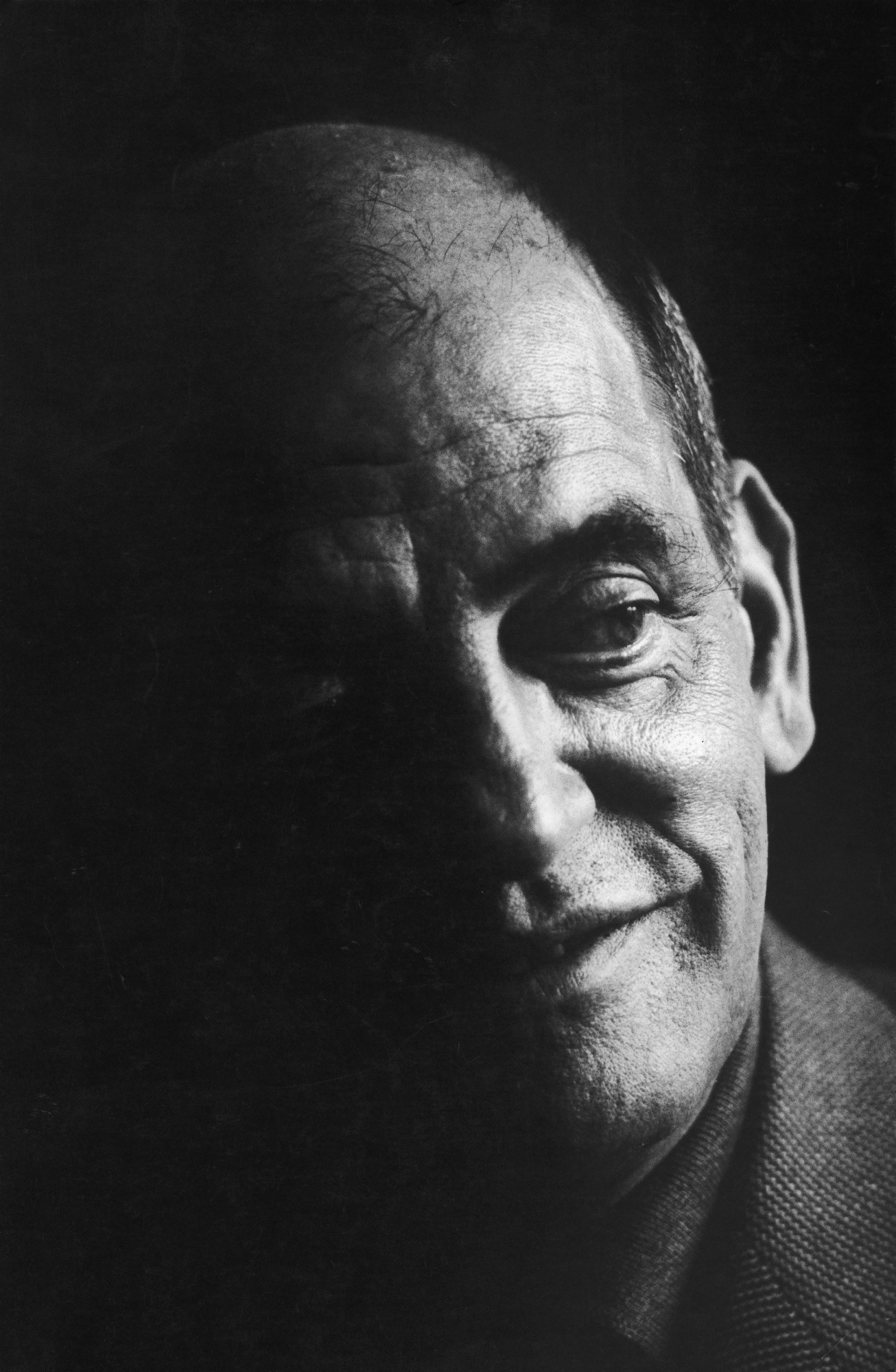

- Film

Filmmakers’ Autobiographies: Luis Buñuel, ‘My Last Sigh’

“In this semi-autobiography, where I often wander from the subject like the wayfarer in a picaresque novel seduced by the charm of the unexpected intrusion, the unforeseen story, certain false memories have undoubtedly remained, despite my vigilance. But it doesn’t matter. I am the sum of my errors and doubts as well as my certainties. Since I am not a historian, I don’t have my notes or encyclopedia, yet the portrait I’ve drawn is wholly mine, with my affirmations, my hesitations, my repetitions and lapses, my truths and my lies. Such is my memory”. So warns Luis Buñuel at the beginning of ‘My Last Sigh’ published in February 1983, six months before his death at age 83 in a Mexico City hospital.

Therefore, don’t expect a straightforward approach from the man considered the father of surrealist cinema, a delineator of freighted catholic erotica, master of visual double entendre. No wonder François Truffaut called My Last Sigh “the nonconformist autobiography of a great filmmaker – moralistic, modest and extremely witty.” Along with the pages, the elderly Buñuel, reflecting on his long life, invites the readers down memory lane with distanced nostalgia sharing with them many amusing but also melancholic anecdotes.

