- HFPA

Doing the Work: Eddie Muller, Film Noir Foundation

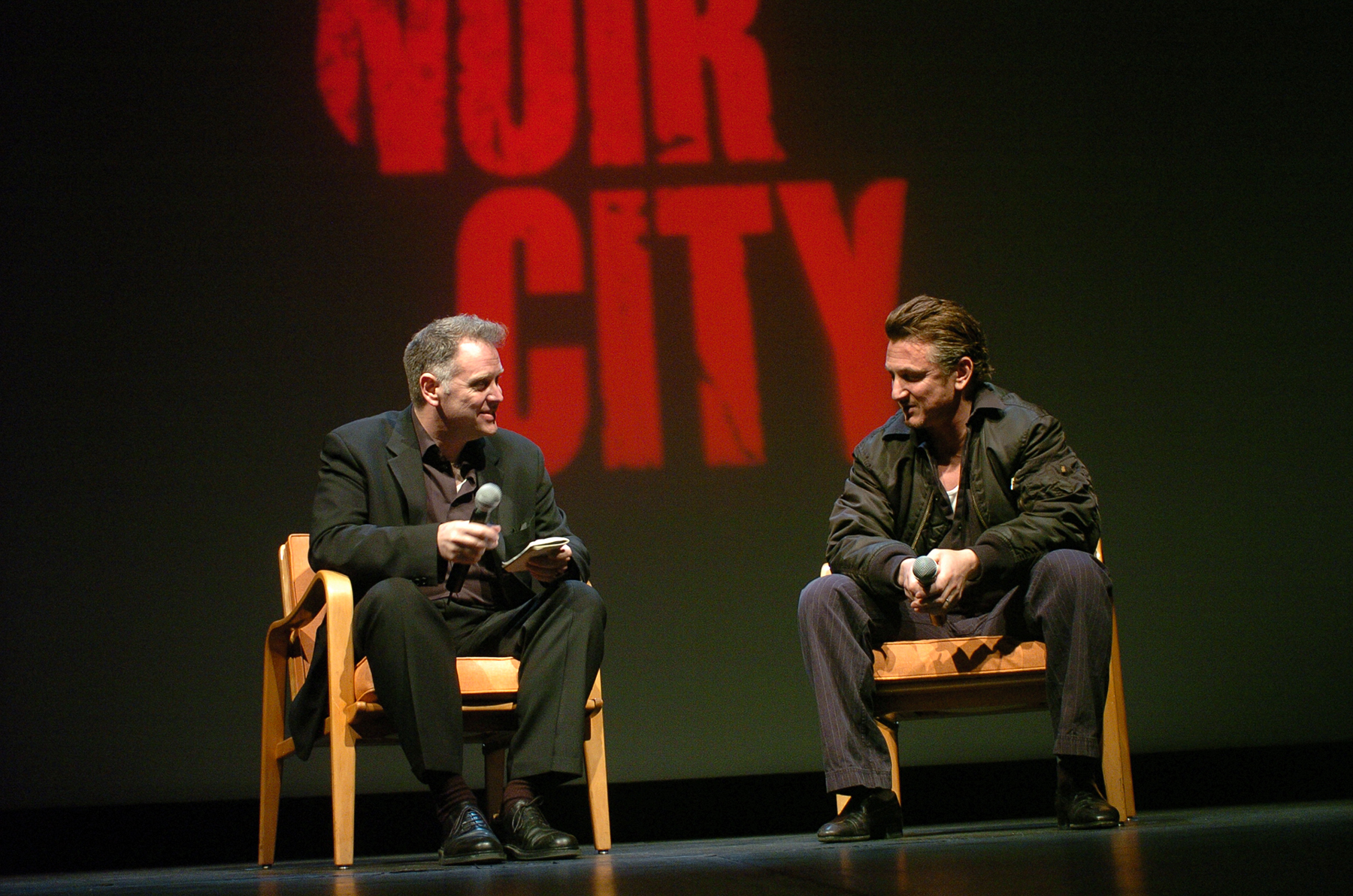

The 18th edition of Noir City, San Francisco’s staple film noir festival, took place at the historic Castro Theatre right before the pandemic hit, January 24 to February 2, 2020, amidst an electrified atmosphere filled with the enthusiasm of a consistently present intergenerational audience from the afternoon to the small hours of the morning. The festival’s success is owed in part to its founder’s presentations. A connoisseur of film noir, Eddie Muller placed each movie in its greater historical and artistic context, inducing a sense of learning, of begetting a worthwhile experience regardless of the film’s stand-alone value. Indeed, in the world of film restoration, cinema acquires yet another dimension: It documents an era. Which is why the HFPA has chosen to partner with the Film Noir Foundation on several restoration projects. Muller’s ability to connect the dots, derive knowledge, and preserve history is exceptional. Here’s why.

