- Industry

Filmmakers’ Autobiographies: Marcel Carné, “La vie à belles dents”

Any cinephile and true movie fan can name at least one film made by French master of poetic realism Marcel Carné, most probably his 1945 masterpiece Children of Paradise. Other memorable ones include Drôle de drame (Bizarre, Bizarre), Daybreak, Port of Shadows, Hôtel du Nord, The Devil’s Envoys.

In 1975, the 69 year old Carné published his autobiography “La vie à belles dents”, a title that can loosely be translated as “Living life to the fullest”, or “Taking a joyful bite at life.”

A year before, he had just released what would be his last feature, The Wonderful Visit, to mediocre reviews and tepid box-office. He could not find financing for his next projects which, one after the other, could not materialize or were turned down. He felt less and less welcome in the business and could only assume why. “I won’t deny it,” he admits candidly, “after the war, I directed some movies that, in spirit and in scope, were not worth the ones I had made until 1946.”

His memoir, he insists, was never meant to settle any score, even if it often feels that way as he goes into great detail about his numerous complaints and hardships. “I wanted to show that filmmaking is a non-stop struggle, an uphill battle of all hours, all instants. Against everyone: producers, distributors, theater owners, and also at times, the actors and technicians you have chosen in good faith. It is a long and arduous journey, trying to avoid the shifting sands along the way, at the end of which victory, success or a winning prize are rarely guaranteed. But no matter what, you must start again, knowing you will be faced with the same hurdles: incomprehension, stinginess, hostility often, distrust always.”

Growing up in Paris where he was born in 1906, Marcel Carné never imagined himself having a film career. As a teenager, he was endlessly fascinated by the music-hall and “its perpetual creativity”, by extravagantly produced shows at Les Folies Bergère and Le Palace, where he saw Mistinguett, Maurice Chevalier and the Dolly Sisters, in all their glory. Every day, he would sneak in theaters (he had no pocket money) to watch the latest silent works of Chaplin, Murnau and Fritz Lang. He had no intention of becoming a cabinetmaker like his father. “I started to see clearer in me and perceived what my future could be,” he writes. “The ecstasy of discovering that new Art that was cinema. I had an epiphany. My life would be in the cinema. That was my calling. This will surprise you, but I did not think of directing at the time.”