Starting with his very austere upbringing in Calanda, a large village of the northern Spanish province of Aragon, he recalls growing up in a quasi-medieval environment but rich “in forbidden delights and the thrill of the first sexual stirrings”, adding that “the two essential feelings of my childhood that lingered on through adolescence were a deep sense of eroticism heightened by the overpowering presence of religion mixed with the constant awareness of death” A potent cocktail that would later fuel the themes he explored in many of his most provocative films: Viridiana, The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, The Exterminating Angel, The Milky Way, The Diary of a Chambermaid, Phantom of Liberty.

In 1963, shooting Diary of a Chambermaid with Jeanne Moreau.

jean-claude sauer/paris match/ getty images

At 17, moving to Madrid to study meant freedom and the discovery of literary life at the famous Café Gijon, the complicated friendships with Federico Garcia Lorca and Salvador Dali. 1925 found him in Paris, intending to become a journalist. There he met the members of the Surrealist movement which had such an impact: Max Ernst, André Breton, Paul Eluard and others. He remembers his mother “weeping with despair” when, in 1928, he told her he wanted to make a film. She would nonetheless help finance Un Chien Andalou, which he directed, from a script co-written with Dali, based on some of their dreams. It would become an instant sensation at the release a year later with one of the most memorable images ever put on screen, that traumatizing shot of the razor blade slicing open a woman’s eye…Sealing his status as an iconoclast and avant-garde surrealist filmmaker.

Hollywood soon came calling and Buñuel settled in Tinseltown in late 1930, under contract to MGM. He ended up not working but, for the better part of a few months, enjoyed his time with the film community. He would be back twice more. But unlike many other European filmmakers, he never wanted to become a Hollywood director. “My films would have been very different, and should you ask which films, I’d again have to say I don’t know and since I never made them. So, I don’t have any regret.”

As for his personal tastes in movies, they are eclectic. He praised Kubrick’s Paths of Glory, John Huston’s The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, Fellini’s Nights of Cabiria, La Strada, La Dolce Vita, Roma, but admits walking out of Casanova before the end. Other favorites are Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin, René Clément’s Forbidden Games, Marco Ferreri’s La Grande Bouffe which he sums up as “a tragedy of the flesh and a monument to hedonism.” He adores Fritz Lang’s early films, Jean Renoir’s prewar ones, Buster Keaton, The Marx Brothers, and De Sica, but detests Rossellini’s Rome, Open City and From Here to Eternity. Of his owns, he claims that he never watched any of them once they were made.

With Stephane Audran on the set of The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, 1972.

greenwich films/sunset boulevard/corbis/getty images

Sadly, he doesn’t say anything about Catherine Deneuve even though he directed her in two of his most famous films, Belle de Jour and Tristana.

During the Spanish Civil War (1936-39), he sides with the Republicans. Based in Paris for a while in charge of overseeing propaganda on their behalf, he managed to issue safe-conduct passes to Hemingway, Joris Ivens, and John Dos Passos so they could go to Spain and work on their documentary. He recalls his thirty years living in Mexico where he had settled in 1946. One of the films he shot there was Death in the Garden with Simone Signoret whose behavior he describes as “at best unruly and at worse very destructive to the rest of the cast.”

His return to Europe in 1960 marks the beginning of another very fertile period, ending in 1977, with his last film That Obscure Object of Desire. He mentions a list of projects he was never able to make, like Lord of the Flies. Same with Johnny Got His Gun after working on the script with Dalton Trumbo. None of the eight versions of an adaptation of Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano could ever convince him to direct the movie. Because of scheduling conflicts, he had to say no to Woody Allen who offered him $ 30,000 for two days’ work to play himself in Annie Hall. Marshall McLuhan replaced him in the famous scene where Annie and Alvy Singer are in line for The Sorrow and the Pity.

Directing Catherine Deneuve on the set of Belle de Jour, 1967.

reporters associés/gamma-rapho/getty images

After years of crippling ailments, which he lists extensively, “painfully conscious of his decrepitude”, he confesses that “the thought of death has been familiar to me for a long time.” But its ineluctability doesn’t scare him. His daily life is set up in a routine. “I wait, I think, I remember, constantly looking at my watch.” Finding comfort each noon in “the sacred moment of the aperitif.” Scotch never did anything for him but he brags about his Martini-making expertise and offers advice for the perfect one. “Simply allow a ray of sunlight to shine through a bottle of Noilly Prat before it hits the bottle of gin.”

As he drifts towards his last sigh, he can’t help but imagine one final joke. “I convoke around my death bed my friends who are confirmed atheists as I am. Then a priest arrives and to their horror, I make my confession, ask absolution for my sins and receive extreme unction. After which I turn over and expire.” Incorrigible provocateur until the very end.