Disabled Characters Still Largely Invisible in Hollywood

Disability representation in the movies has more lows than highs. According to the CDC, one in four U.S. adults have a disability, but that’s far from reflected in movies.A recent Annenberg study looking at 1,800 of the most popular films last year showed the number of disabled characters on-screen is still 2.4%, the same number it’s been since 2015. And the majority of disabled characters remain predominantly white men played by abled actors. “I still see stories where disability is kind of a subplot, maybe tokenized, but not really shaking any trees industry-wide,” said Lawrence Carter-Long, director of engagement for the Reelabilities Film Festival.

In comparison to last year, when movies like Aaron Schimberg’s A Different Man (for which Sebastian Stan won a Golden Globe) and the William Goldenberg-directed Unstoppable were putting disability front and center, this year’s movies seem more disabled-adjacent. There are disabled characters in the likes of Thunderbolts (Sebastian Stan’s Bucky Barnes is missing an arm), as well as the live-action How to Train Your Dragon. And while both movies integrate disability into the character’s everyday lives without belaboring the point, the use of CGI means there isn’t much need to cast authentically.

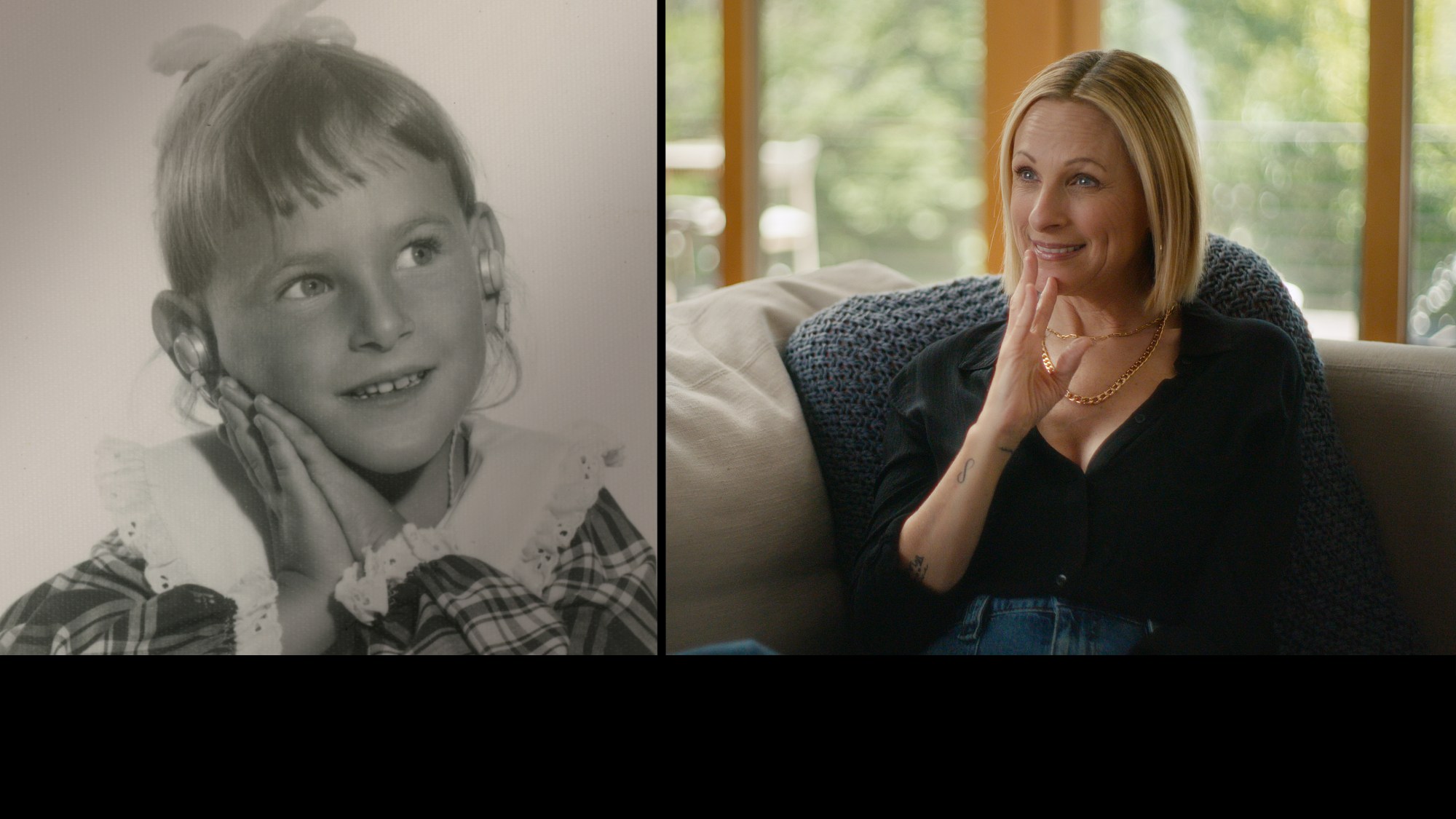

TV has given us works like Patrice: The Movie and Love on the Spectrum. There are also fantastic documentaries out there like Shoshannah Stern’s Marlee Matlin: Not Alone Anymore, Reid Davenport’s Life After and Nyle DiMarco-Davis Guggenheim’s Deaf President Now! Other features, like this year’s Song Sung Blue, fall back on outdated stereotypes of disabled pain and tragedy.

But there are continued signs of wanting to be more inclusive. As Carter-Long says, Hollywood is more open to championing the anomalies, the movies that aren’t exactly big-budget features but have done well on the festival circuit. One example is Mary Bronstein’s If I Had Legs I’d Kick You, the story of a put-upon mother (Rose Byrne) struggling to care for her temporarily disabled child.

The story is about a caregiver trying to find her own identity while caring for her child, and how she tries to balance autonomy, guilt and resentment for her situation. As Bronstein told me in a recent interview, “If somebody with a disability, or with complicated health needs, or with a chronic illness feels seen, or if a caretaker of such a person feels seen by this movie, I’m all for it.” However, Bronstein also feels she can’t tell a disabled narrative because she isn’t disabled, advocating that those with disabilities should be telling their own story. It’s clear there’s enhanced awareness that disability needs to be told by those with lived experience.

The upcoming release of Wicked: For Good is one such place where the disabled community is hoping to see progress, particularly as the original Broadway show has seen its own share of critiques for how it portrays the wheelchair-using character of Nessarose. Carter-Long is cautiously optimistic that, much like the first film, the sequel will give Nessarose something unique. “Her longevity, in terms of a career … I would like to see that extended beyond one actor and in a series of films or a franchise. That’s the next important step that we need to be making.”