- Industry

Filmmakers’ Autobiographies: Preston Sturges on Preston Sturges

“(The) only amazing thing about my career in Hollywood is that I ever had one at all.”

This is the bittersweet confession made by Preston Sturges, midway through his unfinished autobiography, published in 1990, 31 years after his death.

When he came to finally direct his first film for Paramount, The Great McGinty in 1940, a morality tale comedy and political satire about corruption in American civil life, Sturges was 42 and he had been working in Hollywood as a screenwriter for close to ten years. He had sold this script to the studio for 10 dollars, just to be able to direct it, and have total control, a rarity in those days. He won the Best Original Screenplay Academy Award for it and was soon on a roll.

In the next four years, he would helm an astonishing total of six more pictures, most of them considered classics today, some the best screwballs comedies ever made: Christmas in July, The Lady Eve, Sullivan’s Travels, The Palm Beach Story, The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek, where Claudette Colbert, Betty Hutton, Barbara Stanwyck, Joel McCrea, Veronika Lake, Henry Fonda, Dick Powell, all had memorable parts.

His name is synonymous with a uniquely caustic and witty type of entertainment, the winning mix of madcap American energy and brashness combined with European piquancy and sophistication. But his meteoric rise would soon be hampered by setbacks and disillusions.

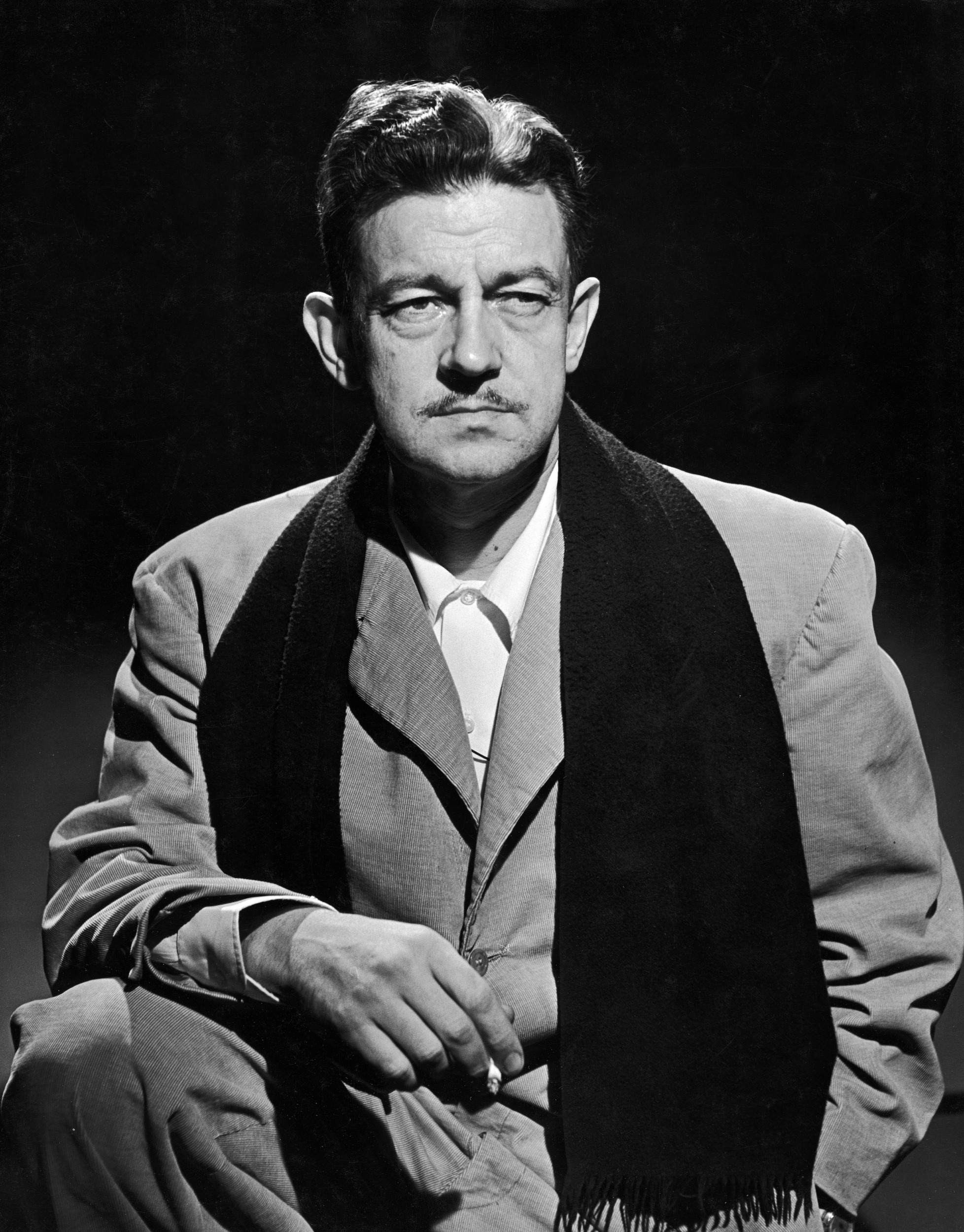

(Top) Robert Taylor visits Sturges on the set of The Great McGinty, 1939; J.A. Krug, chairman of the War Production Board, Frances Ramsden, and Preston Sturges on the set of The Sin of Harold Diddlebrock, 1945; (bottom) script read for The Lady Eve with Barbara Stanwyck and Henry Fonda, 1940.

