- Industry

Filmmakers’ Autobiographies: Frank Capra, “The Name Above the Title”

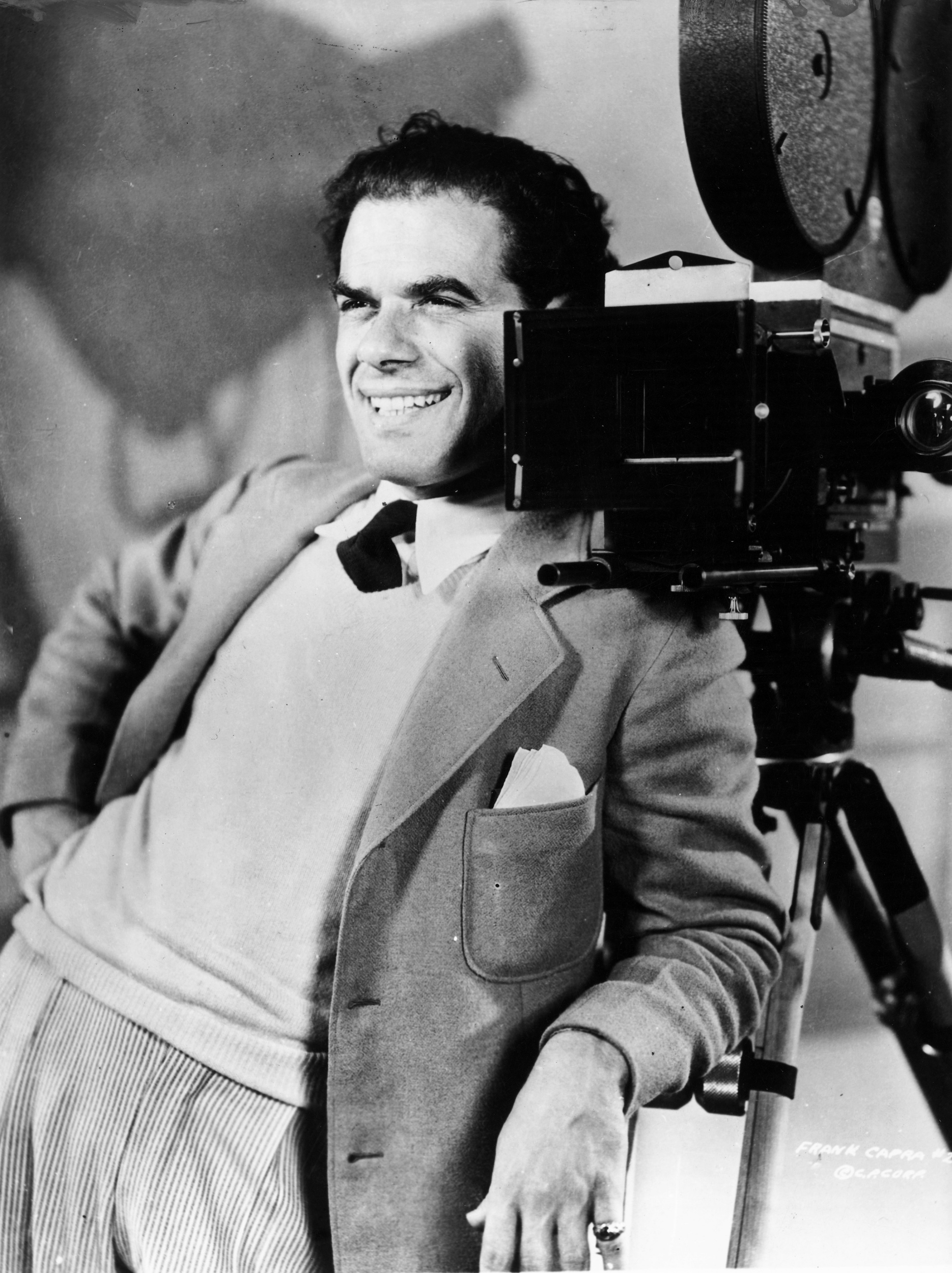

“I have lived a most wonderful life, being given an extremely rare privilege, a forty-five-year ride on the magical carpet of Film!” So writes Frank Capra in “The Name Above the Title”, his voluminous autobiography published in 1971, 20 years before his death at age 94.

