- Film

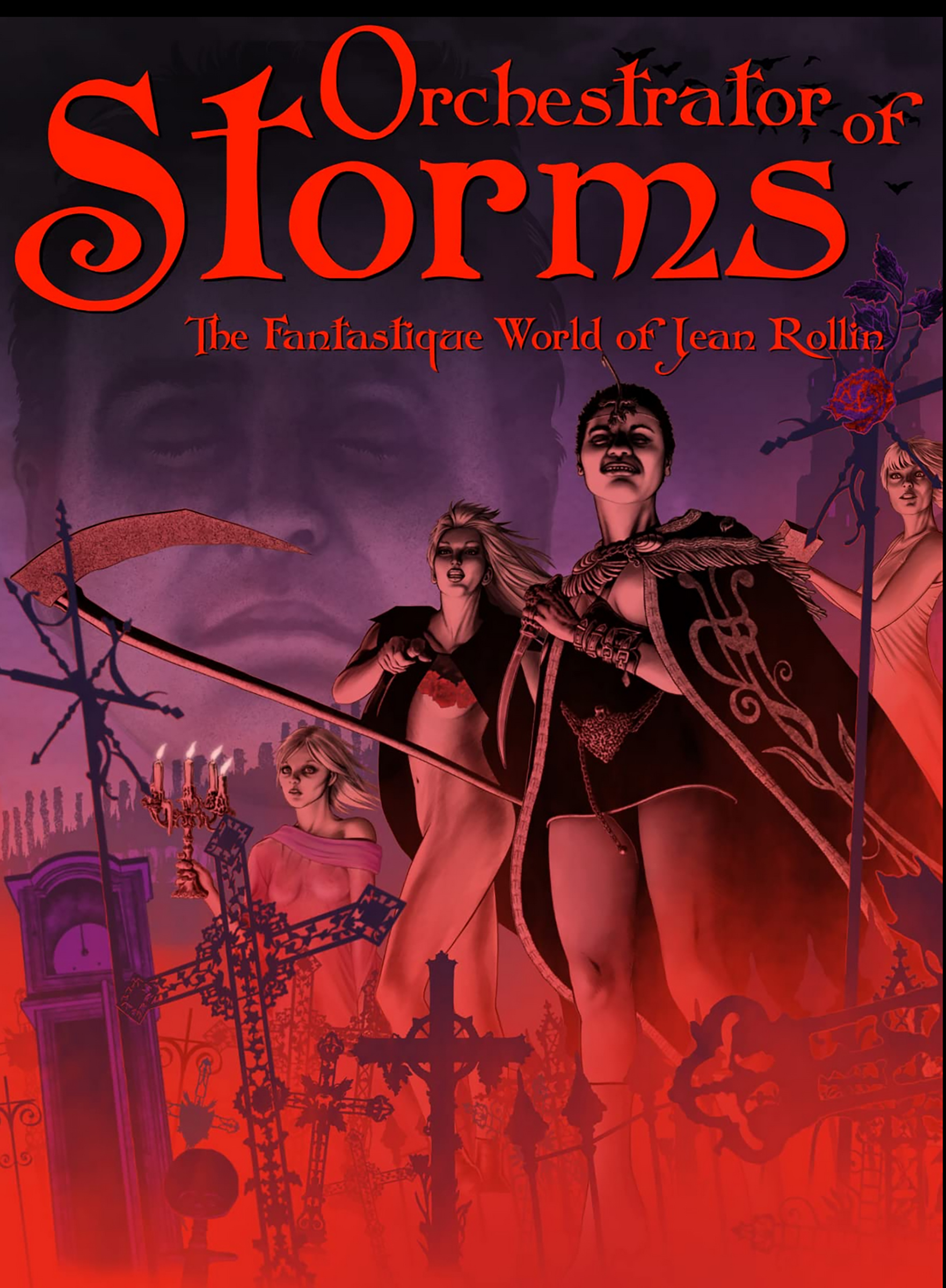

Docs: “Orchestrator of Storms: The Fantastique World of Jean Rollin”

For those unversed in the world of Jean Rollin, Orchestrator of Storms is an informative documentary about one of Eurocult cinema’s most unique voices. Rollin, who died in 2010, was a French film director, actor, and novelist known for his work in the fantastique genre.

Jean Rollin achieved cult status in niche English-speaking circles from his vampire classics Le Voil du Vampire (1968), La Vampire Nue (1970), Le Frisson des Vampires (1970), and Requiem pour un Vampire (1971). His other works include La Rose de Fer, Lèvres de Sang, Les raisins de la Mort, Fascination, and La Morte Vivante.

Filmmakers Dima Ballin and Kat Elliinger spoke on the phone about their collaboration on Orchestra of Storms: The Fantastique World of Jean Rollin. Through their film, they opened a window into the mind of this great misunderstood artist.

How did Orchestrator of Storms come about? Where did your passion come from for this subject?

Dima: I’ve always liked Rollin’s films. I can’t explain why. They just touched me in a particular way. This project came about quite by accident. Kat pitched it to Arrow Films as a short documentary but we went way overboard and made a feature film out of it because we just felt strongly about it. It’s almost like it had a life of its own.