john springer collection/bettman/getty images

Leaving Paramount in 1944 was the first stumble. Then, his tempestuous partnership in an independent production company with the controlling Howard Hughes quickly went sour, crushing his dream of creative and financial independence. By 1948, he explains, “the enormous flops of my last two pictures had greatly damaged my own value in the motion picture industry.” Suddenly, he could not find work as a writer-director-producer anymore. His reputation for being too expensive and hard to handle made it difficult for him to be hired by studios. Mainly, he argues, because of “the wracking disappointments I encountered in having got into a position where, to survive, I had to deal with fools, liars and shaky amateurs.”

He tried to go back to scriptwriting, all the while injecting most of his money to revamp The Players, his once-popular restaurant on the Sunset Strip adjacent to the Chateau Marmont, into a theater by adding a revolving stage. “Before it sank under the weight of four mortgages and accumulated debts.”

In 1952, an unexpected offer, after many that never materialized, (like an adaptation of George Bernard Shaw’s The Millionairess with Katharine Hepburn), came from the French production company Gaumont. He moved to Paris to direct Les Carnets du Major Thompson, a farcical comedy starring Noël-Noël and sex-symbol Martine Carol. It was released in May 1957 in America, retitled The French, They Are a Funny Race. Critics dismissed it. Audiences stayed away. It would be his last film. Not the swan song he deserved. Once again, at a critical crossroad career-wise, Sturges struggled to find work .“I have always contended that in addition to talent, success depends on a little bit of luck,” he writes, “and my luck seemed to have run out, professionally at least.”

Still eternally optimistic, he persevered, even if, as he noted, “1958 did much to destroy the conviction that I could write my way out of trouble. I still had two of the best plays I have ever written on hand, and despite signed contracts, false starts and heartbreak, just 136 dollars total in the bank.”

Paddling around his swimming pool in his son’s toy row boat, Los Angeles, 1944.

Ralph Crane/Condé Nast via Getty Images

A much-needed break came when, in February 1959, he got a large advance to write his autobiography. Warning it was to be “in no sense a farewell to the world.” But the lucid account of quite a colorful life that he sees, looking back upon it at its twilight, as an endless “Mardi Gras, a street parade of masked, drunken, hysterical, laughing, disguised, carnal, innocent, and perspiring humanity of all sexes, wandering aimlessly, but always in a circle.”

A good two-thirds of the book details his very bohemian and cosmopolitan upbringing. Starting with the influence of an eccentric and resourceful mother, Mary, who made believe she belonged to the Italian aristocracy. “She was in no sense a liar,” he remarks drolly, “nor even intentionally acquainted with the truth.” From an early age, she dragged along young Preston in her peripatetic escapades between America and the continent. Settling temporarily in Paris, Berlin, Bayreuth, Deauville, or the Riviera, to peddle the beauty products of her boutique Maison Desti, but more often to join her closest friend, the famed dancer Isadora Duncan and a cohort of wealthy acquaintances and suitors, some she would marry.

As for his education, the boy was put in various boarding schools, in France and in Switzerland. As a result, he spoke better French than English. It was a world straight out of an Edith Wharton novel, with a dash of the carefree fatalism haunting some of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s effervescent tales of the Jazz Age. It would later provide ample inspirations for some of the zany characters and situations in his pictures…

In 1919, back to civilian life after a stint in the army, now living in New York, Sturges had no clue of a definite line of work. He held various jobs, one of them was to handle his wayward mother’s business, for whom he invented a “kissproof” lipstick! One evening in 1929, he had an epiphany after taking a girlfriend to see a play on Broadway. He bet he could write one! He did and got noticed for it.

A second one, Strictly Dishonorable, was a hit. He made $ 300,000 and spent it all quickly. Paramount asked him to write a script for a Maurice Chevalier vehicle, The Big Pond. More followed in rapid succession. Three years later, he moved to Hollywood, as he explains, “starting at the bottom at Universal, working in a team with other writers, like piano movers!” After watching directors adapt his material and dialogues for the screen, more often than not, not to his liking and vision, he was determined to prove he could do it better himself. That would not happen overnight…

When the book is published Sturges was largely forgotten, unlike his still active and more revered contemporaries, Frank Capra, George Cukor, or William Wyler. That makes its reading more poignant beyond the many hilariously entertaining parts. In prose often infused with melancholy, he recounts his quest to recapture the elusive brass ring that had made him rich and famous in the 1930s and 40s. The hardship to pick up the pieces and reboot once more what had been a fertile and lucrative but short career. Under the elegant varnish of his breezy, insouciant storytelling permeates the aching prescience that it was never to be. Admitting being to this day as inexperienced and impulsive as he was at 16, he finds solace knowing that “my life, even in those disagreeable trying times, is complete.”

His writing was abruptly interrupted on August 6th, 1959, the day he died of a heart attack at age 60, in a room at the Algonquin Hotel in New York. Alone. 20 minutes earlier, he had jotted down the last sentence.