- Film

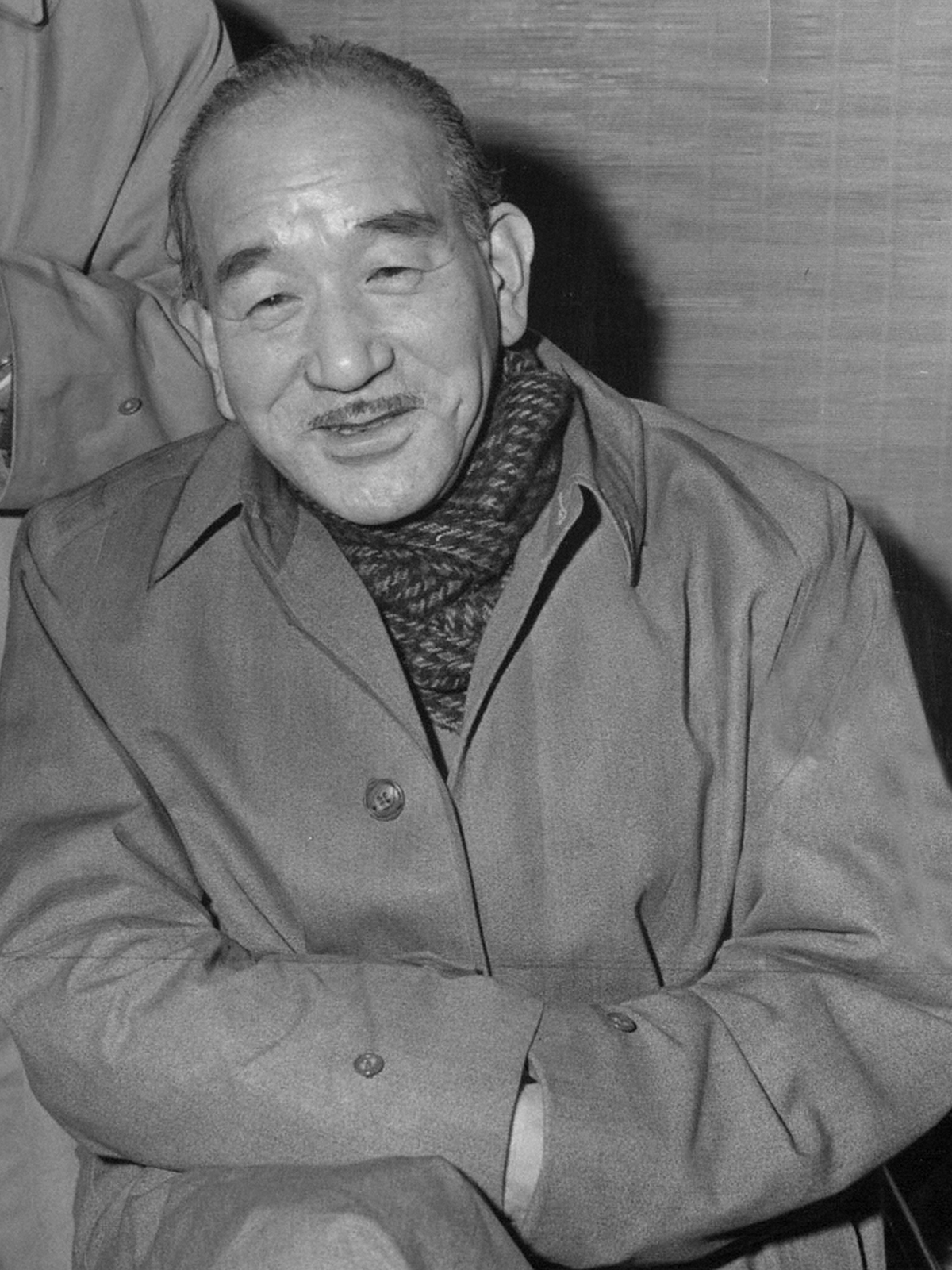

Filmmakers’ Autobiographies: The Ozu Diaries

Tokyo Story, Good Morning, Early Spring, Floating Weeds, Late Autumn, Equinox Flower, The Flavor of Green Tea over Rice are just a few of the most movingly memorable films directed by Yasujirō Ozu.

