- Film

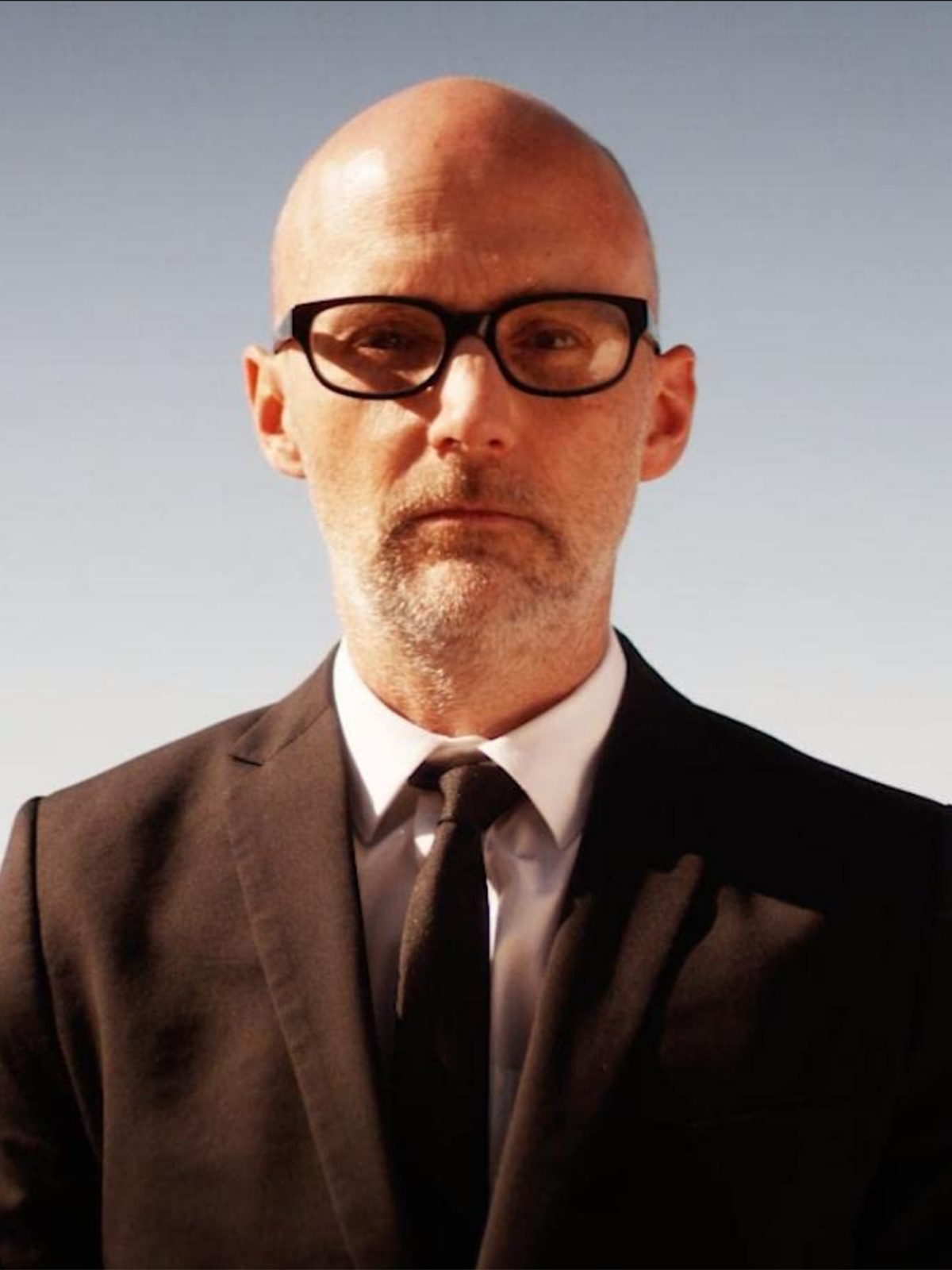

Docs: Moby Doc (2021)

An idiosyncratic and engaging work that finds a way to mimic the at-odds kineticism and inherent melancholy present in its subject’s music, Moby Doc serves as both a bouncy nonfiction exploration of pioneering electronica artist Moby and a document of therapeutic self-examination.

Directed and edited with considerable aplomb by Rob Gordon Bralver, the movie holds at bay some of the (very present) clichés of rock star bio-docs, from drug abuse to suicidal ideation, by way of an atypical structuring and the use of various narrative end-arounds and filters. The result – playful but always ruminative, and also at times lacerating in its emotional forthrightness – leans into youthful ambivalence, mental health struggles, addiction, and trauma, making Moby Doc as easy a recommendation for folks who don’t know its subject’s oeuvre as those who consider themselves fans.

