- Film

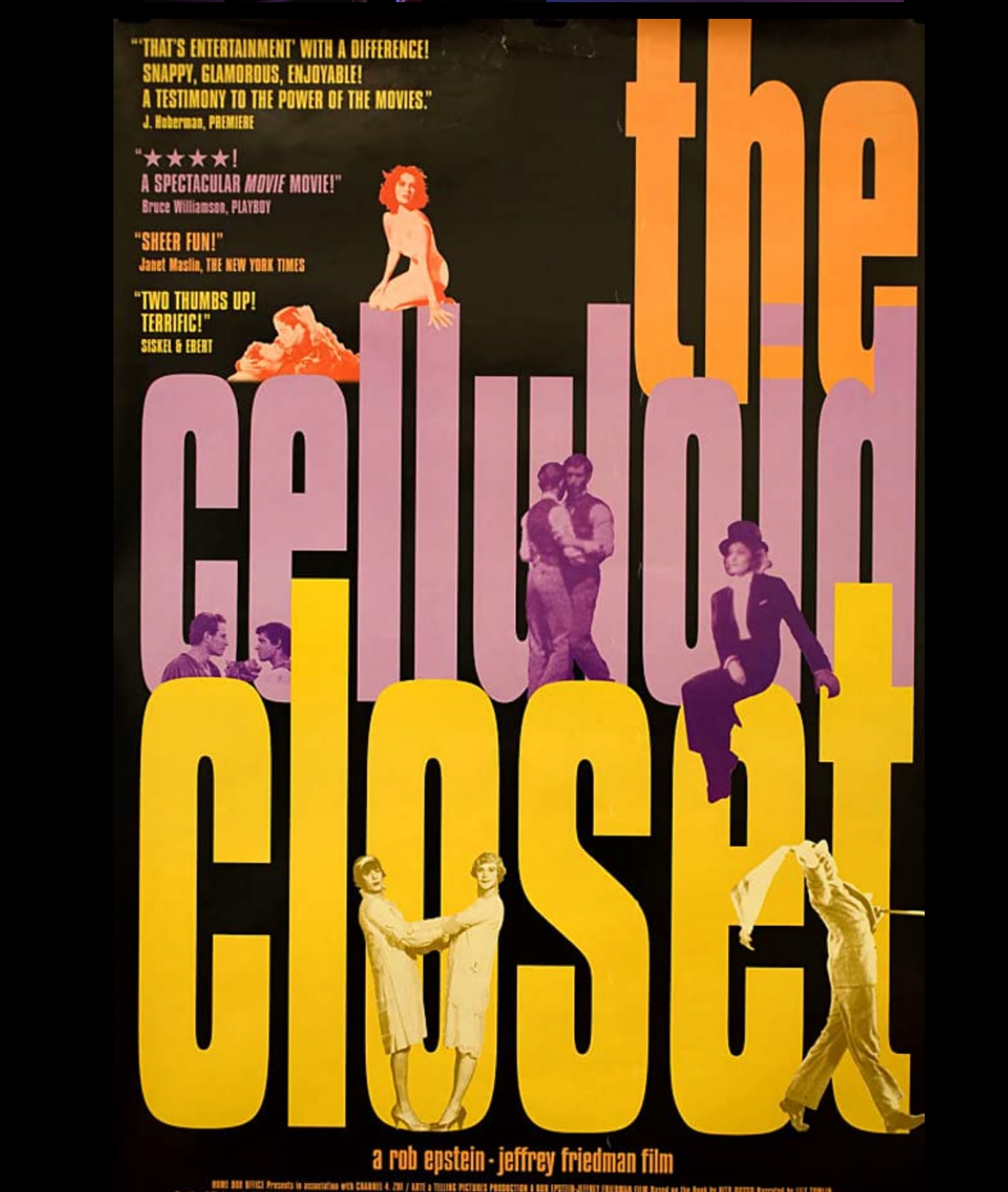

Docs: “The Celluloid Closet” – Queer Representation in Hollywood Cinema

In the 1981 book, “The Celluloid Closet: Homosexuality in the Movies,” film historian Vito Russo traces the history of queer representation in the movies. The book was adapted into a documentary of the same name in 1995 by Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman and was shown extensively on HBO.

In 1894, a British inventor by the name of William Dickson, who was an employee of Thomas Edison, made a film with live sound that is said to be the first known film. In the 17 seconds that were found and restored, the film shows two men dancing while Dickson plays the violin in the background. This film has been hailed as the first gay film by Russo in his book and in the documentary, though there is no evidence to suggest that the men were gay or that it was Dickson’s intention to portray them that way. However, it is the first known example of two men in an intimate embrace and thus was worth citing.

The 1922 silent film Manslaughter, directed by Cecil B. deMille, is said to have the first gay kiss between women – Lydia, a society girl played by Leatrice Joy kisses another woman in a party scene.

Wings, director William A. Wellman’s 1927 silent film, features the first gay kiss between men – on a deathbed. Up until the final kiss, the two men were portrayed very carefully as close friends, and the film won the first Oscar for Best Picture.

