- Film

Docs: “Mama’s Boy” Traces Activism to Lessons of Absorbed Resilience

The term “mama’s boy” used to be a pejorative, loaded with connotations. It could signify anything from a man’s relationship deemed unhealthily close with his mother, to a sensitivity out of step with conventional societal views on masculinity, to a general “failure to launch” into adulthood. In some circles, it could even serve as a veiled slur against the perceived sexual orientation of a young adult male.

As the title of director Laurent Bouzereau’s documentary about Oscar-winning Milk screenwriter and social activist Dustin Lance Black, however, it takes on additional dimensions, helping to lend added poignance to this slice of personal monologue storytelling. Adapted from Black’s own 2019 memoir “Mama’s Boy: A Story from Our Americas,” the film, available now on HBO Max, is a study of both Black’s personal journey and the overall lessons of incredible resilience he absorbed from his remarkable mother.

Raised in a conservative Mormon home in Lake Providence, Louisiana, Black’s mother (known as both Roseanna and Anne, and at times referred to as each in the movie) was the seventh of nine children, and contracted polio as a young child. She endured brutal surgeries and years of hospital visits and was told she would be unable ever to have children.

Anne, however, refused to be defined by the lingering aftereffects of her disease. Though reliant on crutches for the rest of her life, she got a college scholarship and managed to craft a successful career for herself while also raising three sons, Dustin, his older brother Marcus, and younger brother Todd.

Anne also survived two turbulent marriages, which additionally left an imprint on her boys. Black’s biological father, Garrison, was a traveling salesman and serial philanderer who had trouble holding down a job and would eventually be caught having sex with his first cousin. Anne’s second husband, Merrill Black, initially presented himself as a savior, in a marriage in large part arranged by the Mormon church. But in short order he revealed himself to be an unstable and abusive monster who at one point even tried to kill Anne. Much-needed stability would finally arrive in the form of stepfather Jeff Bisch, though a family move to Salinas, California, put Marcus onto a troubling path.

Through it all, Dustin struggled with his identity, even as he gravitated toward storytelling and the entertainment industry. After high school he would move south to Pasadena, and in 1994 eventually win acceptance into the UCLA Film School, setting him on a path toward a career as a writer — first for television (Big Love), and then moving to the big screen to tell the story of San Francisco politician Harvey Milk and other marginalized figures, as in Rustin, the upcoming biopic of civil rights organizer Bayard Rustin.

While overwhelmingly rooted in family, Mama’s Boy also devotes a significant portion of its running time to Black’s bridge-building activism, which took shape in the wake of his February 22, 2009, Oscar acceptance speech. More than a year before the “It Gets Better” project would gain prominence online, Black used this live-television moment on the international stage to speak directly to gay and lesbian youth being bullied or ostracized.

After the telecast, Anne held him to actual action — reflecting a reversal of her attitude from when her son had first came out to her at the age of 21. Black would go on to play an instrumental role in helping to overturn California’s Prop 8, a 2008 ballot measure intended to ban same-sex marriage.

The “coming out” portions of Mama’s Boy aren’t its most significant passages, but they do offer some illuminating insights by way of shared truth. It’s particularly eye-opening (probably especially for heterosexual viewers) when both Black and one of his best friends, Ryan Elizalde, recount Black’s hostile reaction to Ryan’s coming out as gay — almost badgering him into revealing it so that Black could then flip out on him. In unpacking his own complicated relationship to the fundamentalist religious dogma under which he was raised, it’s a fascinating and incredibly moving snapshot of the toxicity of closeted existence, summed up when Black reflects back on his mindset at the time by simply saying, “You want to know the recipe for treating people really poorly? Hate yourself.”

