now, although there are still butterflies when you first get called into Sam Mendes’ trailer on a project like 1917. It was obviously a very small supporting role – just like a lot of the guys in the movie, Andrew Scott, Mark Strong, Benedict Cumberbatch, and all those people – but Sam was amazing in that he felt each role was integral to the story. When you step on to a big-budget set like that, you have to be quietly confident that you can bring your A-game to it. I guess the more years you spend in the industry and the more jobs you get, the more confidence you have and you learn to have faith in your abilities.

What’s been your most memorable set?

I worked on The Adventures of Tintin in LA, which is a movie Steven Spielberg directed. That was incredible. I was nervous on that set because I was being directed by Steven Spielberg, and Peter Jackson was on a live video link-up. Plus, I’d never done motion capture before. It was bizarre because I was playing one of two henchmen, alongside Mackenzie Crook, but two weeks before we stepped on to that set, I didn’t know who was going to be playing the main baddie, Red Rackham. But then, all of a sudden, I’m standing next to Daniel Craig [as Rackham] and he’s throwing me up against a wall. We’re wearing funny wetsuits and it’s all a weird out-of-body experience. And because it was the early days of motion capture and the new technology was so impressive, lots of A-list actors were coming down to the set. I’d feel a nudging in my ribs from Mackenzie and I’d hear him say, “Look, it’s Tom Cruise.” And I’d turn around to see Tom Cruise was standing there with all these people around him. And then Clint Eastwood came down. The whole thing was a whirlwind, but I loved it. I thought the film was fantastic.

What’s the biggest difference between a British set and a Hollywood set?

It’s a different scale in the States. It’s a different size. I’ve done lots of low-budget, independent films in the UK – but it’s very different to the bigger US films. Mind you, the gift of directors like Sam Mendes on Joe Wright on Atonement is the fact that they make these huge budget films that have a sensibility of a low-budget British flick. They make you feel utterly integral to the story, so the huge canvas that you’re on doesn’t feel as big as it could. I think that’s the gift of good directors; if you’re able to communicate with them and not get lost in that huge wheel.

Sets are slowly starting to open up again. Are you ready to go back to work?

Hopefully, I’ll get back to work soon – but it’s a strange world right now. At the start of lockdown, I would say to people, “This is going to be amazing. There’s going to be this huge creative burst. There’s going to be all these writers sitting at home and they’re going to come out with lots of amazing film scripts. Offers are going to come in and I might even write myself.” But it just didn’t happen. I think the lockdown has put everyone out of their groove. It became all about staring at the four walls, home-schooling, and an hour’s exercise a day. It became laborious and very difficult, so I feel like I’ve got to get myself back into that working mindset.

What will sets look like when you return to work?

I don’t know how the mechanics of it are going to work, but I know there’s going to be rules and regulations. I don’t know how social distancing is going to work on a set, but I’ll find out soon enough. I’ve got a second season of Temple (with Mark Strong). To be honest, I just want to do my job. I don’t want to be worrying about all of that stuff. I’m intrigued to see what happens. I’m sure we’ll muddle on through.