Becoming a patron of film noir was never his ambition. “I self-identify as a writer, that’s what I always wanted to be, that’s how I’ve earned a living – the only way I’ve earned a living,” he declared, then adding with a chuckle, “well, I was a bartender too”. But after having written a book on film noir – Dark City: The Lost World of Film Noir (1998) – he was invited by American Cinematheque’s Dennis Bartok to program a noir festival at Raleigh Studios in Hollywood. Since that time, “everything changed gradually”. Muller realized that until then the way he had been able to uncover these films was through fans who had taped them off the television, when there were no DVDs, and barely any VHS tapes with such titles. “I tapped into this network of people who were all do-it-yourself. So, when I was invited to program the festival it was very, very exciting because [we could] just show the movie! The real movie in 35 mm. And I was startled at how many of them were lost”.

The discovery of a lost world, meant a shift for Muller personally: “When I was 40 years old, it was all about how do I become the creative person I always wanted to be – write novels, make movies, all that stuff. Now I’m 61 years old and I take every bit as much pleasure in preserving the work of other people that would become lost, as I’ve taken creating my own work”. “It’s become very much a crusade for me,” he stressed. “I see something beautiful and I say, you can’t tell me we’re going to lose it. That’s not going to happen”.

From 1999 to 2004, Muller worked with the American Cinematheque in Los Angeles. It was his hometown, San Francisco, however, that gave him the certainty needed to officialize his mission in 2005. The first festival there in the same year filled the 1,400-seat capacity Castro Theatre. “It was like lightning in a bottle, people went nuts. And that was what enabled us to create the foundation,” he said. “I realized, oh my God if we can sell out the theater, we are actually making real money. That’s no joke.”

Even though he seemed to have hit a gold vein, Muller knew this was not going to be a commercial enterprise. “Quite honestly,” he explained, “I didn’t understand why I deserved that money”. Then, the idea came: “Let’s just take the money that we make and put it into a nonprofit foundation that finds more movies for us to show”. “This is a very significant point about what I do,” he added. “I realized I was a good public speaker and could talk a good game. I could make people excited to see these movies. But very few people do this taking the exhibition element first. Generally, the passion is put into restoring a film and then there’s a struggle to find the outlet. I came into this totally the opposite way. I created the outlet. I created the viewing experience. And I’m very proud of the fact that people would come no matter what I showed. 1,400 people would fill the theater for a movie they’d never even heard about. I cherish that I’ve been able to establish that level of trust and a spirit of adventure with the audience.”

Do all films deserve immortality, though? “I try not to judge based on my own subjective opinion,” Muller retorted. “That’s not my job. I’m not a film critic. My role is what I call a ‘noircheologist’, which is to preserve as much as I possibly can. There could be something historically significant about the film. It may be a low-budget film that tackles an issue that a major studio was afraid to deal with.” Such was the decision to restore – with the support of the Hollywood Foreign Press Association – The Argyle Secrets, a post-war film about the Nazi movement within the United States. “There were not too many films made in 1947 about that,” he chuckled. “Sadly, it still has a timely feel to it.” The most prominent criterion for preservation is that the “film says something about the culture either at that time or that it makes sense to see it now”. “It’s amazing, for example,” he added, “how many noir films resonate now because of the Me Too movement. People see that male behavior being exhibited in the movies. And I think it’s a great mistake to assume that the filmmakers were supportive of that attitude. A lot of these movies are showing women as the victims of what we now call ‘toxic masculinity’. We can clearly see a lot of them making a statement against psychotic male behavior. So, they have a timeliness and a resonance now”.