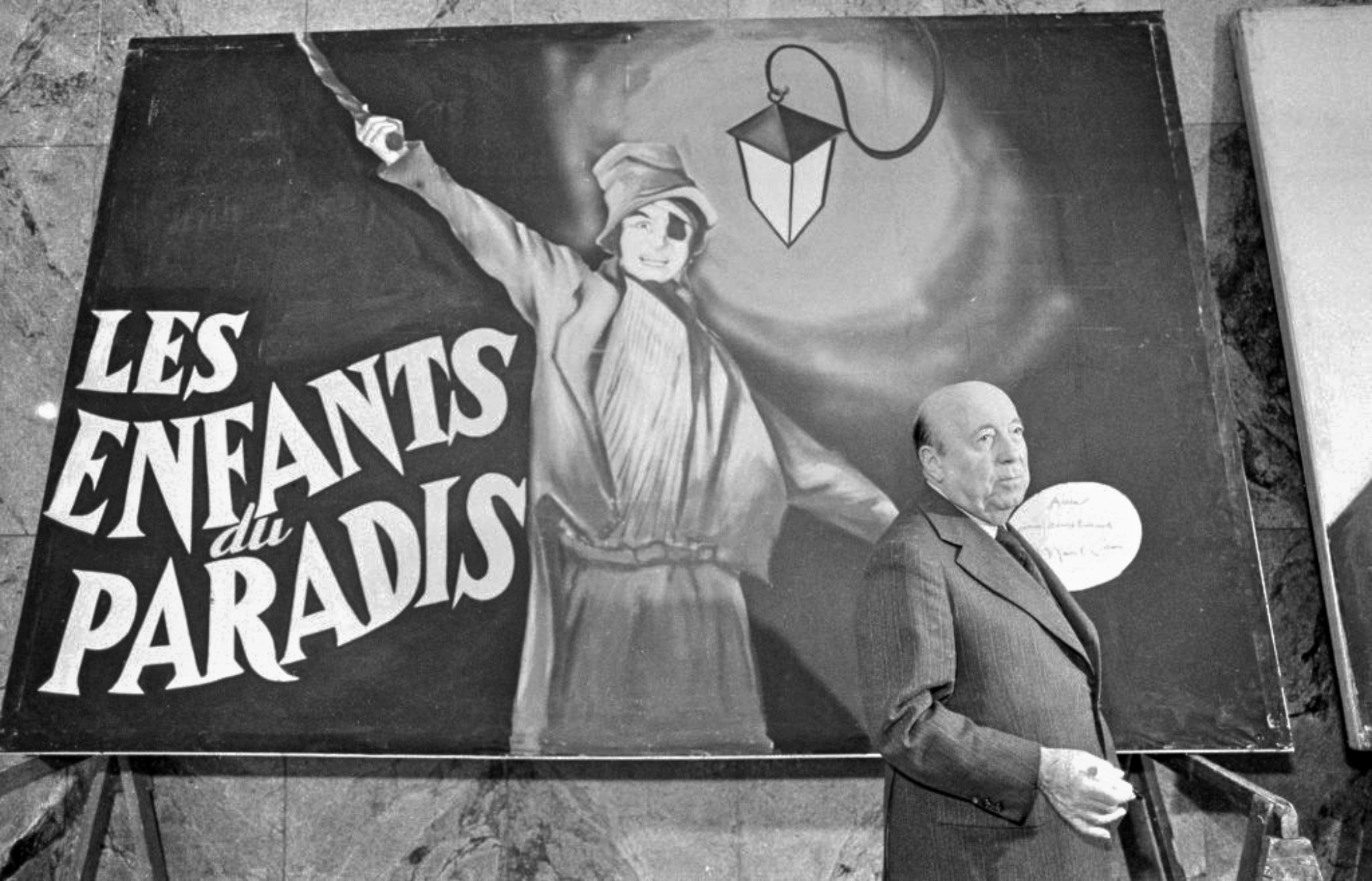

Top: On the set of Les Enfants du ParadisHôtel du Nord, directing Arletty; and with Jean Gabin on the set of L’Air de Paris, 1954.

Pathé/Roger Forster/Sunset Boulevard/Corbis via Getty Images/S.E.D.I.F./Sunset Boulevard/Corbis via Getty Images/oger Viollet Collection/Getty Images

In 1929, he bought himself a camera and some film stock and shot Nogent, Eldorado du Dimanche, a semi-impressionist silent short documentary that he edited in his bedroom. “I did it to see if I could do something.” Around that time, at a dinner party, he met the imposing actress Françoise Rosay, wife of Jacques Feyder, one of the leading filmmakers who soon hired him as his assistant. He worked on several of his films , the last one being the costume romantic drama Carnival of Flanders, in 1935. The following year, he felt ready to direct his first movie Jenny. It would be his first time teaming up with playwright and poet Jacques Prévert who wrote the screenplay. “I had a ten-year long wonderful collaboration with him. We completed each other and got along famously.” Prévert concocting many memorable lines for actors like Arletty (her immortal “Atmosphère, atmosphère. Est-ce que j’ai une gueule d’atmosphère?” or « Paris is very small for those who love each other with such great love”), Louis Jouvet, (« Bizarre. Moi, j’ai dit bizarre. Comme c’est bizarre. »), Jean Gabin and Michèle Morgan, Jules Berry, Michel Simon. Together they infused pre-war French cinema with poetic realism, though Carné preferred to call it “le fantastique social.” Another major contribution to his films was Alexandre Trauner, the Hungarian-born production designer responsible for some of the most spectacular sets ever put on screen.

During the war in occupied France, and despite numerous restrictions, Carné managed to direct his two chefs d’œuvre: Les Visiteurs du soir and Les Enfants du Paradis. He was criticized for them and he had to justify his choices repeatedly over the years. In 1946, he wanted Jean Gabin and Marlene Dietrich to star together for the first time in Les portes de la nuit (Gates of Night), capitalizing on their well-publicized love story. When the couple opted out, he resorted to choosing Yves Montand, then know as a singer, at the urging of Edith Piaf. In the film he hummed Les feuilles mortes, with lyrics by Prévert, that Nat King Cole would later interpret as Autumn Leaves. Montand was far from grateful of the result. Because of the film’s poor box-office, he accused the director of having stalled his burgeoning career for the next 20 years.

In 1958, Carné had his last commercial success with The Young Sinners (Les tricheurs) in which he cast an unknown Jean-Paul Belmondo, a year before Breathless made him a star. The New Wave tsunami was then shaking the French cinema, forever changing its landscape. Directors like Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut and Claude Chabrol, were highly critical of their predecessors. Something Carné deeply resented. “It is very simple,” he firmly believes, “we experienced a period in which a new director was born every morning. (…) Once emerged from their autobiographical stammering, the others could only demonstrate their incapacity to build a story.” His attempt to follow in their vein, with the 1960 Wasteland, was a failure which did not resonate with the young audiences it was obviously intended for. He claimed that “the New wave assassinated me, but then, it killed the cinema too.” A provocative, if a bit unfair, statement, but understandable from Carné’s point of view.

In 1965, he went to New York to film entirely on location the adaptation of George Simenon’s Three Bedrooms in Manhattan, with Annie Girardot and Claude Giraud. He wanted to prove he was “not a man of the past, unable to work anywhere other than in the controlled environment of a studio, on a soundstage with the comfort of elaborate sets and lightning.” Once again, French critics were not kind, and even more virulent with his next feature, Law Breakers with Jacques Brel, released in 1971 to total indifference but well received at the Venice Film Festival.

“Why I am always honored and celebrated abroad,” he wonders, “while in the country that is my own, in which I was born, I encountered only attacks, sarcasm, and even disdain from those who claim to love Art in which I have devoted all my life?”

