- Film

Docs: “Attica!”: Seminal Documentary Revisits the Tragic Prison Rebellion of 1971

Attica! is a riveting documentary that revisits an American tragedy exactly 50 years after the prisoners’ rebellion at the Attica correctional facility in upstate New York which would become infamous in American prison history. On this anniversary the revolt has spawned several retrospectives, such as HBO Max’s Betrayal at Attica.

The latest work by filmmaker Stanley Nelson (who has helmed Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool, Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution, and Freedom Summer) “celebrates” its 50th anniversary in a deeply researched documentary. Rather than taking a dry historical approach, Attica! offers an emotional journey to the past, with riveting footage and privileged interviews with those from all sides of the largest prison riot in US history.

It is not the first feature about this painful subject. In 1974, Cindi Firestone’s documentary, Attica, provided a rare, firsthand view of life inside a prison yard where a thousand inmates rebelled against harsh and brutal prison conditions, which led to the takeover of New York’s Attica State Prison in 1971.

Some viewers probably know of Attica only from its being referenced in Sidney Lumet’s 1974 Dog Day Afternoon, when Al Pacino’s chant of “Attica! Attica! Attica!” while robbing a Brooklyn Bank.

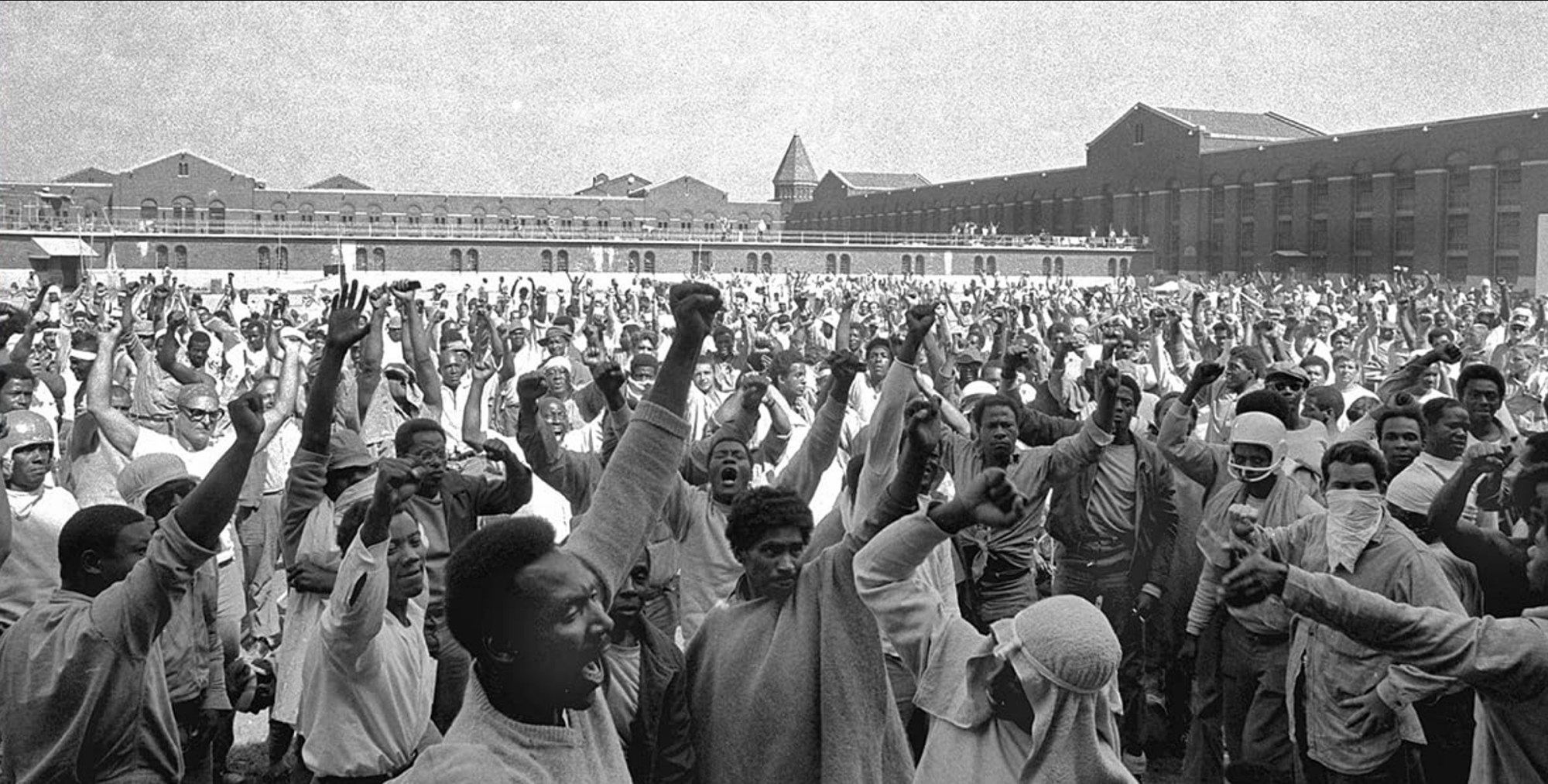

Some context is in order: The events took place at Attica between Sept. 9 and Sept. 13, 1971, culminating in armed figures taking control of the prison and killing dozens of prisoners and hostages alike. On Sept 9, more than 1,200 Attica inmates took control of the D-Yard in the heavily fortified prison 235 miles north of New York City and held hostage 42 officers and prison employees. Located in a small upstate village of mostly White residents, the prison hired mostly White) locals to keep the predominantly people of color prison population in check.

Over four days, they engaged with New York State Department of Corrections leaders, summoning an assortment of public figures to serve as mediators and sympathetic figures in what became a public affairs scandal in addition to an unraveling standoff.

Though in the beginning there was no leader, no order, and everyone seemed to be on their own, all inmates, Black, White, and Puerto Rican, quickly began to work together for the first time. Many had been in Vietnam and knew how to make tents for shelter, or dig latrines to survive. They set up a medical service in the yard that was better than what they were used to as prisoners.

The protest was wide-ranged, against cruel conditions in prison where White prisoners received special attention, where Black Muslims were denied religious rights. Many were affected by the untimely death of revolutionary activist George Jackson in San Quentin prison. It began by refusing meals, which startled the guards and showed them the prisoners looked organized.