In it he reminds the reader that he “helped create the golden era of films,” along Hollywood filmmakers of the thirties and forties, “who thrilled the world with their own works, creative giants in love with their medium, fiercely proud of it, fiercely jealous of it.” Some of their names? Cecil B. deMille, John Ford, George Cukor, Victor Fleming, Leo McCarey, William A. Wellman, King Vidor, William Wyler, and so many more. And reflecting on his past, as one of those surviving giants, he can be legitimately proud of an illustrious career and a legacy of iconic films that sealed his reputation as one of the most influential directors and assured him an enviable place in the pantheon of world cinema. Lady for a Day, Arsenic and Old Lace, It Happened One Night, It’s a Wonderful Life, Meet John Doe, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, You Can’t Take It with You.

In 1961, Capra had directed what would be his last opus, A Pocketful of Miracles, which sadly failed to recapture the magic of his previous works. It was a box-office flop and a stunned Capra could not understand why his faithful audience of several decades had deserted him. Was he suddenly so out of touch? Undeterred, he forged along, trying unsuccessfully for three years to have a studio greenlight Marooned, a pet project about the dramatic rescue of an American astronaut on his way back to earth. It ultimately ended up being made by John Sturges. “So I retired, or more truthfully, I was retired from Hollywood,” Capra sarcastically comments, adding that “there is no greater punishment for a creative spirit than to wake up each morning knowing he is unneeded, unwanted, unnecessary.”

To escape the slow death (his words) of forced retirement, he partly found solace in revisiting the past to write his colorful life story. A quite extraordinary journey that began in 1903 when, at 6 years old, he left his native village near Palermo in Sicily with his illiterate parents and three siblings to go to America. An uncle had suggested the family move there, to the Promised Land. They settled in downtown Los Angeles. It was hard at first to adapt and young Capra resented feeling alienated in the new environment which made him even more determined to find his way out. “I hated being poor,” he remembers, “I hated being a peasant, hated being a scrounging news kid trapped in a sleazy Sicilian ghetto. I wanted out. A quick out.”

At the Speaker of the House’s desk in the House of Representatives on the set of his film, Mr Smith Goes to Washington, 1939; with Gary Cooper and Irving Bacon on the set of Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, 1936; with Claudette Colbert and Clark Gable on the set of It Happened One Night, 1933.

Hulton Archive/Getty Images; Sunset Boulevard/Corbis via Getty Images.

It would take a while before finding the key to his professional future and finally grasp “the fringes of this flying rug, pull myself on it, and ride to adventure, like riding a meteor.”

He tells how he bluffed his way into silent movies in 1922, and despite a total ignorance of moviemaking, directed and produced a profitable one-reeler. Doors opened in Hollywood and he soon got a job as a prop man, then as a film cutter before being hired in 1924 as a gag writer for Hal Roach’s Our Gang comedies. Two years later, he directed his first film, The Strong Man, with Harry Langdon.

He recounts drolly his rise to fame at Columbia Pictures where his brashness and vision had impressed its tyrannical boss, Harry Cohn, “one of the most controversial, damndest, biggest characters Hollywood has ever known.” He directed five cheap films in seven months at the studio. “I attacked films with the ardor of a fanatic.” He had a first solid hit with Submarine in 1928 which got him a three-year contract. Soon he was the star director. Helping the studio to gain financial security and raising its stock value. Rival moguls like Louis B. Mayer at M.G.M. tried to borrow him.

