- Film

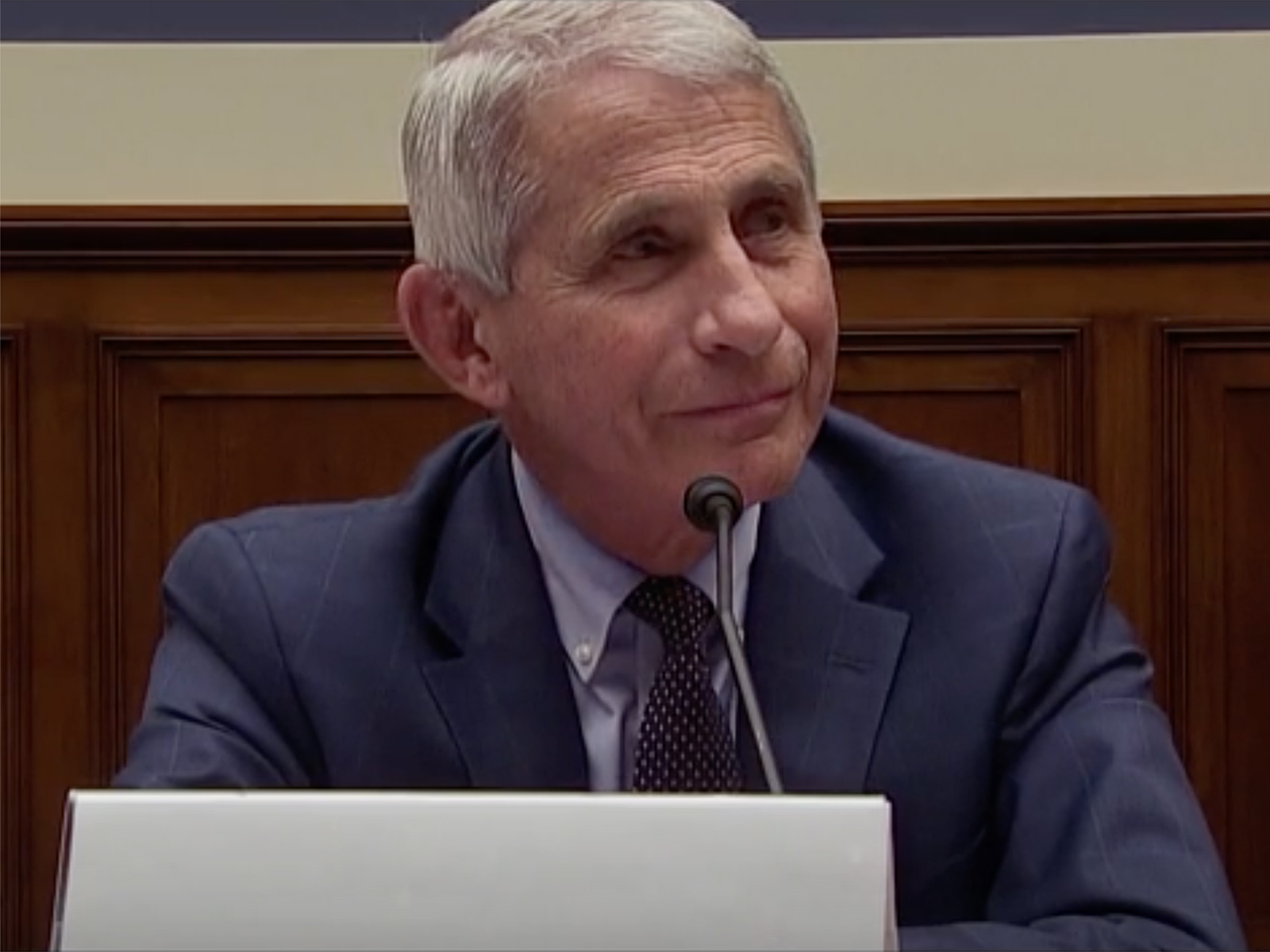

Docs: Fauci (2021)

The opening credits of the new documentary Fauci alternates between footage venerating Dr. Anthony Fauci and heated news and radio clips suggesting the world-renowned immunologist and Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases should be fired, jailed, or even executed, and have his head “put on a pike to serve as an example to other bureaucrats.”