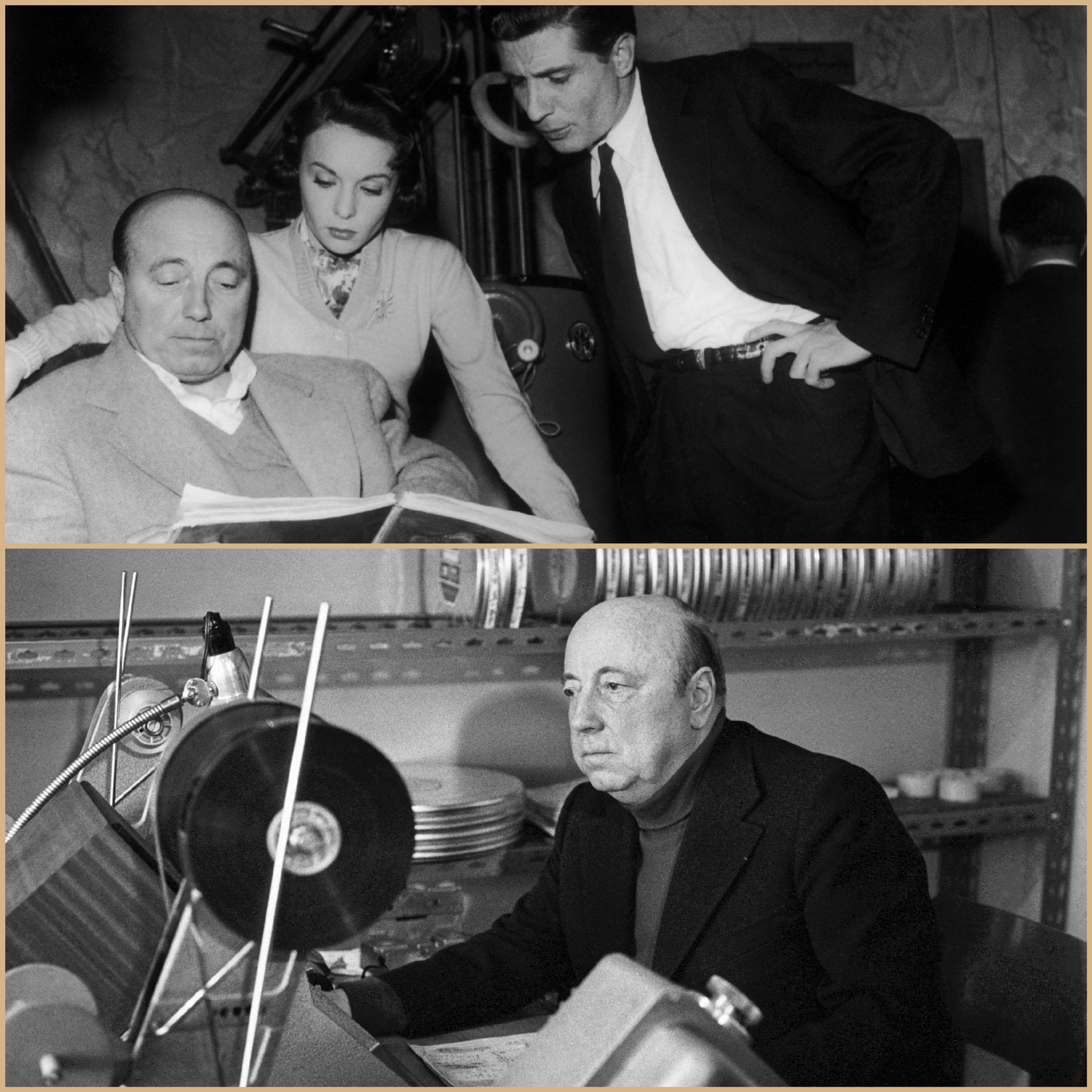

(top) With Françoise Arnould and Gilbert Becaud at Francoeur studio in Paris, on the set of The Country I Come From, 1956 – the cast is due to a fall after tripping on a cable; (bottom) in the cutting room.

Keystone-France/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images/Roger PicardINA via Getty Images

In the book he elaborates at length on many aborted projects. Germinal, Mary Poppins, a biopic of Diaghilev with Orson Welles in the title role and Rudolph Nureyev as Nijinski, a modern remake of Camille with Jeanne Moreau. Another one in the early seventies with Alain Delon who, when contacted, had his powerful agent tell Carné that “Monsieur Delon only works with directors of his generation.” A blatant lie, as he sarcastically remarks, since the actor had made films with Luchino Visconti and Julien Duvivier, both at least 30 years older than he was at the time!

“Maybe,”, he finally ponders, “due to my simplistic philosophy, I have been able to endure adversity with serenity, to never become embittered in face of repeated hatred and malevolence.”

Looking back at his career, he curiously opines that “none of my films have satisfied me entirely.”

In concluding his autobiography, he mentions that the anagram of his last name can be spelled écran. Translated, the word means screen.

How appropriate.