- Film

Docs: Time (2020)

Time, a gripping, touching, and relevant film, is one of the five nominees for the 2021 Best Documentary Feature Oscar. It centers on one extraordinary woman, Sibil Fox Richardson (nicknamed Fox Rich), as she fights boldly and relentlessly for the release of her husband Rob serving a long prison sentence.

Director Garrett Bradley’s documentary (available on Amazon Prime Video) highlights the lifelong effects that mass incarceration has, not only on the imprisoned, but also on the families they leave behind.

The film world-premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, where it won the U.S. Documentary Directing Award, making Bradley the first African American woman winner in that category.

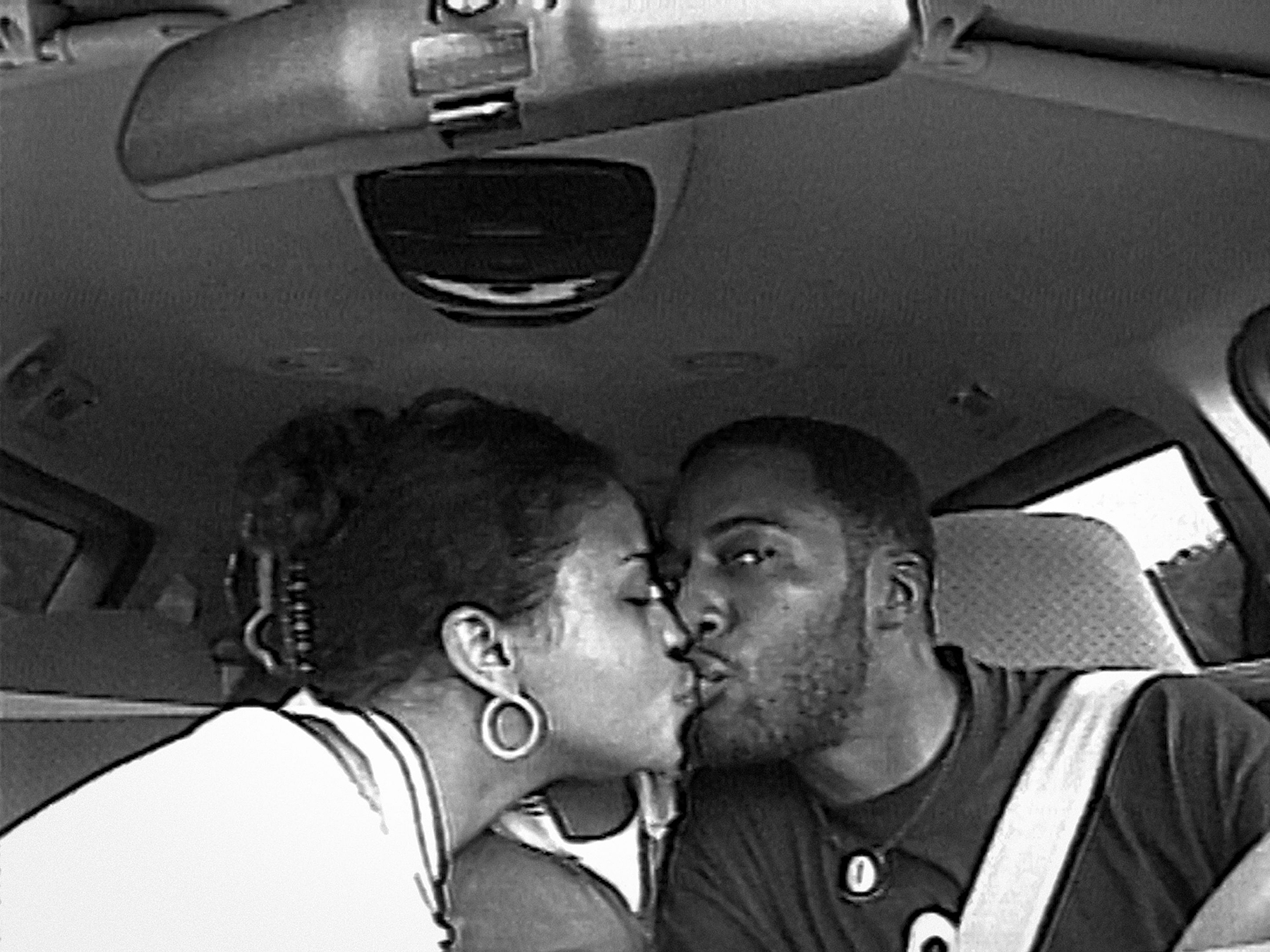

Bradley met Rich in 2016 while working on her short Alone, a New York Times Op-Doc. Initially she intended to make a short, but when shooting wrapped, and Rich gave Bradley mini-DV tapes, containing more than 100 hours of home videos recorded over the previous 18 years, she decided to make a feature.