Besides a legacy of many unsurpassed masterpieces, the prolific filmmaker also left 32 pocket agendas in which he diligently recorded facts and events of his daily life, from 1933 until a few months before his death in December 1963, at age sixty. Initially compiled and published in Japan in 1993, their content was recently reissued in a French edition in the form of a hefty collectors’ volume.

In 1,260 pages (yes, 1,260) the curious cinephile and Ozu fan will get the thrilling feeling of gaining access to an inner sanctum, of being in the director’s shadow. Rather than a proper diary, this is a journal that provides a firsthand testimony written in Haiku style paragraphs and mostly telegraphic sentences. Like the seismograph of a life detailed in its most trivial way, the very essence of life itself, reduced to its most factual expression, transcribed in a succession of fleeting impressions, ephemerous snapshots, elusive sensations in the shibui vein, that Japanese aesthetic of organic minimalism and deliberate restraint, so authentically reflected here, with no effusiveness.

So, don’t expect Ozu to confide his love life or share acrimonious gossip. If he often mentions his family members, his dealings with Shochiku, the studio he worked for, and the names of his collaborators, he barely evokes his working methods, never says what he thinks of his actors, even about his many regulars, Chishu Ryu (who appeared in almost all his films), Setsuko Hara, Haruko Sugimura or Shin Saburi.

There are no journals from the forties which he spent partly in Singapore, where he was imprisoned in 1945. The flow resumes in 1951, a period in which he signed many of his most acclaimed and successful works. Paradoxically, during this artistically rich and fulfilling period, his entries become more and more succinct. He has a quite active social life, a sort of frenetic conviviality in contrast with the Jansenism of his moviemaking and the highly stylized and calibrated mise en scene, shot at his trademark tatami level.

A keen cinema-goer, Ozu watches his colleagues’ works: those of Mikio Naruse (he was impressed by Floating Clouds, “really a great film.”), Kenji Mizoguchi, and also many American and French releases. He enumerates them without offering his opinion, just like he notes the results of Sumo championships which he increasingly followed over the years, listing the teams’ victories and losses, with detached scrupulousness.

Clearly an alcoholic (his sake consumption is impressive, often starting in the morning at breakfast), he painstakingly details his many hangovers, the various levels of inebriation, and drunken intoxication with a matter-of-fact distance that is often achingly poignant.

There are countless references to the weather as he obsessively gives every day reports on sunshine, clouds, rain, snow, wind and temperatures.

An incurable insomniac, he needs to often take naps, several hours a day, and never misses his bath rituals. Food is a big part of these pages. Ozu has specific tastes and religiously reports on what he ate, his gourmandise in full display, whether at home or when going out. Comforting ochazuke (green tea over rice), tonkatsu (deep-fried pork cutlet), broiled Sanma fish (Pacific saury), a delicacy eaten in Autumn, grated Iguame, kamonabe (sliced duck dipped in sake and soy sauce broth) … He is a regular at restaurants like Wakamatsu, Mitzutaki, Hôraiya, Nakamuraya and Tôkôen … His favorite sweets, namagashi, and assorted mochis come from the three-hundred-year-old Nagato shop in the Nihonbashi area.

He mentions the many bars he patronizes. A litany of evocative names, like forgotten beacons in the Ginza nightlife. L’Espoir, (where his longtime friend Kayoko works as a hostess), L’Ami, Lupin, L’Eskimo, Lindô . Maybe, in some of them still in activity, his spirit lingers on. He buys books, agendas, calligraphy papers and pens at Itoya, Kinokuniya and Maruzen and shops at the high-end department stores Takashimaya and Mitsukoshi. All purchases are dutifully itemized.