Kat: I have spent the majority of my career as a film writer focused largely on both Gothic and Eurocult. Rollin is a big part of that. I’ve written and spoken about his work in a professional capacity for a long time now.

Why Jean Rollin? Was there one film that struck a chord with you that sparked your interest in developing this documentary?

Dima: Well, the two films I love the most are Fascination and The Iron Rose. They’re just really sublime in a way that’s hard to explain.

Kat: It wasn’t any particular film. My obsession with his work has always been a broad career sense, rather than individual titles.

How did you decide who you wanted to invite to contribute? Did you have an initial wish list of participants in mind?

Kat: A lot of the people in the film, in terms of the film scholars, are peers (some even friends too) of mine, as Eurocult, and Rollin’s work in particular. I was clear from the start I wanted people who knew or had worked with Jean. It was important to try and convey who he was as a person, which was the heart of the film. As he’s, sadly, no longer with us, we needed people who had that special personal connection to both him and his work.

What did you learn about him that surprised you?

Dima: How much he went through to get his films made. He’s one of those maverick filmmakers like Orson Wells or John Cassavetes. I keep mentioning those names in interviews because even though artistically he’s totally different from them, of course, he had this maverick sensibility. He just wanted to make films no matter what. He made films no matter how sick he got, no matter how little money he had, no matter if people wanted to murder him, which I think happened when he made his first feature film. There was a riot. We used his autobiography as kind of a research foundation for this film. Aside from his childhood, he has surprisingly little, if anything, about his personal life. He got married at some point. He had a wife, he had two children. None of that is mentioned.

What was it like working with his family?

Kat: I was in contact with Jean’s son Serge the whole time we were making the film. Without his help we couldn’t have done it the way we did. He was very helpful in providing photographs, background information, leads on contacts and such.

What do you think makes Rollin so unique?

Dima: Well, his vision is unique, it’s very personal. Even though he made films just for money, like porn, his personal films are really personal. I mean, they’re kind of divisive. You either like them or you don’t like them. I don’t know too many people who started out not liking them and then liked them, although I’m sure that’s happened.

Kat: To me, there is nobody like Jean Rollin, not in the field of Gothic horror or Eurocult in general. Rarely do you ever see anyone else drawing from the same specific art and cultural history well that he did, especially when it comes to his relationship with a particularly French decadent tradition, French symbolism, and the way he used the fantastique, rather than a pure gothic tradition.

What would you say is the biggest misconception about him?

Dima: That he exploited women. He didn’t exploit women. Women loved him. He was always surrounded by women. His actresses loved him, for the most part. He definitely did not exploit women, even though he liked to photograph a lot of naked women.

This is an interesting point. Kat, what are your views on this? Was that a misconception you were aware? Did this ever impact conversations you had when you would share your passion for Rollin with people?

Kat: It’s no accident that Rollin’s work has consistently drawn women as fans. The women in his films, especially when it came to the vampire, were a far cry away from what you saw in commercial film. They were often empowered. He used things such as the chthonic feminine, or the Sadeian feminine (the latter which feminist writers such as Angela Carter have explored in depth as pro-feminist in a sex-positive sense), which has a certain attraction for women like me. But, because he’s not commercial in a traditional sense, people often write off his films as too arty, not horror enough, too sexual. I’ve spent years hearing him being written off by horror fans in general but I’ve continued to champion him despite that. I have a very personal connection to his work in this respect.

Can you talk a little about your background? How did you get into the business? Is this something you always wanted to do?

Dima: I always wanted to make films. I’ve never had a chance to before, for personal reasons. I have a lifelong mentor named David Kleiler who, basically, taught me how to see film, how to interpret film. I’ve been with them since I was 15. He just died about four years ago. That’s really it. I founded Diabolique Magazine, co-founded the Boston Underground Film Festival with David, actually. Everything I’ve always done has kind of slowly led me to this point. I’m going to be making fiction films next.

Kat, what about your background? As this is your first feature, how did you find the shift from writing to film-making?

Kat: Dima and I have worked on a number of features. While I am usually credited as writer/producer, our process is so intertwined that it’s actually not ever entirely that clearly defined. This time it just felt I should take a co-director credit, as it was our longest and most involved project so far. But all the films I’ve made have been film-related. So, for me it’s not so much about making films themselves, but a way of widening the way in which I get to explore film history.

You said earlier that someone wanted to murder Rollin. Can you just talk a bit about that?

Dima: Well, I was being slightly facetious. Basically, there was a riot during the showing of his first film, the Rape of the Vampire. People were throwing bottles. They chased him out of the theater with the intent of really hurting him. It was part of the riots that were taking place all over Paris, actually, because of the striking workers. It was unfortunate timing, as it was in the middle of the May ‘68 riots.

What would you like audiences to walk away with after watching the film?

Kat: I just wanted to make the film for myself and his fans because it felt like it needed to be said for us, by us. His story needed to be told. I would like it to change people’s perception of him. He deserves that. And even if they still don’t like his films, maybe they will understand him as a filmmaker, someone who just gave his entire life to the cinema he wanted to make. Fans can relate to that.