- Film

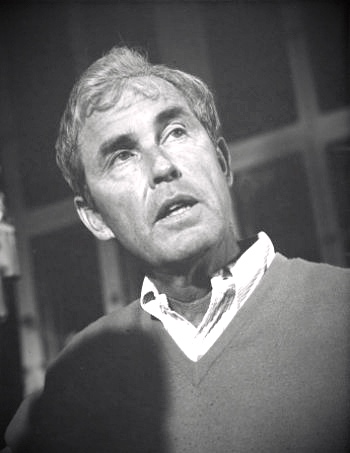

Filmmakers’ Autobiographies Robert Parrish, a True Hollywood Child

Film Bios is an occasional series reviewing autobiographies of notable filmmakers.

It was 1926 when Robert Parrish saw Douglas Fairbanks in The Black Pirate. As a ten-year-old, he watched, transfixed, the dashing mustached star spectacularly sliding down the ship sail by simply cutting through it with a knife in one hand all the way to the deck. Back home, the boy could not wait to replicate the stunt in the family backyard. A kitchen knife and a sheet suspended from a tree branch would do! But with a different result: a bloody nose and a broken arm!

This is one of the many colorful stories told by the director in his first autobiography Growing Up in Hollywood, published in 1976. 12 years later he would add another volume to his memoirs, the equally entertaining Hollywood Doesn’t Live Here Anymore.

Today, 23 years after his death, Robert Parrish’s name is rarely mentioned amongst the most prevalent filmmakers of the golden age of Hollywood during which he directed most of his film – only 19 in total from 1951 to 1974. Surely, he never reached the cult status held by some of his contemporaries like Hitchcock, John Huston, Minnelli, Douglas Sirk, George Stevens, Fred Zinnemann, Otto Preminger or Billy Wilder. He was fine with it, simply assessing his career with a refreshing openness. “I directed and produced some films that I liked and, as one critic wrote some that are easily forgettable, but with one exception a film I thoroughly disliked, I enjoyed almost every minute of every film.” In the end, what happened behind the scenes is often more interesting than most of the films themselves. The books make for captivating reading because the author is a splendid storyteller in covering his recent and not so recent past. Even being compared to Mark Twain by his friend Bertrand Tavernier with whom he co-directed the 1983 documentary Mississippi Blues.

Written in a breezy style and an often deadpan sense of humor, these memoirs are a real page-turner. As one British reviewer opined “one wonders if he hasn’t been in the wrong business all along.”

For Parrish, a true child of tinsel town indeed, it all started when his mother had him, his brother and two sisters hired as extras. It was still the silent era and the brood would soon be working regularly. By 1926, Parrish had appeared in several films by John Ford and Cecil B. deMille, the latter “probably gave work to more extras than any other directors. I worked for him many times in large crowd scenes. Sometimes I was so far back I wouldn’t actually see his face, only a figure in riding pants and puttees, with a large megaphone hiding him from the shoulders up. He was the caricature of the tyrannical movie director. Crowds (and seas) parted when he approached. He carried a riding crop which I never saw him use on a star, but I did see him use it on the man whose sole job was to carry a chair around and slip it under the royal bottom wherever deMille chose to sit.”

In 1931, on the set of City Lights. Robert Parrish is the first newsboy on the left, wearing the white newsboy style cap.

john kobal foundation/getty images

In 1931, Parrish, then 15, recalls, “Charlie Chaplin’s casting director came right into our schoolroom and asked who would like to work in a movie called City Lights”. Parrish and a mate were selected to play newsboys in a scene where they had to shoot peas through a peashooter at the Tramp. So here we are on set with him, as he describes Chaplin’s antics at mimicking what he expects from the boys and all the other actors, acting all the parts. “He said he found it best to show people rather than tell them.” Witnessing the comic genius at work, Parrish had found his calling. “After my experience on the film, I had one but permanent ambition- to be a movie director.”

He would just have to wait thirty years to see his dream come true with The Mob.

At 18, he resented being what was then called a stock actor. “It seemed a dumb job to me. We put thick grease-paint makeup and stood reacting in the background. We were herded around like sheep, yelled at like cattle and regarded as necessary evils. We weren’t really actors. I hated it. We couldn’t even get a tan through the make-up.”