Most portrayals of homosexuals in movies, which have sporadically existed since the birth of cinema, were always shown through a straight lens, making them palatable to audiences by turning them into jokes or villains.

In the teens and 20s, cross-dressing jokes were common as in Charlie Chaplin’s 1916 Behind the Screen, when a stagehand mocks Chaplin with swishy gestures as he is kissing a boy – unbeknownst to him, Chaplin is actually kissing a girl dressed as a boy.

But in the early 1920s, after the Fatty Arbuckle trial where he was tried (and eventually acquitted) of rape and manslaughter, and the scandal created by the murder of gay director William Desmond Taylor, Hollywood was perceived as a den of iniquity and politicians seized on the furor created by religious groups like the Catholic Legion of Decency to introduce tens of censorship bills in their states.

Afraid of government intervention, in 1922 the movie studios collaborated to hire Will H. Hays to police Hollywood’s morals. They inserted ‘morals’ clauses in their stars’ contracts. Lavender marriages were hastily set up for their gay stars and the studio’s ‘fixers’ hushed up or paid off cops and politicians to cover up any whiff of scandal. In 1927, Hays established the ‘Production Code’ or ‘Hays Code’ for self-censorship in Hollywood, which prohibited, besides other subjects that might offend the tender sensibilities of audiences, ‘any inference of sex perversion.’ That, of course, included portrayals of homosexuality which was considered perverse and deviant behavior.

In the beginning, the Code was voluntary.

Creative minds got around the problem of directly referring to homosexuals by creating stock effeminate characters like the ‘sissy’ who appears in several movies, including Westerns like 1927’s A Wanderer of the West and 1923’s The Soilers. A flamboyantly nervous designer is portrayed by Jed Prouty in 1929’s Broadway Melody and Edward Everett Horton was a swishy bewildered reporter in 1931’s The Front Page.

In The Celluloid Closet documentary, writer Quentin Crisp explains, “Sissy characters in movies were always a joke. There’s no sin like being a woman. When a man dresses as a woman, the audience laughs. When a woman dressed as a man, nobody laughed. They just thought she looked wonderful.”

The challenge to the patriarchal notion that happy lesbians were threats to marriage and procreation was considered serious enough that lesbians were not caricatured as funny onscreen. They were grim, tormented, self-hating, villainous, sometimes all at once, and usually came to a bad end through murder or suicide.

Villainous screen lesbians included Gloria Holden as Countess Marya Zaleska in 1936’s Dracula’s Daughter who hunts down and seduces women; Judith Anderson as Mrs. Danvers in the 1940 film Rebecca, who is obsessed with her late mistress; and Mercedes McCambridge as a lesbian biker gang leader who watches bikers terrorize a woman in 1958’s Touch of Evil.

In Caged, there is a monster of a prison matron who is gay and ends up dead; in The Fox, Sandy Dennis is seen as a pathetic spinster mourning the loss of her lover; in Joseph Mankiewicz’s Suddenly Last Summer, based on Tennessee Williams eponymous play, the gay man is killed, his face never shown, and his homosexuality is hushed up by his mother in a monstrous way; in Johnny Guitar, psychosexual overtones are present between two women throughout the movie till ‘order’ is restored when one woman kills the other.

Here are examples of gay male villains – In Alfred Hitchcock’s 1948 Rope, two men murder their friend because they think they can get away with it. It is clear that the two are lovers, as Hitchcock based them on the notorious Leopold and Loeb murders, two gay men who wanted to commit the ‘perfect crime.’ Peter Lorre in The Maltese Falcon is another example. The character was explicitly gay in the novel upon which the film is based, but in the 1941 movie, director John Huston had Lorre play a feminized soft-spoken man, suggestively stroking a distinctive cane. Since he was a villain, the inferences about his sexuality were passed by the censors.

‘Queer coding’ is the practice of using tropes to refer to a character’s sexuality without confirming it. Marlene Dietrich and Greta Garbo were two actors dressed in men’s clothes in the movies who kissed women on the lips with nary an eyebrow raised – Dietrich as a cabaret singer in 1930’s Morocco and Garbo in 1933’s Queen Christina, the 17th-century queen who never married, dressed as a man and was thought to be a lesbian. In the film, when she is exhorted to marry as she couldn’t die an old maid, Garbo answers, “I have no intention to. I shall die a bachelor.” Both actors were bisexual in real life, Garbo going to great lengths to hide her sexuality, even giving up her career in order to preserve her privacy.

Other examples are Doris Day singing “Secret Love” dressed as a man in Calamity Jane, and Montgomery Clift and John Ireland comparing each other guns in one scene in Red River, the subtext obvious.

The Hays Code was further tightened in 1934 when the Catholic Church started rating movies and threatened boycotts against those that were considered morally abhorrent. Joseph Breen was put in charge of censorship and pored over every script, changing words, scenes, even plots before he approved it. In The Celluloid Closet, Russo explains, “The Lost Weekend, a novel about a sexually confused alcoholic, became a movie about an alcoholic with writer’s block. The Brick Foxhole, a novel about gay-bashing and murder, became Crossfire, a movie about anti-Semitism and murder.”

