- Industry

Docs: “Bad Vegan” Satiates Audiences Hungry for Offbeat True Crime Tales

Not long ago, documentary films used to struggle to find market share. Only a small handful of brand-name auteurs, like Michael Moore and Errol Morris, would receive consistent wide-scale international release, and big box office breakthroughs, like the $127 million worldwide haul of 2005’s March of the Penguins, were few and far between.

Things have changed, however. While the advent and rapid growth of streaming platforms may have clouded the picture of the theatrical exhibition for much of Hollywood’s product, one undeniable beneficiary of their embrace by consumers has been the community of nonfiction storytellers — particularly those operating in the true-crime sphere. From white-collar swindles to murder and everything in between, audiences have fallen hard for tales of people behaving badly, and digital content providers have been only too happy to surf the wave of this trend.

Enter into this space the curious and fascinating Bad Vegan: Fame. Fraud. Fugitives., the latest effort from filmmaker Chris Smith, who produced the early-pandemic zeitgeist smash hit Tiger King, and also recently directed both Fyre: The Greatest Party That Never Happened and the eight-part The Disappearance of Madeleine McCann.

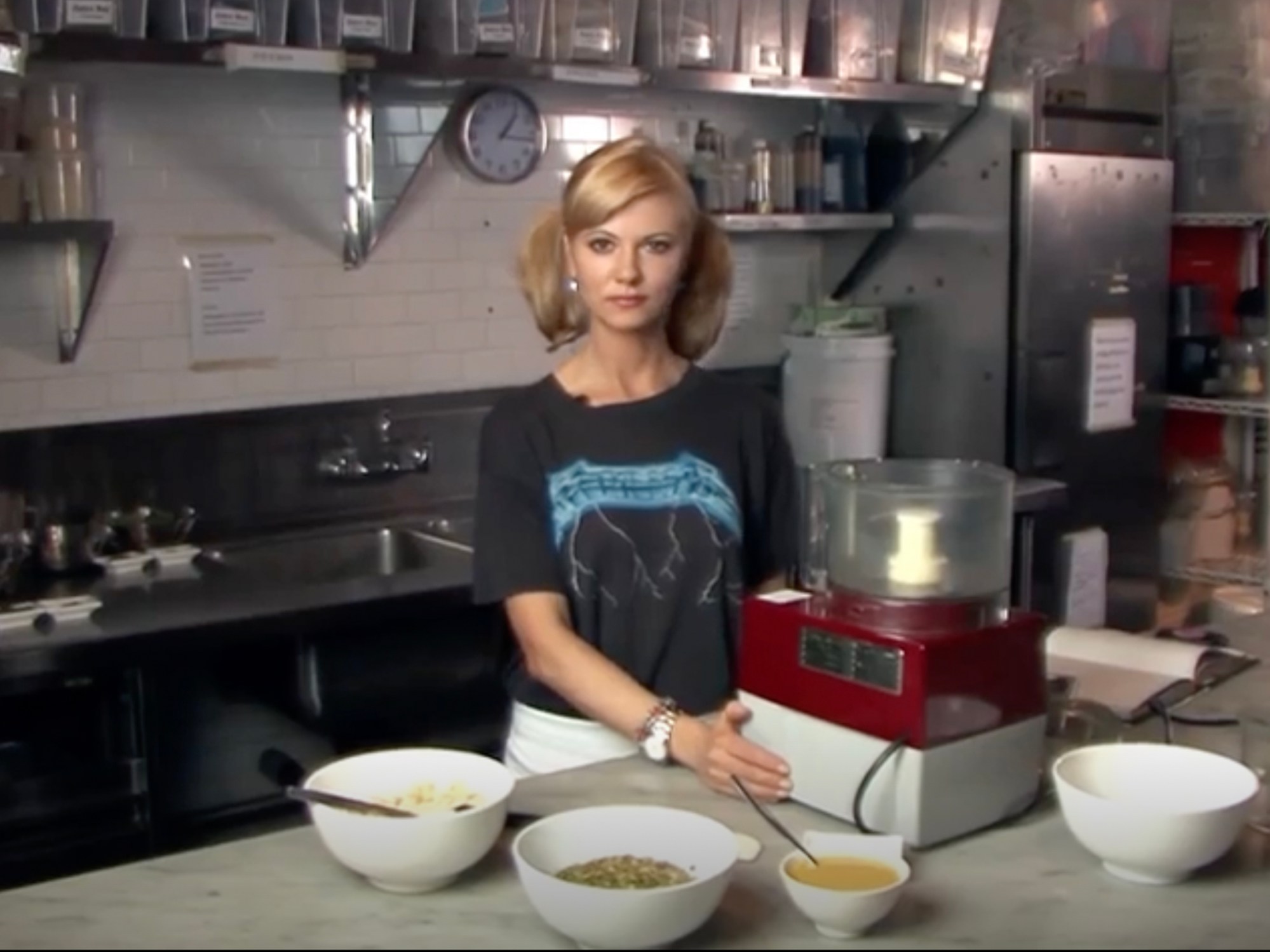

The title character of his new four-hour Netflix docu-series is Sarma Melngailis, owner/proprietor of the high-end New York City raw vegan restaurant Pure Food & Wine, which in the early 2010s counted among its trendy clientele Woody Harrelson, Owen Wilson, and even Bill Clinton. As her eatery flourished in profile, it would still struggle to turn a reliable profit, and it was against this backdrop that Melngailis would meet online a man named Shane Fox (real name: Anthony Strangis) and enter into a relationship with him.