The chapter on the making of It Happened One Night in 1934, is full of amusing tidbits on Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert. And how the actress, Capra recalls, “fretted, pouted, constantly argued about her part, challenged my slap-happy way of shooting scenes, how, in the famous hitch-hiking sequence, she refused at first to pull up her skirt and show her leg.” When a chorus girl was hired as her body double, she relented and agreed to do it. An immense success, the film was the first ever to win all five major Academy Awards statuettes.

“To me, films were novels filled with living people,” Capra opines. “I cast actors that I believed could be those living people. Gary Cooper was Longfellow Deeds, James Stewart was Jefferson Smith and George Bailey.” Same for Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn who starred in State of the Union. There are many anecdotes on Bing Crosby (“not an easy man to know, but a class act and very witty”), Glenn Ford, Bette Davis, Harry Langdon, Gary Cooper (“innate integrity”), Walter Huston, Barbara Stanwyck, Frank Sinatra. At the top of their talent, under his direction, those stars helped him convey idealistically “the cause of the gentle, the poor, the downtrodden.”

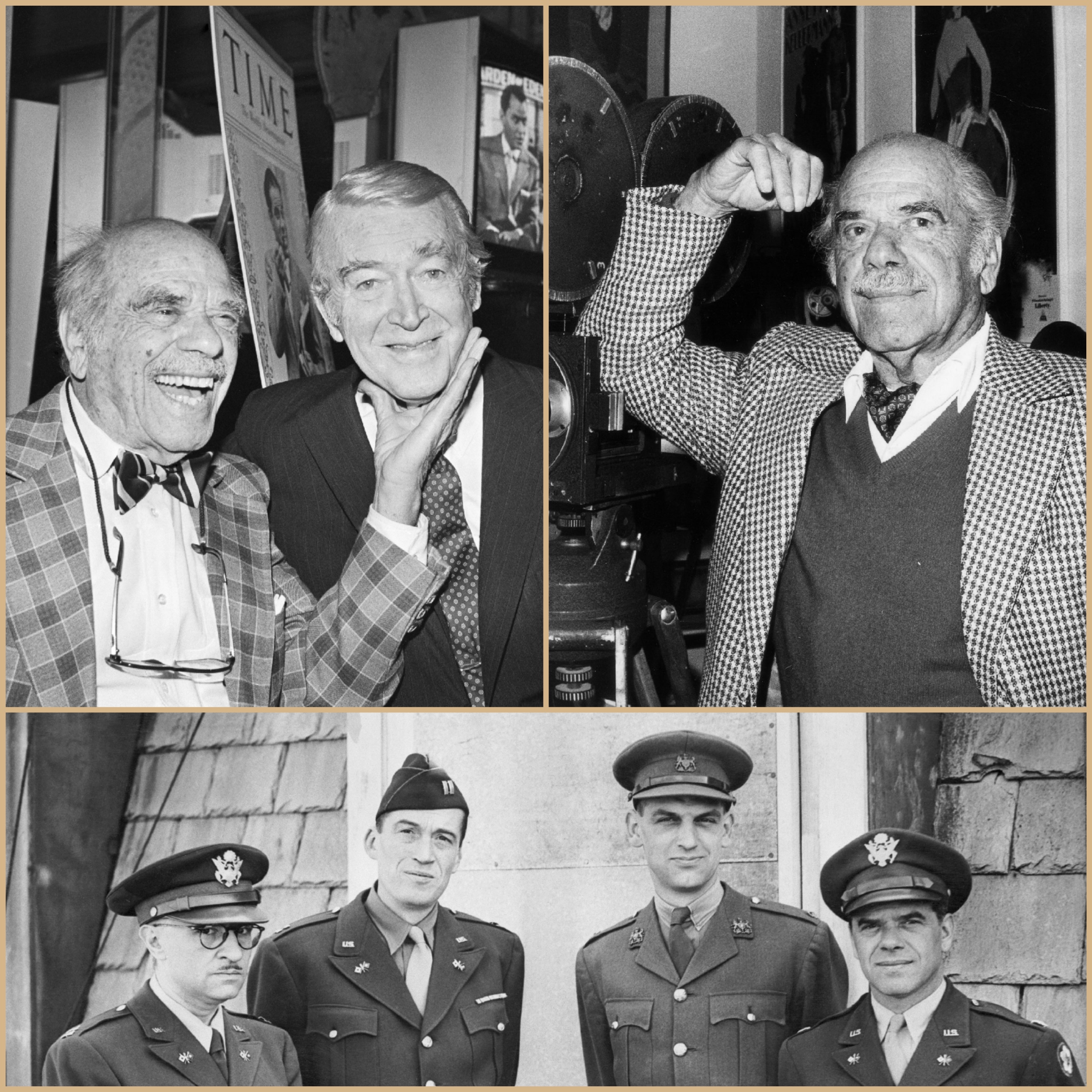

With James Stewart at a luncheon at the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Science, 1985; during a visit to the Museum of Cinema in Milan, Italy, 1977; the then-Colonel Frank Capra, with Captain John Huston and scriptwriter Captain A. Veiller with (center) Major Hugh Stewart, Officer commanding the British Army Film Unit – the filmmakers had recently arrived in London from the U.S. War Department in Washington, D.C., to confer on future release of educational and combat feature films by the Army Film Department, 1944.

getty images/ mondadori via getty images/

In Hollywood, the dream factory of “make-believe’s sound and fury,” he witnessed firsthand “impermanence, change, instant stardom, instant limbo.” But his passion never diminished, as he pursued his quest to always improve his style and innovate. “Film is a disease,” he states. “When it infects your bloodstream, it takes over as the Number One hormone, it bosses the enzyme, direct your pineal glands, plays Iago with your psyche. As with heroin, the antidote for film is