- Film

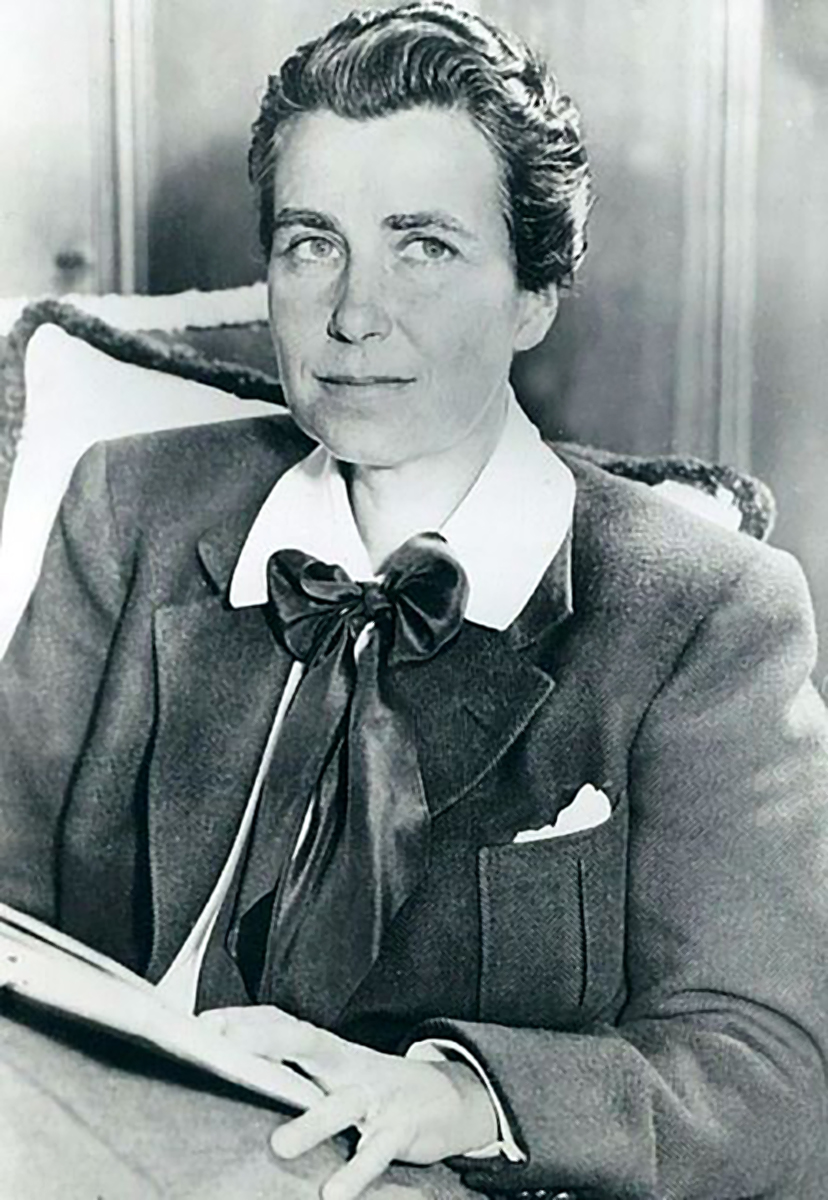

Dorothy Arzner: The Fiercely Independent Director

Dorothy Emma Arzner, born on January 3, 1897, in San Francisco, grew up in Los Angeles. Hanging out and helping out in her parent’s restaurant, the Hoffman Café in Hollywood, young Dorothy served and observed Hollywood’s elite of her day, mostly silent movie stars such as Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, Mack Sennett, and stage legend Sarah Bernhardt. But she was not particularly impressed by any of them.

At that time, the medical profession had more allure for her. She studied at the University of Southern California, worked in a surgeon’s office, even joined an ambulance unit.