This segment ends with footage of Fauci, on his cell phone in a car, attempting to find the proper security gate for entrance to a meeting. At once sad and pulse-quickening, this deft framing of the shocking degree to which an unelected scientist became arguably the chief receptacle for such intense public feeling during a scary pandemic sets the table for an engrossing examination of his professional life.

Fresh off its world premiere last week at the Telluride Film Festival and receiving a September theatrical release only at venues where proof of vaccination and masking measures are implemented, Fauci will make its streaming debut on Disney+ in October. If the movie feels somewhat incomplete given the unresolved nature of the pandemic and the fact that, especially in America, people have embraced at least two different realities about COVID, Fauci still lands as an interesting and moving portrait of the higher call for public service – of someone with inherent decency and formidable intelligence grappling with how to offer appropriate counsel during some of the most difficult circumstances imaginable.

Directed by Emmy Award winners John Hoffman and Janet Tobias, Fauci (for which its subject neither received any compensation, nor editorial control) was shot in secret over the last two years. After dispensing with just a brief side serving of early biography, detailing more how Fauci met his wife Christine Grady than any of his adolescent years, the movie then sets up its two main narrative pillars – the AIDS crisis which exploded across the United States in the 1980s and the COVID-19 pandemic, and Fauci’s work in and response to both.

Editors Brian Chamberlain and Amy Foote do an exemplary job of ducking back and forth between these stories, finding both common ground and points of difference from which to draw a comparison. Other important, complementary narrative strands – such as the moral imperative of the $15 billion PEPFAR program under President George W. Bush, and Fauci’s work during the Ebola crisis in 2014 – are smartly interwoven, providing further ballast to this smartly considered structure.

Much can, and will, be made over what Fauci is definitely not: namely, a broadside against former American President Donald Trump, and the commingled disinterest, incompetence and moral neglect of his response to the COVID crisis. This isn’t to say that the film completely ignores the elephant in the room. When asked his initial impressions of Trump and his feelings about the previous administration’s response, Fauci sighs and replies, “Yikes… how deep do you want to get?”

The harshest critics of Fauci (who would likely never watch this film in the first place) could argue that it embraces a flattering portrayal of him. But that would ignore that it does so only by highlighting his empathy, as well as his willingness to continue learning – not merely intellectually, but also personally and socially.

Time and time again, the movie portrays how Fauci didn’t cut off those who questioned or criticized him. This culminates in footage of a 1980s speech Fauci gave in which he talked about misconceptions between scientists and ACT UP activists, and what they had to learn from one other. This commitment to bridging the gap between institutional and advocacy communities, acknowledged in the movie by several foes turned friends, is an important precursor to changes now taking place elsewhere in society.

It can also be readily seen as emblematic of a core quality one would want in a leader, a trait thrown into relief by Trump’s diseased politicization of COVID and needless antagonism of the media as if the virus itself were somehow the invention or fault of reporters asking questions about it for the sake of public health and safety. Fauci’s comportment is not the empty embrace of “both sides-ism” merely for the sake of dialogue, but rather an example of his humanistic commitment – the dogged pursuit of helping as many people as possible, without denigration of those who are scared or confused by or hostile to new information.

“I’ve been made a villain because I represent something which people are uncomfortable with – the truth,” Fauci says early in the film. Later, in reflecting on the pitched confrontation that eventually helped to build consensus and turn the tide in the AIDS crisis, he states that he thinks the United States will get through COVID despite but not because of our differences, and the vast divisiveness in the country today. It’s moments of candor like these that cast an uncertain shadow over our shared future and give Fauci a deeply melancholic streak.