Over a period of several years, Strangis would come to use both Melngailis’s restaurant and its offshoot brand, One Lucky Duck, as a personal bank account. After twice failing to make payroll, Melngailis and Strangis would disappear together, forcing the restaurant to close. Many months later, their shared life on the lam would end in a budget hotel in tiny Sevierville, Tennessee, not far from tourist attraction Dollywood, a theme park owned by singer Dolly Parton.

The final numbers are staggering: $1.7 million siphoned out of Pure Food’s business accounts for Strangis by Melngailis; another $400,000 or so from her mother; and a total of $6.1 million in total debt racked up by the pair when factoring in defrauded investors. Was it, as Melngailis would later convincingly claim, a case of psychological coercion and twisted mind control? Or something else?

There’s a surface-level fascination to this type of story, but it’s the handful of gaudy, eyebrow-raising details which really put the hooks into a viewer. First, there’s how Strangis framed his repeated asks for wire-transferred money as tests (which would seem to have served as partial inspiration for Resurrection, which premiered at this year’s Sundance Film Festival). Then there’s the fact that Strangis, who described himself professionally as a shadowy mercenary, also portrayed himself quite literally as an angel doing battle with demons, promising to make Melngailis’s beloved dog (and possibly even her) immortal. Finally, there’s the fact that the duo was eventually located by way of a credit card payment on a delivery order of pizza and chicken wings from Domino’s Pizza.

Smith, who crafted one of the most stirring, melancholic, and exquisite snapshots of the wayward creative impulse of the last quarter-century with 1999’s award-winning American Movie, is a talented filmmaker. He has a gift for locating humanity in flawed characters. And he can be a good interviewer too, as proven by his Emmy Award nomination for Jim & Andy: The Great Beyond.

So, it’s a bit disappointing that Bad Vegan doesn’t quite seem to crack the poised emotional aloofness of its subject, whose psychologically protective shell comes off as a bit candy-coated. The series feels deferential to Melngailis’ supposed fragility and too polite by half. This latter element is most robustly demonstrated when, for example, Melngailis admits to using an alias and covering up her tattoo but denies ever feeling like she was a fugitive on the run.

The appearance of Alec Baldwin as a kind of (non-interviewed) cameo player in Bad Vegan’s first episode might initially seem surprising or come across as an unnecessary embellishment — just a way to add one more layer of celebrity to this already weird tale. But, by the project’s conclusion, it actually makes perfect sense.

Melngailis comes across as wholly, sincerely dedicated to the promulgation of vegan cooking, but also pushed, perhaps by her own depression or other mental health issues, into an unmotivated place where she was simply casting about for an anchor — someone rich, famous, or some combination of the two — to relieve her of the burden of actually doing anything for her business other than posting pretty, lifestyle-confirming photos on Instagram. After Baldwin, having had his flirtatious advances rebuffed by Melngailis (who was concerned about their age difference), eventually met his new wife Hilaria Hayward-Thomas at Pure Food & Wine, it’s not at all a stretch to see Melngailis’s embrace of Strangis as less a case of someone ignoring copious red flags, and more a magnetic attraction specifically toward fancifully vague promises of financial security and, eventually, deified ascension.

Yes, Melngailis is a victim of Strangis, who slowly bent her to his diseased will. She is also arguably a user in her own way (as her subsequent affair with her married lawyer Jeffrey Lichtman, not mentioned here, would confirm). Perhaps unintentionally, Bad Vegan shows someone who exploits in a low-key, almost vampiric way the oft-mentioned nature of her conventional attractiveness in order to get other people to do the work of bettering her fuzzy dream and enabling her comfortable lifestyle.

In this way, Melngailis isn’t just yet another colorful true-crime character, like Tiger King’s Joe Exotic. Her commingled transgressions and victimhood mark her as a kind of uniquely symbolic, fail-upwards avatar of the still-young social media era — someone consumed by the visual trappings of success of others, content to coast along and trade on privilege without asking questions of others, or themself. One can detest Strangis (broken and manipulative in more conventional ways), have some baseline sympathy for Melngailis, and still feel uncomfortable with and unnerved by her being centered (and in some ways almost celebrated) as a character. Bad Vegan provides a look into the cracked mirror of society. Whether most of its viewers – or even Smith himself – fully recognize that, is an open question.