- Film

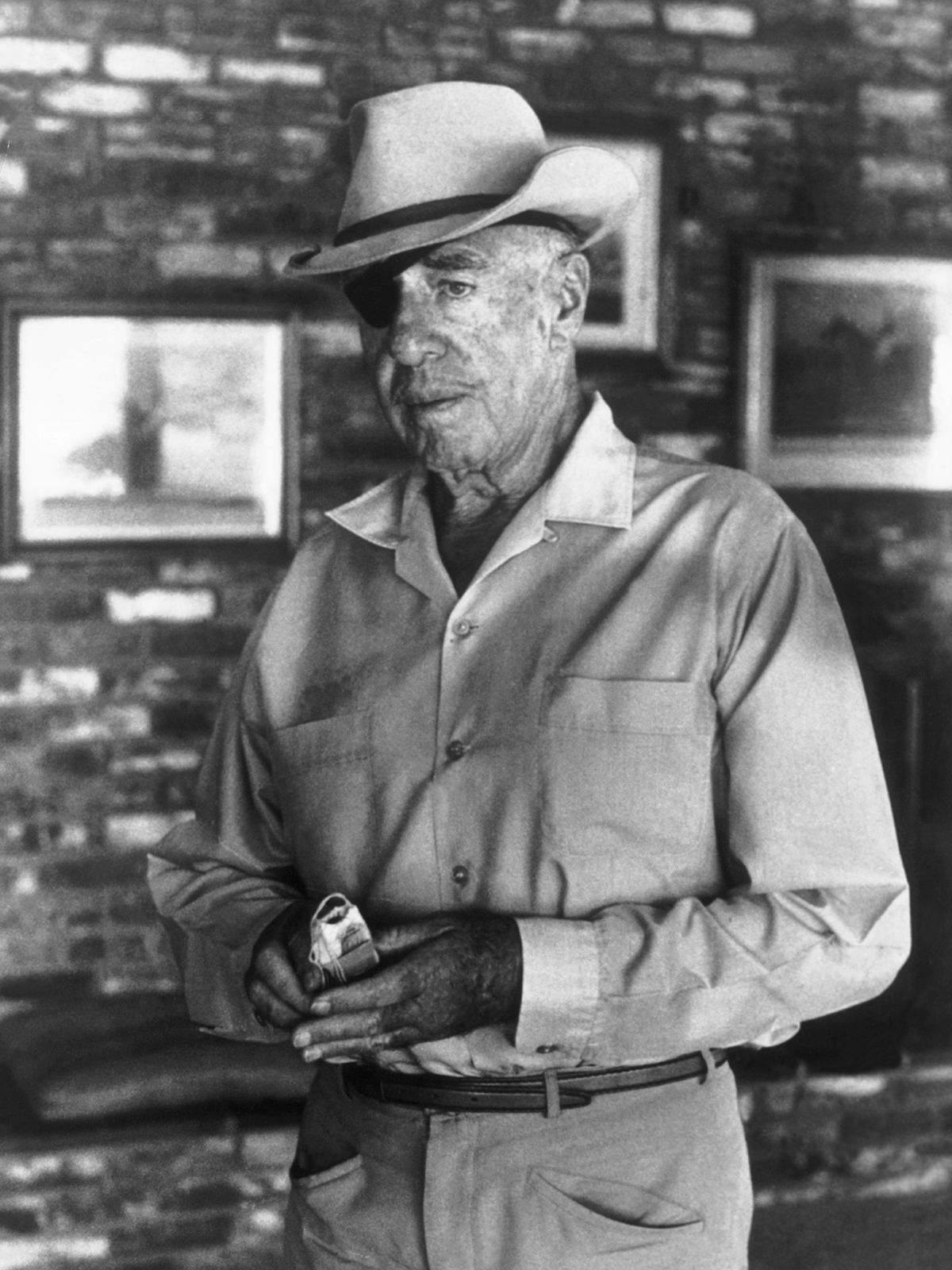

Filmmakers’ Autobiographies: Raoul Walsh – “Each Man in His Time”

“I saw its birth, its golden era, and its declining years and I am convinced that Hollywood’s decline from glory is in no way the result of senility. On the contrary, it is a relapse (temporary, I hope), into the immaturity of adolescence.” So laments eighty-six-year-old Raoul Walsh in his memoirs, titled “Each Man in His Time”, published in 1974.