He found himself quite disillusioned with it all. “The whole movie business was an illusion, dreams on inflammable nitrate celluloid that disappeared immediately after they were flashed on a blank screen.”

His goal to become a director was more pressing than ever. He asked John Ford for advice. His response? “The cutting room is where you learn about directing.” And Parrish listened, apprenticing on several films in such capacity, ending up winning the best editing Oscar for Body and Soul directed by Robert Rossen in 1947. And anytime he could he would sneak on the set to watch Ford direct, whether it was on The Informer, The Grapes of Wrath or The Long Voyage Home, he kept asking him about filmmaking or what made John Wayne so special.

No wonder the many pages dedicated to Ford. It was early 1973 when he saw him one last time. The legend, terminally ill, had just moved to Palm Desert, and he found him in bed, rummaging through a plastic bucket half full of old cigars butts, remarkably alert but very thin. “All his Oscars had been laid on a table, along with miniature ones to match each one of the originals, a golden forest.” Parrish was told he would be granted only five minutes. He got one hour. Ample time to pay his respects to the man who had been such a major inspiration, mentor and friend for close to 50 years. They could reminisce about the movies they had worked on together, their time during World War II and the OSS, the challenges of The Battle of Midway…“We talked about zoom lenses (he did not approve), John Wayne (he approved), Hank Fonda (he approved). He asked if I had won another Oscar and told him I hadn’t and he said: “It turns out they are not as unimportant as I thought.” Ford passed away in August of that year.

