- Film

Filmmakers’ Autobiographies: Samuel Fuller, A Third Face

By 1995, Samuel Fuller was back in his Hollywood Hills house at 7628 Woodrow Wilson Drive, after a 13-year self-imposed exile in Paris. At 83, he had just survived a debilitating stroke. So, for the next two years, until his death, he dedicated most of his time to completing his autobiography. Boasting that “my life is a helluva tale and I’ve one more great yarn to tell: my own.” Which indeed he did in the breathlessly absorbing “A Third Face: My Tale of Writing, Fighting and Filmmaking”, published posthumously in 2002.

The impassioned foreword by his fervent admirer Martin Scorsese, instructs the reader thusly: “If you don’t like the films of Sam Fuller, then you just don’t like cinema. His movies are blunt, pulpy, occasionally crude, lacking any sense of delicacy or subtlety. But those are not shortcomings. They are simply reflections of his temperament, his journalistic training, and his sense of urgency.” Scorsese’s words perfectly sum up the personality of one of Hollywood’s most unique mavericks and iconoclasts.

“Writing has always been my first calling,” Fuller remembers. Though nothing in his upbringing in Worcester, Massachusetts where he was born, could foretell it being the essential driving force that fueled his career from the start. At 12 years old, while still attending school in New York, and in order to help his recently widowed mother and siblings, he made a few dollars selling newspapers. One of them was William Randolph Hearst’s Evening Journal, where he soon got a job as a copyboy. From then on, he was hooked on the intoxicating journalistic world of Park Row. “My all-consuming ambition was to be a crime reporter with my own byline.”

At 17, he got his wish, “thanks to my ability to write punchy prose and my nose for news,” working the beat for the newly launched New York Evening Graphic. There, he learned the ropes with the more seasoned Rhea Gore, mother of John Huston. His very first scoop was reporting the death by overdose of movie and stage star Jeanne Eagels. Those were heady times. The salad days “in the bustling, effervescent Manhattan of the roaring Twenties,” hanging out in speakeasies and smoking cigars with Ring Lardner and Damon Runyon.

In 1931, he followed Horace Greely’s famous apocryphal exhortation to “Go West, young man.” Working as an itinerant freelancer, he went on “zigzagging across the country by hitching rides on any truck or freight train that was going my way, my Royal typewriter tied to my backpack with a cord.” Witnessing first-hand the effect of the Great Depression that swept the nation.

Fast forward to 1938. With three published novels, and “plenty of yarns up my sleeve, I decided to finally take a serious dip in Hollywood’s seductive waters.” He first got a job ghostwriting. “An established screenwriter would get credit for my work,” he explains. “The money was good, but I had to promise never to discuss my participation. That was my screenwriting school. My writer friends used to try to guess the names of the movies I’d worked on. It was one of their favorite games over martinis at Musso & Frank’s.” He would never tell, and not even in this autobiography, almost 60 years later.

“Hell, it was damn hard work,” he muses. “As a novice in Hollywood, I took every assignment that came my way. I learned the basics from the ground up. In journalism and fiction, you rely more in description to propel your story. Movies are about action, conflict, and sharp dialogue. Eventually, screenwriting became a second nature to me.” He made sure to study the best, impressed by Mervyn LeRoy’s I Am a Fugitive From a Chain Gang, Michael Curtiz’s Black Fury, William Wellman’s The Ox-Bow Incident, and his favorite, John Ford’s The Informer. He writes about his enduring friendships with the latter, and others he looked up to, Frank Capra, Howard Hawks, Raoul Walsh.