As he embarks with the reader on an often-galvanic ride down memory lane, he cannot help but state his doubts towards the state of American cinema in the mid-seventies. After all, as one of the pioneer directors who helped build the Dream Factory, he had seen it all in a fifty-year-long career that ended in 1964, with more than one hundred films to his credit. So, he feels it is time to tell his story first hand and remind a new generation that might have forgotten him of his achievements and his pivotal place in Hollywood history. Even if sometimes it means embellishing it along the way with some tall tales, it is nonetheless highly entertaining. Walsh obviously knew that spicing up his autobiography with some outlandish claims would only enhance his legend as a rousing maverick having lived an extraordinary and highly colorful existence. Posing as a picaresque raconteur, he relished nothing more than presenting a larger-than-life roguish persona, gambling aficionado, horse fanatic, great estimator of the outdoors as well as bedroom activities.

“Memory, like luck, can be a fickle jade,” he writes. “Things that happened only yesterday have a habit of hiding while events that occurred eighty years ago will still be fresh in one’s mind.”

He clearly remembers his privileged New York upbringing in a well-to-do family: the many illustrious visitors, amongst them Buffalo Bill Cody and Western painter Frederic Remington. Listening to their stories, he fantasized about being a cowboy, responding one day to the call of the West, “fighting red men in the prairie.” He mentions the death of his mother when he was fifteen. With her, he had seen his first movie, The Great Train Robbery at a Broadway Nickelodeon. He recalls the irrepressible need to leave home, the longing for other horizons, the thirst for adventure. A trip to Havana on his uncle’s schooner was the first step. The next stop was Veracruz, Mexico and then Galveston from where he joined a cattle drive up north along the Texas trail, shepherding a herd of six hundred longhorns. A drifter with no roots, he later found work as a horse-breaker, gravedigger, anesthetist and cowhand.

In 1905 in San Antonio, a local theater production needed a cowboy to ride a horse onstage. He volunteered and was hired. Bitten by the acting bug, he soon craved more. “I read scripts and sat up late, waiting for fame to knock at my door. I might have felt more encouraged if I had known that opportunity would arrive when the time was right.” Back in New York, his good looks got him cameos in two-reelers, first for Pathé Film and then for Biograph where he met D.W. Griffith and appeared in films alongside Blanche Sweet, Lillian Gish, Lionel Barrymore. By 1913, he had joined Griffith’s newly formed Fine Arts Studios in Hollywood. At the corner of Vermont and Sunset Boulevard, Walsh recalls “the big outdoor stage, an open-air structure, with movable props and backdrops like a theater stage and diffusion screens to control and distribute the sunlight. (…) this was the first studio, roofless platforms with no indoor stages, cluttered with all the paraphernalia of early moviemaking.”

A year later, Griffith sent him to Mexico for several weeks to capture footage of Pancho Villa and his army of rebel soldiers during the country’s revolution that would be part of his next feature, The Life of General Villa. A hair-raising experience that Walsh relished. “It was an epic, a bloody one, violent and filled with rapine.” Griffith was pleased with the coverage, and Walsh even got congratulated by Jack London and Wyatt Earp who showed up one day at the studio. Then it was back to acting that same year with Walsh playing John Wilkes Booth in the Lincoln assassination sequence of Birth of a Nation.

Griffith felt his protégé was ready to be a full-fledged director and Walsh would always make sure to apply his mentor’s methods. “A good director must be able to inspire whoever he was coaching so that the actor would live the scene. Make-believe must become reality.” He was quickly assigned project after project, churning out films that helped establish him as proficient, reliable and fast.

In 1924, Douglas Fairbanks chose him to helm The Thief of Bagdad which displayed his effervescent acrobatics to maximum effect and included some spectacular sequences like the groundbreaking flying carpet. Walsh was legitimately proud of its resounding success.