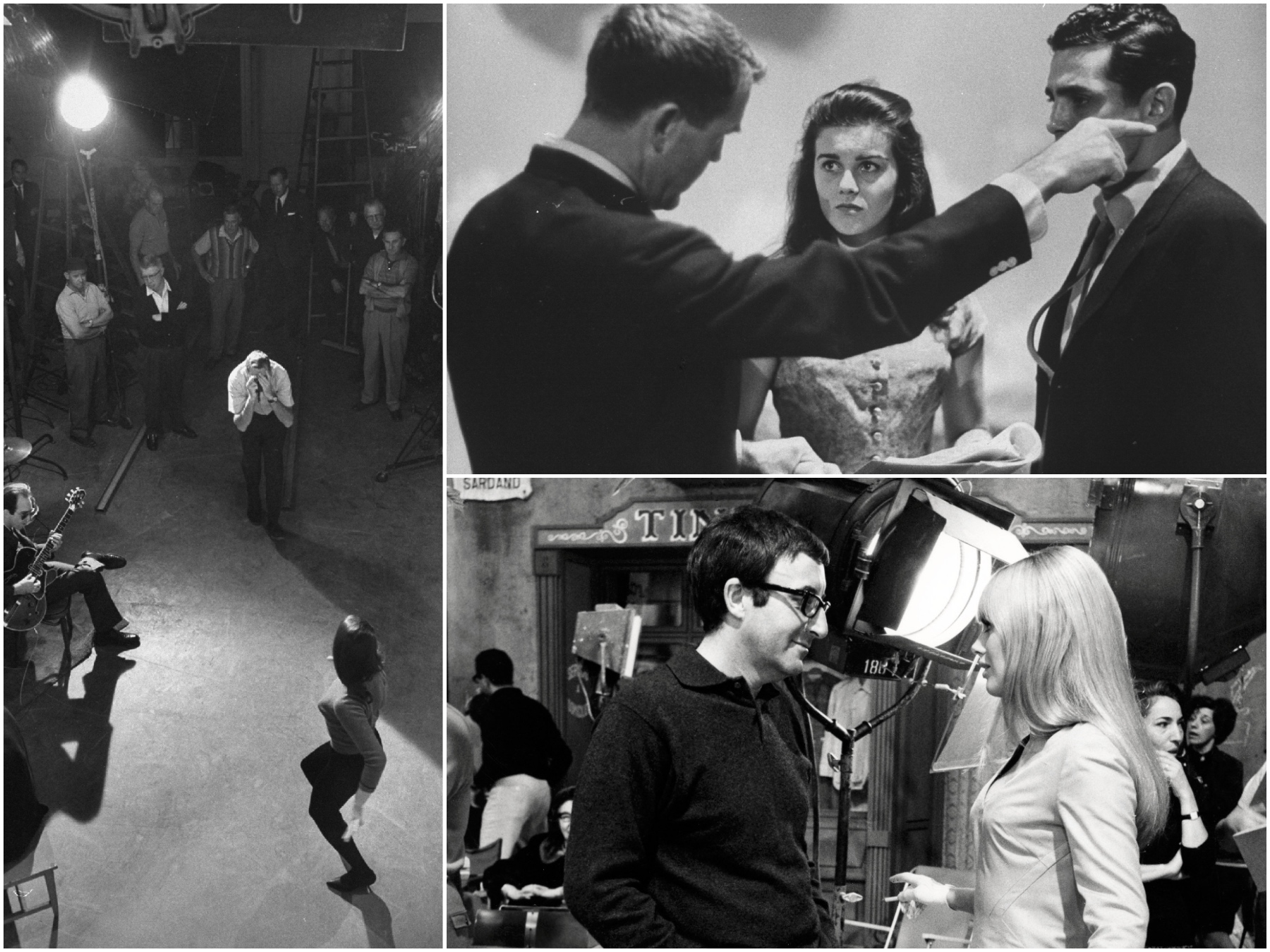

(Left) Parrish rehearses a musical number for the movie State Fair with 18-year-old Ann-Margret Olson, on the 20th Century Fox lot; (top right) in 1961, prepping Ann-Margret for her screen test; (bottom right) Peter Sellers and Brit Ekland on the set of The Bobo, 1967.

grey villet/the LIFE picture collection/moviepix/getty images

Anecdotes abound on actors he directed. John Garfield, Rita Hayworth, Gregory Peck (he saved him from venomous snakes while on location for The Purple Rain in the jungle of Ceylon, now Sri Lanka), Robert Mitchum, Jean Seberg. Parrish talks movingly about his long-lasting friendship with Irwin Shaw, Peter Viertel and of their many gatherings through the years in Klosters, the Swiss mountain town where many of the Hollywood expatriates liked to sojourn. Two encounters in the early 50s with Ernest Hemingway are vividly rendered. With their wives, they attend bullfights in Spain, talk about the traps of writing for the movies, indulge in many libations involving local wines and their respective merits.

He writes about settling in London in the early 60s, lured there by Sam Spiegel (On the Waterfront, Lawrence of Arabia), “the wiliest, most intriguing, most skillful of all the producers I worked with.” The project never materialized but Parrish stayed in England where he would spend the next twenty years. His European period was a globally satisfying one even “when the pictures that I was involved in became progressively less interesting.” One of them is Up From the Beach. Parrish amusingly recalls that Darryl F. Zanuck produced it “primarily because he had thousands of feet leftover from his hit war picture The Longest Day, and even more primarily because we had a girl in the film that he likes to visit on our Normandy locations and that he was grooming for stardom.” He doesn’t give away the name but it was Irina Demick, one of the many forgotten starlets of a bygone era.

He has no fond memories for Casino Royale (1967), “a bastardized episodic parody of Ian Fleming’s James Bond” for which he directed one segment involving Orson Welles and Peter Sellers. His comment? “The first picture I directed where the two leading players wouldn’t speak to each other, a situation that kept me on my toes and my hand on the aspirin bottle.” He had troubles again with Sellers soon after on their next film, The Bobo. “After three weeks shooting in Rome, Peter called me aside and whispered: “I’m not coming back after lunch if that bitch is on the set.” He was talking about his co-star and then-wife Britt Ekland. Quite a headache.

His last film would be The Marseille Contract in 1974. “It was a pleasure working with James Mason, Michael Caine, and Anthony Quinn. We all tried, but sometimes you win, and sometimes you lose.” On that film, he relishes telling how, during the location shoot in Paris, the panicked English producer was only obsessed with securing as many rolls of French toilet papers for fear of an alleged shortage in England, and never once seemed concerned with the movie itself!

In Hollywood Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, an obviously nostalgic Parrish has a chapter called “the past is a good place to visit.” For the reader, it’s a treat to follow such a first-rate guide down memory lane.