Born Richard Melville Hall in 1965, Moby grew up poor. After his father, an alcoholic Columbia chemistry professor, killed himself in a car crash when Moby was two, several years of squatting and a revolving door of his mother’s boyfriends ensued. The pair would eventually move in with his grandparents in Darien, Connecticut, where the overwhelming affluence of the rest of the tiny community fed already present feelings of inadequacy and depression.

Weaving together rare archival footage, home videos, and material from YouTube, parts of the film dutifully check all the boxes of Moby’s professional life and public profile. This includes everything from the 1991 remix of “Go,” which incorporated a string sample of “Laura Palmer’s Theme” from Twin Peaks, that made him a star in Europe and provided his first taste of financial stability, to his longstanding and committed work as an animal rights activist.

Naturally, though, it’s the aforementioned chaotic and unmoored family life that most informs Moby Doc, interestingly pushing past comfortable bromides, and giving them shading and depth. Moby doesn’t merely “like” animals; he explains how, from his earliest memories, they provided the only calming and safe presences in his life, in contrast to the tumultuousness of his family relationships, so he came to view animals as trustworthy and most people as not. Similarly, music didn’t just “save his life.” Years before he would ever seek therapy, it was an act of self-care where he could try to “take [his] fear and make it interesting, take the confusion and make it beautiful.”

The arc of Moby’s career is interesting to consider when examined alongside the advent and rise of social media, and the degrees to which certain celebrities have leaned into image control and biographical mythmaking. Moby’s biggest commercial success, 1999s 12-million-selling Play, came about before the Internet’s takeover of day-to-day life. By the time social media got its hooks into Millennials, he was, at least in mainstream culture, somewhere between a curio and a punchline – still releasing music, but notably lampooned in everything from Eminem’s scathing “Without Me” to Get Him to the Greek. Moby was incongruously known for rock ’n’ roll overindulgence and substance abuse, while at the same time serving as the go-to target for seemingly all vegan and bald jokes. There was a slightly off desperation to his entire persona.

With the settled perspective of maturity and age, Moby Doc embraces the notion that you can either expend a lot of energy running from the truth of one’s own pain and shortcomings, in a misguided effort to be “cool,” or you can own it and foreground it. Moby here leans into the latter, candidly assessing the damaging effects of his own fitful obsessions with fame, and a one-time focus on every message board insult slung his way. (One brief segment, with the refrain “Nobody listens to techno” repeated over and over, even provides an informal nod to the real-world sting of Eminem’s aforementioned diss track.)

Bralver, an editor on docs like Our Vinyl Weighs a Ton and Gore Vidal: The United States of Amnesia has over the past few years collaborated with Moby on a number of music videos. Owing to that, he obviously has the trust of his subject. But his sophomore feature directorial effort is more than the mere product of accumulated goodwill. By way of contrast, Miss Americana, Lana Wilson’s genteel documentary about Taylor Swift, shed considerable light on Swift’s creative process and political awakening. But it also clearly made concessions in its portrayal of that superstar musician. Moby Doc, while obviously a work in which Moby has considerable direct artistic input (he even takes a co-writer credit with Bralver), features no such trade-off. As such comes across as a more genuine portrait, foibles and all.

Again, and again, the movie finds interesting ways to frame and tell its story. Portions find Moby wandering a bodega or desolate urban landscape, holding forth in a monologue over the phone with a party never seen; others unfold in a shared conversation between Moby and filmmaker David Lynch, or artist Gary Baseman; others still involve staged therapy sessions in which collaborator Julie Mintz sits in as a psychologist. There’s animation, too, and even bumper segments featuring mouse puppets crafted by Moby. It may sound scattershot, but there’s a creative coherence to the assembled sum total of these disparate parts.

In its final 15 minutes, the film’s energy flags just a bit; it feels padded here, or at least uncertain about quite how to steer the ship into the harbor. But Moby Doc is overall absorbing, and its presentation and mixing of the documentary’s musical sequences, including Moby sitting in with the Pacific Northwest Orchestra, is skillful and illuminating. In intercutting a plaintive acoustic performance of Moby’s sorrowful “Porcelain” with footage of its ecstatic reception by a crowd of thousands at a nighttime festival, Bralver captures, with economic profundity, piercing truths about how some of the most gifted songwriters come to process their despair – seeking to box up intensely personal trauma, but still hoping quietly that heartache will chart.