In 1955, Rebel Without a Cause featured the first gay teenager played by Sal Mineo, himself an out gay actor, who has a coded relationship with James Dean’s character.

Author and screenwriter Gore Vidal explain in The Celluloid Closet, “You got very good at projecting subtext without saying a word about what you were doing.”

As the screenwriter of 1959’s Ben-Hur, Vidal convinced director William Wyler to allow him to hint at a past gay relationship between Ben-Hur and Messala. In the scene where the old friends are reunited, Stephen Boyd as Messala was instructed to play it as though he were still in love with Ben-Hur. Charlton Heston was left ignorant of his motivation as Wyler thought he’d “fall apart” if he were told. “I’ll take care of it,” he told Vidal. “Don’t say anything to Heston.”

In Stanley Kubrick’s 1960 Spartacus, a scene where Tony Curtis as Marcus’ (Lurence Olivier’s) servant bathes him in a homoerotic way was cut from the film. 1958’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof was cut multiple times to remove any trace of homosexual inclinations from Brick (Paul Newman) for his friend. In 1959’s Suddenly Last Summer which Vidal also adapted for the screen, the villain of the piece, a homosexual, is only shown in flashback and his face is never seen, a result of censorship battles.

In comedies, it was easier to portray homosexuality. In Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, Jane Russell is ignored by all the gay bodybuilders in a gym as she sings “Ain’t There Anyone Here for Love?” Rock Hudson pretends to be gay in order to ingratiate himself with Doris Day in Pillow Talk – an actual gay man playing a straight man onscreen pretending to be gay.

With the rise of television and the fear of dwindling movie audiences, The Celluloid Closet explains how filmmakers took advantage of the weakened Code to portray homosexuality directly onscreen. In 1962, Advise and Consent, directed by Otto Preminger, tells the story of the blackmail of a US senator over a past homosexual affair. And in 1961’s The Children’s Hour, based on the Lillian Hellman play and directed by William Wyler, two teachers are accused of a lesbian relationship by a student. The teacher who is actually a lesbian, played by Shirley MacLaine, kills herself. The actress regretted doing the film and explains why in the documentary. “We might have been the forerunners but we weren’t really, because we didn’t do the picture right,” she says, adding that the subject of homosexuality was never even discussed during the filming. In 1968, The Detective, with Frank Sinatra in the title role, takes on a murder case that involves homosexuality, portraying those involved as desperate and mentally ill. In all these films, homosexuality was treated as shameful, informing the perceptions of the audiences watching.

Arthur Laurents, the well-known gay screenwriter (Rope, Bonjour Tristesse, The Turning Point, The Way We Were) has this to say in the documentary: “You must pay. You must suffer. If you’re a woman who commits adultery you’re only put out in the storm. If you’re a woman who has another woman, you better go hang yourself. It’s a question of degree. And certainly, if you’re gay, you have to do real penance – die.”

Finally, there was a movie that showed homosexual relationships where the men were neither psychopaths or sadistic killers or mentally defective. The Boys in the Band, directed by William Friedkin in 1970, showed normal gay life in all its colors. The Los Angeles Times reviewer called it “unquestionably a milestone,” but the paper refused to run ads for it.

And in 1972 then there was Bob Fosse’s Cabaret (adapted from gay iconic writer Christopher Isherwood’s Berlin Stories) which, says author Armistead Maupin in The Celluloid Closet, was “the first film that really celebrated homosexuality… For me it embodied the very life I was beginning to live in San Francisco, one in which there was no onus placed on homosexuality.” Michael York’s character was gay and treated as normal.

But for every step forward, there were always a few steps lost. The Celluloid Closet shows a montage of different movies through the 70s and 80s where the word “faggot” is casually flung around, not having the same loaded implication of the n-word.

Films like Cruising, The Fan and Windows all had gay characters who were murderers. But for the first time, the gay community fought back, protesting the negative portrayal of gay characters and disrupting the filming of Cruising, during the summer of 1979 in Manhattan, as director William Friedkin and star Al Pacino recalled.

1982’s Making Love, directed by Arthur Hiller, had two gay characters in the lead roles about the attraction of a married man to another man, but casting was difficult as no actor would take the roles. Finally, Harry Hamlin and Michael Ontkean took the jobs against the advice of their advisers. The 20th Century Fox executive who watched the film before it was released (it was greenlit by the previous regime headed by Sherry Lansing) walked out of the screening calling it “a goddamn faggot movie.”

It was only when Philadelphia was made in 1993, winning Tom Hanks an Oscar, that the fear of playing gay characters diminished. Hanks confesses, “My screen persona is pretty much non-threatening . . . so this idea of a gay man with AIDs doesn’t have to be scary. You don’t have to be threatened by this man’s presence because little Tommy Hanks is playing the role.” He sees the message of the movie as gay or straight, “love is spelled with the same four letters.”