more film.” On April 8, 1946, after a four-year break from feature filmmaking because of the war, he began shooting It’s a Wonderful Life. “All that I was and all that I knew went into its making at a pace that was a four-month non-stop orgasm.” But he alludes also to a deep “sense of loneliness in making it, that was laced with the fear of failure.” And reminds the reader it was not that well-received at the release but that it became a beloved cult favorite over the years.

Prone to quick-witted colloquialisms, Capra never shies away from describing his various states of mind, raw emotions always on his sleeve, impulsive and impatient. There are no holds-barred confessions about his dealings, disappointments, and gratifications with the various studio heads and stars he had to deal with through the years. He proudly enumerates his number of Oscars. And the ones he should have won. He alludes to periods of disillusion, well aware that “filmmaking is not a profession in which one can mellow gracefully. It is a hot-eyed, hot-juiced, high-staked game of unrecallable hunches and gut decisions no computer can make for you. In Hollywood one moves fast, thinks fast and fades fast, those who think logically fading the fastest.”

When he wrote these memoirs, at the beginning of the seventies, the emergence of a new wave of filmmakers made him optimistic about the future of cinema with “the dawning, and a promise of greater giants.” Impressed by films such as 2001 A Space Odyssey, Patton, Airport, Love Story, Ryan’s Daughter.” But “who is to speak for the American film?” he wonders. “Sidney Lumet, Arthur Penn, Mike Nichols, Norman Jewison, Martin Ritt, Arthur Hiller? Perhaps. But not by degrading the values of love and glorifying its dementia.” He thinks that “Stanley Kubrick is trying his best to say something but that he will- when he learns to say it simply.” He rambles a bit about the disappearance of “the power of morality, of courage, of beauty, of the great love story.” An understandable statement from someone for whom such qualities in human beings were paramount in his storytelling. In his foreword to the book, John Ford lyrically wrote that “a great man and a great American, Frank Capra is an inspiration to those who believe in the American dream.”

One could not sum up better what he still represents to this day.