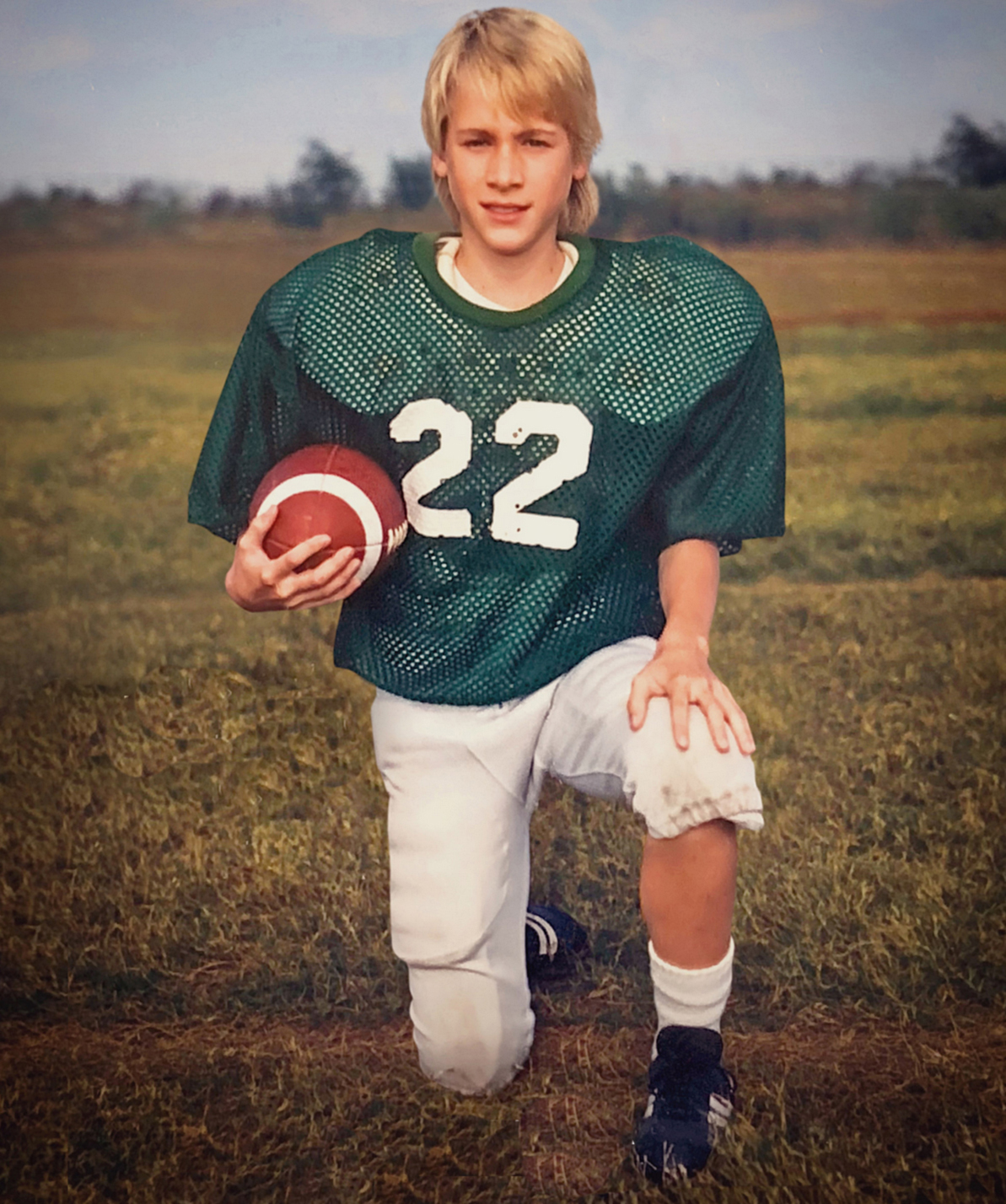

Bouzereau (Natalie Wood: What Remains Behind) is a capable director with an unobtrusive touch, and he is here smart enough mostly to cede center stage to Black, as an interviewee and as the movie’s narrator. Bouzereau recognizes this material for what it is — a universal story of familial love and reconciliation channeled through a deeply personal tale — and uses old photos and videos to support this telling. Composer Raphaëlle Thibaut, meanwhile, contributes a score that is at once elegiac and wistful, faintly recalling that of The Bridges of Madison County.

Overall, Mama’s Boy is an affecting tribute to a mother’s courage and determination, and a portrait of the strength she instilled in her son to fight for his beliefs. It’s also a celebratory reminder of the power of listening to stories in shared spaces — witnessed in everything from Anne’s connection with Black’s gay friends during a surprise trip to Los Angeles for her son’s graduation, to Black’s own re-embrace of his extended family in Texarkana.

As Black himself says near the end of the film: “Politics is important, because it builds the systems we live within. But how can politics be good if we don’t put families first, and get in the same rooms with people with whom we have history, but might disagree?”