Rob was sentenced to sixty years without parole in Louisiana State Penitentiary for a botched bank robbery that he and Fox had committed together in 1997. Fox served three and a half years for her role as the getaway driver.

Rich recorded hundreds of hours of home videos while her husband was in prison, so that he could see how his children grow up – without him. At the time, she didn’t know that the intimate footage would serve a greater purpose and bring awareness to the devastating effects of incarceration.

Time demonstrates how people of color face sentencing disparities that are disproportionate to the offense. As Rich says: ‘When you walk into the courtroom, the scales are already unbalanced when they see your skin complexion. Black people are sentenced longer than their White counterparts and far more aggressively.’

According to the Sentencing Project, people of color make up 37% of the U.S. population but 67% of the prison population. The research and advocacy center notes that in general, ‘Black men are six times as likely to be incarcerated as White men.’

The documentary has taken on new meaning after the reemergence of the Black Lives Matter movement and protests over systemic racism and police brutality. Fox knows this battle all too well: She has raised six Black sons while fighting for the release of her high school sweetheart. ‘My story is the story of over two million people in the United States that are falling prey to the incarceration of poor people and people of color,’ she says.

Bradley combines the intimate video diaries that Fox recorded over two decades with present-day footage, showing her evolution from a young mother to a resilient feminist and political advocate. Her main goal was to show ‘how the system was so unequivocally embedded in every part of the family’s life.” There’s always been an element of suspense due to the unknown factors and long production process. ‘I was very emotionally invested in Rich’s story, but there was no sign of what the ending would be,’ Bradley said. ‘I hoped to illustrate that one really doesn’t know where you stand in the grand scheme of things, because the justice system is a very vague, intentionally complicated, and bureaucratic process.’

Despite tirelessly fighting for her husband’s release and her family’s reunion, Fox doesn’t consider herself an activist, but rather an abolitionist. ‘Having served time in prison allowed me to see that prison didn’t just reflect what we read in the history about slavery, it was the same thing,’ Fox says, emphasizing the notion that “mass incarceration is slavery.’

Fox wasn’t the only one who evolved over the course of the documentary. The juxtaposition of footage shows the couple’s children going from kindergarten to graduate school, highlighting all that time that Rob had lost with his sons.

In the process, we get Rich’s entire family, and how inspired its members are by their courageous mother who’s determined to keep her nuclear unit safe, whole, and unified. There’s a realistic sense of the price of tough daily existence, defined by growing up without a father – or any other significant male role model. ‘My family has a very strong image but hidden behind that is a lot of hurt, a lot of pain,’ says their eldest son Remington, who remarkably went on to graduate from Meharry Medical School of Medicine.

The documentary concludes with the Rich family being reunited in September 2018. After 21 years. Rob was granted clemency and released from prison wearing a ‘Never Give Up’ T-shirt.

Upon his return, the Rich family held a ceremony to burn their cardboard cut-out of Rob, a birthday gift their children got for Fox to signify, as she says, “that he is in space with us.’ ‘I said that once I went to prison, I would stand like a man,’ Rob says at his welcome home event. ‘That I would speak truth to falsehoods, that I would finish strong and God knows that I would never give up, because y’all are worth fighting for.’

Rich refuses to treat her husband – and herself – as symbols of oppression. Instead of objectifying her case, she and the director emphasize the particulars of her story, while allowing viewers to draw more generalized conclusions.

The couple’s fight for justice is far from over, which gives the film an extra dimension of relevancy. They created the Participatory Defense Foundation to teach other inmates and families how to participate in their own defense and how to influence the outcome of cases.

In its bold approach, Time delivers a powerful broadside against the flaws of the American justice system, raising questions about dysfunctions of incarceration for the individual prisoners, their immediate family, their community, and society at large.

Displaying a dazzling formal style, the film was shot on a Sony FS7 camera in black and white. The resulting crisp images are based on graceful angles and fluent compositions, the kinds of which are seldom seen in a debut feature. The remarkable score and sound design are made up of original pieces by Jamieson Shaw and Edwin Montgomery, as well as music by Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou, recorded in the 1960s.