Nelson should be commended for seeking out subjects who haven’t always been given a platform to tell their sides of the story. Inmate LD Barkley, one of the victims, had only been sentenced to 90 days in Attica. He played a leading role and read out the demands that were collectively developed that included better prison conditions and religious freedom.

A Jewish lawyer prisoner, Jerry Rosenberg, highly respected by most inmates, helped them through the legal process. He said that the injunction was not legal without a signature, and turned the team against the negotiations.

Commissioner Oswald began as lead negotiator and eventually left, as Governor Nelson Rockefeller, in constant contact with President Nixon, made it clear there would be no acceptance of the prisoners’ demands. What made things worse is that Rockefeller refused to appear in person at Attica.

Certain public figures were asked by the inmates to come to Attica to help in negotiations. Black Panther Bobby Seale came for only three minutes and remained aloof, which disappointed the inmates. They invited Tom Wicker, a New York Times editor who wrote of his role in a Pulitzer Prize-winning book, A Time to Die.

William Kunstler became the main legal voice for the inmates. Claude Jones of the Amsterdam News was a negotiator, who now gives an emotional interview in the feature. When it was learned that one of the guards, who had been injured during the initial prisoner rush, died in the hospital, the negotiations became almost futile. Prisoners were forced to drop all demands except for amnesty. During the long weekend of negotiations, tensions elevated outside the prison walls among the families of the White guards, while the police and military seemed to be impatient to go in and get the Black rioters.

The weekend tragedy came to a climax when prisoners were forced to move out of the mud-soaked lot onto the concrete sidewalks outlining the grounds. Sensing impending doom, prisoners placed knives on the necks of the guard hostages trying to ward off a possible attack. A racial battle of revenge led to the uncontrolled torture of survivors.

It may be ironic to note that it was the Black Muslim inmates who saved the lives of some of the guards throughout the ordeal because they believed in treating captives fairly.

In 2000, after a 25-year battle, former Attica prisoners received a $12 million settlement from the state. In 2005, the surviving hostages and families of the hostages killed also received a $12 million settlement from the state.

Nominally, the perceived battle was between law and order and anarchy and chaos, but, ultimately, the evil of mass incarceration was exposed and prison reform was put on the agenda. However, it is sad to report that prison reform is still high on the national agenda today.