- Film

Docs: “Attica” – “A great history lesson. Not to be repeated.”

It’s regarded as one of the most violent forms of repression which America uses against its own citizens, certainly the most violent in the U.S. prison system. The rebellion – or riot – which took place in September 1971 for five days in the state prison of Attica, New York, for better living conditions, concluded when then Governor of the State of New York Nelson Rockefeller – with the full approval of then-president Richard Nixon – ordered bloody repression.

The Attica “rebellion” ended in a bloody massacre, with 43 people killed: 33 inmates, 10 among guards and prison workers. That tragic event is now the subject of the documentary Attica by directors Stanley Nelson and Traci Curry. It’s Oscar-nominated for Best Documentary and is now available on Showtime; it is now free until the end of April on YouTube in honor of Black History Month.

The event sent shock waves throughout American society at that time, revealing the brutal treatment of prisoners in US prisons, especially against wards Black and minorities prisoners. In the classic 1975 Sidney Lumet film Dog Day Afternoon, the hapless gay robber played by Al Pacino is encouraged by the crowd outside the bank with the enthusiastic chant “Attica! Attica! Attica!”, in protest against the “white”.

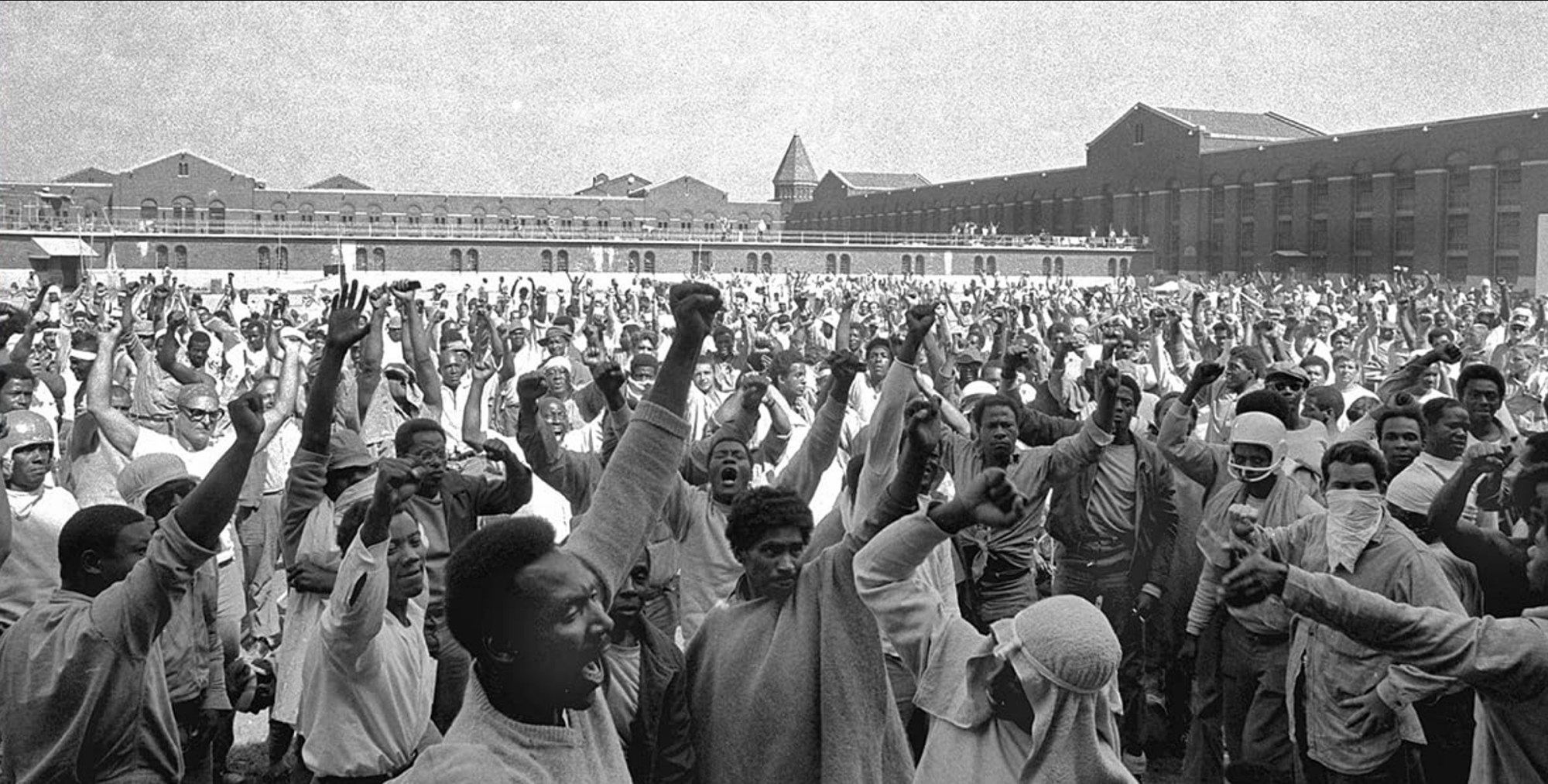

Attica, the documentary, starts on the very first day of the rebellion and chronicles day after day the taking over of the prison’s main courtyard by over 1,200 prisoners, mainly Black. They took 12 hostages and demanded to meet with the prison director to negotiate.

The film recounts the brief visit paid by Black Panther’s leader Bobby Seal, the falling out of the negotiations, and the decision to send hundreds of heavily armed soldiers, including the National Guard, into the prison to put a violent end to the rebellion. The aftermath is even crueler: every single surviving prisoner was forced to strip naked and crawl through feces and latrines in the open air and run through a gauntlet of beating guards on broken glass.

The documentary doesn’t spare details in its last half hour of the description of the horrors inflicted on the prisoners through photographs which were brought to a court case. Without narration, the events unfold through interviews with surviving prisoners, negotiators, and journalists who were covering the events. Stanley Nelson preferred to call it a rebellion, over sub-human treatment.

Nelson (The Murder of Emmett Till, Freedom Riders) was around 20 at the time. For at least the past two decades, he had been thinking about making a film about Attica. “When Traci Curry and I first started thinking about the film, we asked our staff, which was like 25 people at that time, who knew about Attica,” Nelson told Yahoo! Entertainment. “And easily, a third of the people on the call said they didn’t even know what Attica was. We realized people were going to be really shocked by this story if we told it.

Ninety-nine point-nine percent of people, even if they knew the broad outlines, didn’t really know the details of what happened. The film goes down to the root of that problem, which was the state’s abuse of power, and the way in which law enforcement was this blunt instrument to reassert the authority of the state.”

“It was never far from our minds that we are asking people to revisit a profound trauma,” Curry told Yahoo!. “And sitting with people in that, just as a human being, you can’t help but be affected by it.”

Attica was made in the middle of 2020, with the COVID pandemic and the Black Lives Matter protests that followed George Floyd’s murder at the hands of the police, and, according to its directors, “it should and will be an eye opener”, especially for young audiences, over the injustices of society. Attica is therefore a great history lesson. Not to be repeated.”