Ultimately, however, the answer to the question “why film noir” is an aesthetic one. “Film noir is the gateway drug to classic cinema,” Muller said emphatically. “If you want a 20-year old to watch a movie from the 1940s, you show them film noir – Double Indemnity, Out of the Past, The Killers. They’ll find other films from that era potentially corny but they won’t in film noir. Because it was America at its peak of style – the clothes were incredible, the architecture was amazing… the cars… and it’s also the moment when America started to decline.”

“All of a sudden,” Muller continued poignantly, “We lost our innocence”. “We realized we weren’t quite the culture we thought we were. There was a lot of corruption, the witch hunt suddenly erupted, people were blacklisted, artists were leaving the country… so we reached this culmination of creativity and then it all started to decline… the Hollywood studios… there was no longer a factory system producing all these great movies…”. “There’s a duality there,” he concluded, “that is important to understand why these movies were made when they were made … It’s a big part of the history”.

Yet film noir was not exclusively an American phenomenon. Even though Muller’s first book Dark City saw the genre as an “organic artistic movement within Hollywood,” that book was also the reason he discovered other such movements in other parts of the world, be it France, Argentina, Mexico, or India. “Film noir is supposed to be about all these negative things,” he said; “yet, personally, it has been this bridge that has opened up the world to me. Being able to meet other people and share my passion in other parts of the world has been without question the most gratifying part of what I do”.

When asked about the element that connects films into an international noir category, Muller’s answer is quick and ready: “Suffering with style”. “That’s glib,” he commented, “but not inaccurate because I believe those two things attracted people to the genre”. “There are people,” he went on, “who don’t respond to feel-good movies, but who appreciate the style, by which I mean not just the visuals, the camera-work, not just the wardrobe; the language is a style all of its own”. “You get to vicariously experience incredibly beautiful, sexy people doing the worst things – for your pleasure,” he laughed out loud.

“What I find interesting,” he went on, “is that these movies were perceived by some people in authority as dangerous. Their content was subversive in the fact that they were warning you that it’s not going to work out. Don’t trust authority. The system is rigged against you if you’re a poor person… and noir is the genre where the audience empathizes with characters [who suffer]. But the same films that once were perceived as dangerous to the culture, people now watch as comfort food. They find them reassuring…”. The way he sees it, film noir spoke of the realization of the loss of innocence in the nation, a process that was camouflaged by the rise of television and ended in 1963 with the assassination of Kennedy: “Any possibility of claiming that we are a moral culture was gone. We assassinated the President in broad daylight, everything was different after that … Our wheel turns but something is amiss because we keep repeating the same mistakes over and over again.”. Changing gears for a moment, but with the same sharp outlook, he added a more hopeful note referring to the Black Lives Matter protests: “I find a lot of optimism in what’s happening now. I had no idea that the American youth would take to the streets like this”.

For someone used to the duality of reality, to the coexistence of ‘good’ and ‘evil’, even the pandemic is an opportunity for growth. “We are asked to sacrifice for the good of the culture,” he offered. “I choose to think that there is a light at the end of the tunnel, and when we come out of it, those of us who have made the sacrifice will emerge in a better place. We’ll be better people. This is a lesson that we are being taught right now, and some of us are paying attention. And I look forward to a huge celebration when there is a vaccine when everybody feels completely at ease. I mean, I miss movie theaters but even more, I miss just going to a bar! Meeting people, talking shoulder to shoulder in a bar is my favorite thing in the world, and I haven’t had that since March 11”.

They call him “the Czar of Noir”, but after an hour of conversation with him, you realize that that title falls short of fully describing his mission to create a cultural phenomenon to spread from America throughout the world. “I figure I got ways to go still, I hope, but I gotta think who does this after me. It’s one of the reasons why a lot of my focus is on young people. I’ll approach them and engage them in a way that I hope inspires them. It’s an aspect about preservation that I think people overlook – the passion. The passion has to be transferred – to the audience, to your colleagues – it’s a very important part of the whole process”.

Anyone who watches films introduced by him can attest to the ardor of his commitment to noir and to its preservation. Ultimately, film preservation has a lot to do with an art form, but even more it has to do with cultural identity. And Eddie Muller, with his integrative, powerful mind, is aware that this is a matter of vital significance.