- Film

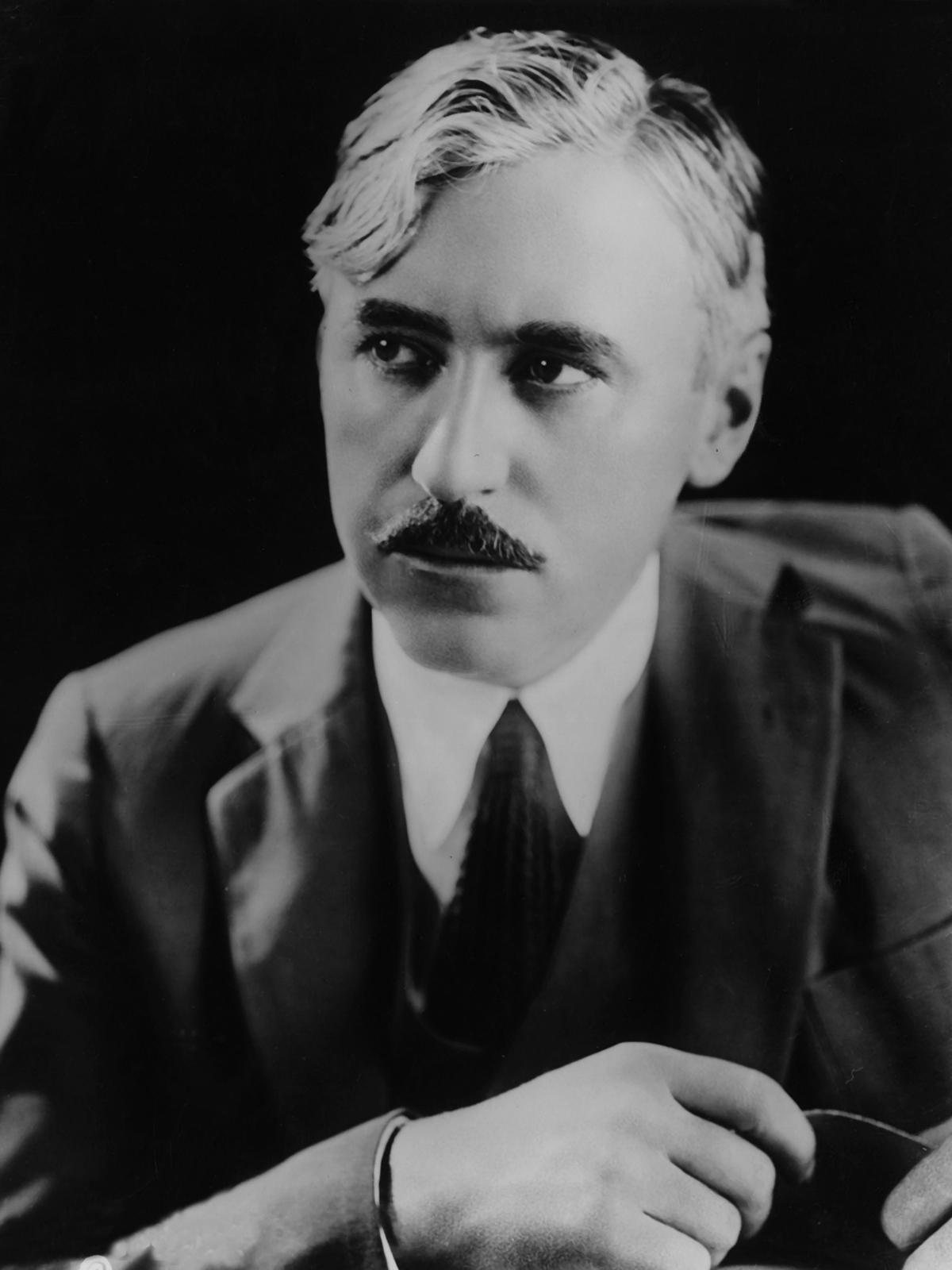

Filmmakers’ Autobiographies: Mack Sennett – King of Comedy

The Garden Court Apartments, at 7021 Hollywood Boulevard, are long gone, replaced by an ugly mini-mall with a drugstore, a fitness club, and a Fresh and Easy supermarket. Mack Sennett used to live there, just opposite the still standing Roosevelt Hotel when it was a fancy address. This is where he worked on his autobiography, so appropriately titled “King of Comedy”, published in 1954, six years before his death at 80.

“As I look back on more than half a century of professional nonsense, my life unwinds like a two-reel comedy chase sequence – a leaping funnyman flees from the Keystone Cops, falls off a cliff into a bevy of Bathing Beauties, suddenly discovers a custard pie in his hand”, he writes at the beginning of his memoirs. In one sentence, he sums up the cocktail of ingredients that became his trademark of slapstick in hundreds of short films that delighted audiences in the silent movie era. “Many people, some of them astute, allow that I was the originator of motion picture comedy,” he muses. “That may be stretching things a bit, but I like the idea and my denials are weak.”

He describes himself as “a Canadian farm boy with no education” who moved from his native Quebec to Connecticut with his family when he was seventeen, finding work initially as a boilermaker. But he really wanted to become an opera singer so, at twenty, he ventured to New York, where he only managed to get odd jobs in burlesque theaters, occasional engagements as a chorus boy, and bit parts on Broadway shows. By 1907, nickelodeons were springing up everywhere, an increasingly popular attraction. “I had heard that there was money in motion pictures,” he writes.