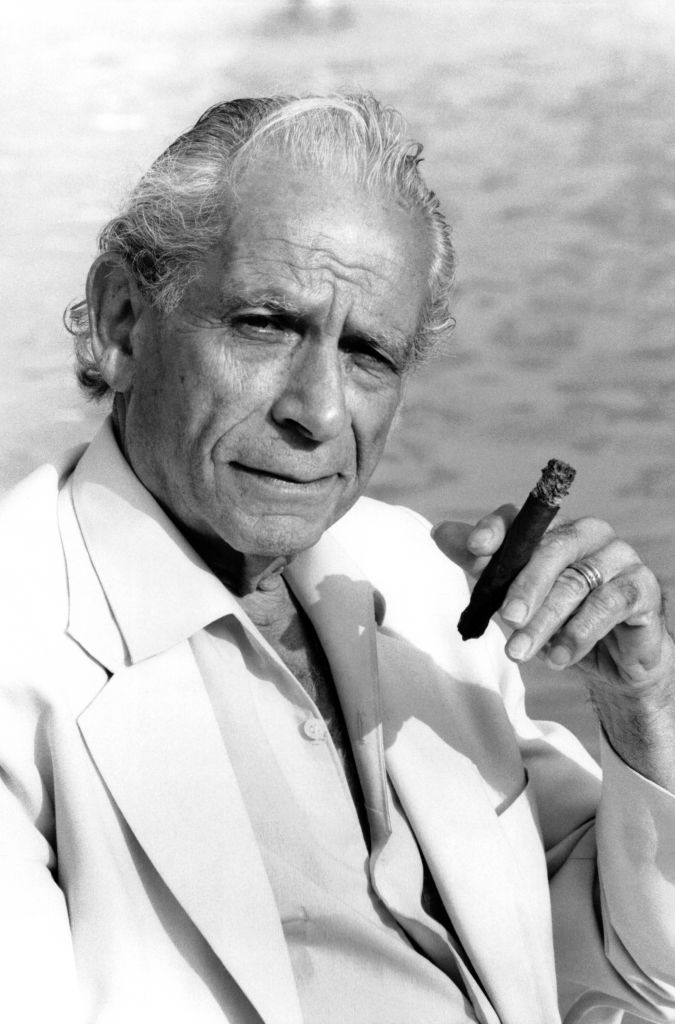

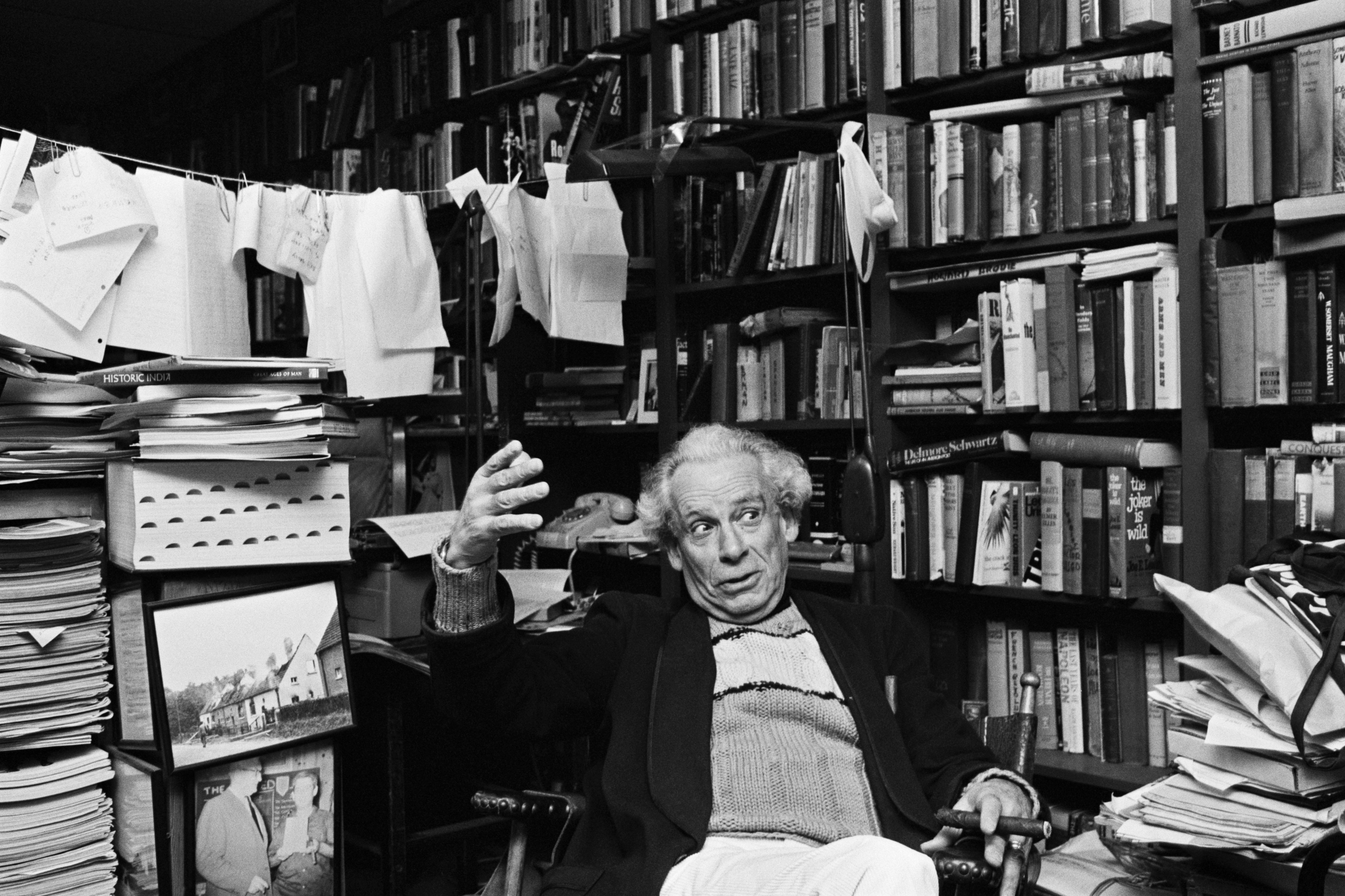

In his office, 1980.

Caterine Milinaire/Sygma via Getty Images

Once the United States entered the war, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Fuller enlisted in the Army. “The scripts I was doing in Hollywood, my plan to try directing, all of it suddenly seemed unimportant. Nothing was going to stop me from being an eyewitness to the greatest crime of the century.” Assigned to the 1st Infantry Division, he was sent to the North African front and then participated in the invasion of Sicily. He knew that “guys came back from the war one of the three ways: dead, wounded or crazy.” He was stunned to make it alive after landing on Omaha Beach in Normandy on June 6th, 1944. A hair-raising experience he would recreate to maximum impact in 1980 with The Big Red One.

The return to civil life meant a new chapter. He went back to Hollywood, churning out many scripts, confident “that I could direct my own yarns as well as anybody else. Maybe even better.” His first movie, I Shot Jesse James, in 1948, proved it. Deliberately eschewing the traditional elements of the genre, because, as he admits, “making just another Western wasn’t going to give me a hard-on.” Playing with the codes and twisting them would often be at the core of the 25 more films that followed in the next 42 years.

His directing career proved equally versatile, unpredictable, and provocative. Tackling an impressive diversity of themes, racism, sexual perversion, patriotism, insanity, violence, in films like Steel Helmets, Hell and High Water, Run of the Arrow, China Gate, Verboten!, Underworld U.S.A., Shock Corridor, The Naked Kiss. “One of the truths about human existence is the struggle to be free of boundaries, real or emotional. Almost