He switched genre with What Price Glory? in which “the story’s earthy dialogue and army and Marine profanity were every bit as important as the action.” Another hit. “The public must have been waiting for a picture to debunk war,” he remarks.

In 1928, while in the midst of directing In Old Arizona, in which he was also playing the Cisco Kid, he lost this right eye in an automobile accident. Never dwelling on his misfortune, (“The world was not going to stop because of it. I could still ride and dance and order a drink.”), he simply chose to wear a trademark eye patch for the rest of his life. Two years later, he cast an unknown John Wayne in The Big Trail, the first big-budget widescreen production of the sound era, filmed entirely on location. In the part of a frontiersman, “his height gave him authority and his voice was developing the familiar twang that would be expected by millions. He took directions easily and I never had any trouble keeping him in character. In the jargon of the trade, he was a natural. There is a lot of pride in the knowledge I discovered a winner. Not only that. I also found a great American.” Over the next three decades, Walsh was under contract mostly at Warner Bros. where he made several memorable pictures. The Roaring Twenties, High Sierra, They Drive by Night, White Heat, Objective Burma, They Died with Their Boots On, Distant Drums…Violent thriller, gritty film noir, hard-hitting western, exotic adventure, war drama, romance, even musical, he tackled it all with the same crafted efficiency. Giving some of their most enthralling parts to Humphrey Bogart, James Cagney, Gary Cooper, Kirk Douglas, Clark Gable, Robert Mitchum, George Raft. He directed seven films with Errol Flynn with whom he was close until his death in 1959.

Once, when William Randolph Hearst complimented him on his versatility, he responded: “I had a sudden puckish impulse to tell him that I was seriously considering directing Little Red Riding Hood!” Kidding apart, Walsh knew what worked best for him, always willing to push boundaries on screen. “We were never the lotus-eaters of legend,” he insists. “We performed an endless job of hard work under hot lights and blazing sun, in rain and snow or wherever the job took us.”

His account of a trip to Nazi Germany in 1936 provides a priceless anecdote, probably apocryphal. One evening, he attended a representation of Die Walküre at the Berlin Opera where Hitler happened to be present. Looking back, Walsh cannot help but muse that “I could have worked my way to his box as I did when I shot President Lincoln in The Birth of a Nation, leaping to the stage and yelling Sic semper tyrannis. I would have been caught and executed, but I know now that I would have saved the world great suffering and the loss of millions of lives this monster caused.” In retrospect, changing the course of history did not seem so far-fetched for his robust ego. After all, didn’t he once give the brush off to Bugsy Siegel, refusing to participate in a business deal offered by the infamous gangster?

He boasts about his well-known womanizing, conveniently forgetting to mention his two first wives. “I did my share of shepherding Hollywood pretties in the direction of the casting couch, but they were some other director’s meat and potatoes, not mine. All of them were luscious and transient; that was what I wanted.” He fell for Gloria Swanson while directing her in Sadie Thompson. But he resisted the temptation of an affair. “Becoming involved with female stars beyond what the script calls for is something every sensible director learns to avoid like poison ivy,” he warns. “If he indulges his amatory appetite, he is liable to discover that the star has become his boss and is busy directing him.”

He concludes his memoirs by reminiscing about the end of the studio system, the passing of his movie stars friends, the twilight of Hollywood, “that mythical abstraction, without geographical boundaries…” Still energized and opinionated, he makes sure to send one last strong message. “It is my optimistic hope that a new generation of filmmakers will outgrow this preoccupation with animated graffiti, and learn the ABC of entertainment, which is at least the basis of that rare commodity, art.”

As Gregory Peck writes on the back cover of the book, “it presents the time and life of Raoul Walsh, the literate, colorful roughneck, whose commercial movies of the last five decades are now being recognized as film art. It is a rousing social record of high old times, and a fascinating personal story of one of the last of nature’s noblemen.” One that belonged to a breed of filmmakers, long gone and never replaced, like John Ford, Howard Hawks, Allan Dwan, William A. Wellman…They don’t make them like that anymore.