On a whim, he applied for a job at the Biograph Company near Union Square. On his birthday (January 17, 1909), he was hired. It was a turning point for Sennett who soon started to act and direct under the tutelage of D.W. Griffith. “He was my day school, my adult education program, my university.” He would listen to Griffith as he detailed “the great theories which made him the absolute pioneer of the screen. He saw stories as mass movement suddenly pinpointed and dramatized in human tragedy. What I saw in his great ideas was a new way to show people being funny.” Sennett was never able to convince Griffith that cops could make for good comedy material.

He remembers wistfully, “the most important thing in my life was a girl, a seventeen-year-old brunette, barely five feet tall with a blazing ambition to become an actress.” Her name was Mabel Normand and she had just joined Biograph too. He instantly fell for her and made her a promise: “When I get my own company, I will make funny pictures and put you in them.” And he did. He convinced her to move to California with him in January 1912 at his newly formed Keystone Studios, based in Edendale, now Echo Park, where he had settled on a vacant lot that would quickly extend to twenty-eight acres.

Sennett produced one hundred forty films in the first year of activity. “We made funny pictures as fast as we could for money,” he recalls. “We knew we were experimenting with something new. Our specialty was exasperated dignity and the discombobulation of authority and we had fun doing it.”

Soon the studio became a training ground for a new breed of innovators in the comedy genre. For Sennett, “they were artists, and great ones, roaring extroverts devoted to turmoil who competed with each other in murderous antics in front of the camera and got themselves so wound up that they seldom knew when to stop gyrating.”

The Keystone lot was their playground. When Charlie Chaplin first came in, no one was really impressed. Mabel Normand refused to act with him. But she quickly changed her mind. Their pairing proved infallible chemistry. “I can’t claim I had the foresight to see Chaplin’s future,” he admits. All changed when he came up with the tramp persona and its iconic costume.

“I am honestly proud of the many unknown talents I discovered and brought to the screen,” he said. “Roscoe ‘Fatty’ Arbuckle, Gloria Swanson, Buster Keaton, Carole Lombard, Bing Crosby, W.C. Fields, Harry Langdon, and a good many others. Not to forget, the Keystone Cops, the Mack Sennett Bathing Beauties, and the only pastry that became an international star.”

On the latter topic, he writes at length about the methodical timing that went on to perfect the pie-in-the-face throwing technique. He credits Normand for being the first to hurl one at Ben Turpin in 1913. “It became, in time, a learned routine, like a pratfall, the double-take, the slow burn and the frantic leap, all stock equipment of competent comedians.” He describes the 108: “A comic fall which only the most skillful athletes can perform without lethal results. One foot goes forward, the other foot goes backward, the comedian does a counter somersault and lands flat on his back.”

He explains his concept for the creation of “The Bathing Beauties” and mentions some of the actors he failed to hire like Harold Lloyd. He has no ill feelings towards the many who left him for rival studios and juicier contracts as soon they became famous under the Keystone banner – Buster Keaton for one. “We could have done improbable things together,” he muses. “But the Great Stone Face was cut out for larger works than we had to offer. He was one of the first to set the pattern that kept me in trouble for the rest of my life: start with Sennett and get rich somewhere else!”

But the recurrent leitmotif of his autobiography has to do with Mabel Normand. “My happiest and saddest memory,” he movingly writes. “She was the most gifted comedienne Hollywood ever knew.” With him, she became one of the very first silent screen stars. She also broke his heart. They were engaged and unengaged more than twenty times. He put up with her increasing eccentricities, her unpredictability, her wild spending sprees, her erratic behavior, her piles of contradictions, but never was he able to figure her out.

He writes at length about the scandal that almost torpedoed her career. The mysterious unsolved murder of the director William Desmond Taylor on February 1, 1922. Normand had visited him that evening. After one last film together released that year, she started her own company, wanting to go more into dramatic roles. In 1926, she was signed by Hal Roach. She died four years later. “I never married,” Sennett simply concludes. “There was only one girl.” He religiously kept scrapbooks containing forty-eight thousand clippings about her.

“The Twenties marked a high-water point for me,” he concludes. “We made big pictures, made big money, and thought it would last forever.” It did not. A deal with his friend Adolph Zukor at Paramount proved an ill-fated decision. As a repercussion of the Wall Street crash of 1929, the studio went into bankruptcy. “And I went with it,” he says matter-of-factly. “I lost the studio, the mountain, the acres of lands in Los Angeles, the whole shebang once upon a time valued at fifteen million dollars, (a staggering $285 million in today’s money). I was wiped out.”

By 1935, he had given up moviemaking and retired. Three years later, he was bestowed an honorary Oscar. “It was handed to me by the man who started with me many years ago as a youngster in the gag room and scenario department: Frank Capra.”

Despite the many anecdotes told with candor and deadpan humor, the witty remarks, Sennett cannot hide underlying melancholia. “Now, as I think it all over, I wonder if I have told the truth and if any man does, or can when he pretends to write his life story. I wanted to talk about the comedies and how we made them, and about the funny fellows and pretty girls who acted in them. They are a lost breed. Their like may never walk, tumble or pratfall again.” But for many fans and cinephiles, they still do, more than a century after they first appeared on the silver screen, at the dawn of Hollywood.