But she found out that medicine did not fit her temperament. She wanted things done “instantly, without surgery, pills, etcetera”, as she explained in a 1974 interview with the magazine Cinema. Hollywood, she explained, offered real action, since the booming film industry was in need of workers: “(After World War I) it was possible for even inexperienced people to have an opportunity.”

A girlfriend suggested Paramount. Arzner was welcomed and encouraged to check out the different studio departments, and after watching the towering Cecil B. deMille at work, she had her goal set: “If one was going to be in the movie business, one should be a director because he was the one who told everyone else what to do.” That was in the year 1919.

Six months later she was an editor at the Paramount subsidiary Realart Productions, where she edited a total of 52 films. She was so good at the job that in 1922 Paramount commissioned her to edit Blood and Sand, the film featuring the studio’s greatest star, Rudolph Valentino.

She knew this was her chance to break through to directing. She shot some of the bull-fighting scenes, edited the footage, spiced it up by intercutting it with stock footage, and in doing so saved the studio production money. The folks on the upper floors took notice.

One of them was the director James Cruze. He later employed her as – not his right hand, but “his right arm”, as she called it in her Cinema interview. But she wanted more. And she wasn’t shy about asking for it. She made it clear to the Paramount brass that she would leave and join Columbia if she were not allowed to direct.

Walter Wanger, head of Paramount’s New York studio, tried to stall by promising directing jobs sometime in the future. But Dorothy Arzner, now 29 years old, played tough: “Not unless I can be on a set in two weeks with an A picture. I’d rather do a picture for a small company and have my own way than a B picture for Paramount.” Her hard bargain worked: in 1927, she directed her first feature, Fashions for Women.

The film was a commercial success. Paramount green-lighted three more silent films under her direction. And, a year later, entrusted her with the studio’s first talking picture, The Wild Party.

While shooting it, she made an invention that became a piece of film history. Clara Bow, the lead in The Wild Party, was constricted in her movement due to all the newly installed sound equipment around her. Arzner, again, had the “instant” solution: she placed a microphone dangling from a fishing rod above the actress, allowing Bow to move freely. The boom mic was born.

By now Arzner had herself established as a Grade A director. Paramount put a series of features in her hand, such as Charming Sinners, 1929, Sarah and Son, 1930, and Honor Among Lovers, 1931.

Dorothy Arzner always showed herself to be a fiercely independent woman. She never made a secret of her lesbianism and presented herself unconventionally for her time, in suits and short cropped hair. In 1930, she and her live-in partner for forty years, dancer and choreographer Marion Morgan, moved in together and stayed together until Morgan’s death in 1971.

One can assume that it was Arzner’s independence that led her to leave studio employment in 1932 and offer herself as a director for hire. Again, she found great success. She created memorable films that helped along iconic careers: Christopher Strong with Katharine Hepburn in 1933; Craig’s Wife with Rosalind Russell in 1936; and Dance, Girl, Dance with Lucille Ball in 1940. Studios such as United Artists, Columbia, RKO or MGM kept her in demand.

Finally, in 1943, at the age of 47, she turned her back on Hollywood. Why? It is not entirely clear. Sophie Mayer, in her biography “Dorothy Arzner: Queen of Hollywood,” speculates that her retirement might have been a consequence of the infamous Hays Code which fostered sexist attitudes and homophobia.

Arzner did not leave the film world entirely. During World War II she made Women’s Army Corps training films, and years later she joined the UCLA School of Theater, Film and TV, where she supervised advanced cinema classes. One of her students was Francis Ford Coppola.

She was awarded a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, and in 1975, the Directors Guild celebrated her with “A Tribute to Dorothy Arzner.” Highlight of the tribute was a telegram from Katharine Hepburn: “Isn’t it wonderful that you’ve had such a great career, when you had no right to have a career at all?”

Shortly after the tribute, Arzner took her final step of independence: She moved alone to the Californian desert. There, in 1979, she died at age 82.