When thinking of Ozu’s cinema, its low-camera angles instantly come to mind, with the flawless cutaway shots, like still-lifes, silent contemplations of the city in motion, of isolated landscapes, of laundry drying in the wind, of infinite skies, endless railroad tracks and the soothing rumble of trains. There are stories of women searching for emancipation, of harsh but endearing fathers, of daughters not wanting to get married, of changing lifestyles, generation conflicts, of urban metamorphosis, of the passing of time, of people who leave, those who return, and those who have stayed. Ozu’s films are a mix of it all, with similar titles, similar characters, familiar places and faces, and recurrent themes. In the end, those Journals are an entry door in this relentlessly routine universe, banal in the most beautiful and elegiac sense of the term. To read these thousand pages, or watch his films again in chronological order, is to confront the redundancy of life, with the bittersweet impression that everything repeats itself without really evolving, even though there are inconspicuous and subtle mutations drowned amongst the numbers of days and years. And, after a while, the weight of time gets to you like a vertiginous and intoxicating sensation.

So, to better illustrate Ozu’s poetic melancholy and self-deprecating humor, here is a random and arbitrary selection of his entries.

Monday, February 20th, 1933.

“Went to buy Dial sleeping pills. Come to think of it, my ambition is to become a good craftsman.”

Sunday, April 23, 1933.

“Discussion with Kogo Noda [his screenwriter partner since 1927] about cinema technique. Namely: eliminate too sophisticated shots. If possible, use temporal ellipse. And finally, remain at my place, which, as a director, means being close to the camera. On that issue, I still have a lot of progress to make!”

Monday, August 7, 1933.

“The camera’s range is only a small window to the world. Love is only a small window on life. You have to think twice before pressing the shutter button.”

Tuesday, May 8th, 1934.

“Day: editing. [of A Mother should be Loved]

Night: editing.

Five empty bottles of sake.”

Drafted in the Army in 1937, Ozu is sent to Central China where he will spend two years.

Friday, January 13, 1938.

“Opening today of an “entertainment center”. Our unit gets to inaugurate it. We are given two tickets, condoms and lubricant cream. They are fifteen life-size dolls. Three Korean and twelve Chinese. Price is 1.5 Yen for a half hour and two for one hour.”

Wednesday, January 24, 1951.

“I read The Idiot screenplay written for Kurosawa: incomprehensible! That the character be an idiot, why not, but do the screenwriter and director also need to be?!”

Thursday, March 19, 1953.

“Another day without toiling on the script [of Tokyo Story] Every occasion is good to avoid working, namely all the cups of sake poured by Noda which induced me to a gentle sleep under the kotatsu [traditional low table covered with a heavy blanket with a charcoal brazier for warmth underneath] …”

Monday, June 1st, 1953.

“With the month of June, also come the sorrows and melancholy.”

Friday, May 8th, 1953.

“Sake and grilled salted Suzuki [seabass] for dinner. It is the season and really delicious.”

Saturday, January 1st, 1955.

“Stop drinking in the morning. Stay attentive to the things in the world.”

Friday, June 24th, 1955.

“We worked in the morning and completed the screenplay [Of Early Spring] at 1:30 PM. Started on March 30th. It took us 87 days to finish it. We celebrated with Brandy. I was dead-drunk.”

Saturday, January 3rd, 1959.

“Memo: Drink in moderation! Don’t work too much! Don’t nap too much. Remember there is not much time left to live.”

Wednesday, March 4, 1959.

“Hangover and headaches”.

Saturday, April 16th, 1960.

“Bath. Prepared myself a broth with konbu [sort of seaweed]. The screenplay [of Late Autumn] progressed a little. In the evening, drank some Hennessy and ate a piece of cheese. Delicious! Nothing better than life can offer!”

In April 1963, Ozu is diagnosed with cancer and hospitalized at the Tsujiki National Treatment Center.

Tuesday, April 23, 1963.

“Cobalt treatment.”

Monday, July 1st, 1963.

“I left the hospital after eighty-three days.”

Ozu’s last entry is dated August 14, marking the end of these invaluable Journals. He died on December 12, on his birthday. Flipping one last time through the pages, here is another moving aphorism from December 1st, 1933: “One climbs the mountain, knowing you will have to come down and one goes on a journey knowing you will have to return to your departure point. Turns and detours along the way will have enriched your life experience. A is only A. Essential is the path traveled between B and Z.”

His grave is located at the Engaku-ji Temple in Kamakura where he has lived since 1953. A black tombstone is simply carved with the character mu. It means nothingness …To pay homage, visitors often leave bottles of sake and liquor at the site.