all my movies touch on that idea one way or another.” Even if he admits that sometimes the message “had the subtlety of a sledgehammer.” No wonder he relishes reminding us of what Jean-Luc Godard made him so appropriately utter in Pierrot Le Fou, where he played himself in a memorable cameo. “Film is like a battleground. Love, hate, action, violence, death. In one word, emotion.” With Fuller, it would most often be achieved in a gut-wrenching way.

The book almost bursts at the seams with numerous anecdotes about all those pictures and more. So many, colorfully told with humor, at time laced with borderline hard-boiled cynicism, always in his typical energetic prose and fast-paced tempo. He tells about his relationships with Darryl F. Zanuck, of his pitching sessions with the 20th Century Fox mogul in his office where hunting trophies hung on the wall and their shared love of cigars. “He was always a straight-shooter, unflinchingly supportive and fair, even when we disagreed. Over the years, I did plenty of pictures with him. We had a great working relationship.” Nonetheless, he turned down several Zanuck’s prestige projects like The Desert Rats, The Young Lions, and The Longest Day. His excuses? “I could not see myself mixed up with those overblown, glaringly inaccurate Hollywood productions.” He had to do it his way….

In 1951, he cast an unknown James Dean in his first film, Fixed Bayonets. “I liked his face and gave him a crack and hoped it would bring him luck.” Two years later, Marilyn Monroe begged him to give her the part of Candy in Pick Up on South Street. “She did not speak, she purred. I told her straight that if she walked along my decrepit waterfront in the film, her overwhelming sensuality would obscure my yarn. She was so disappointed. I said we’d look for another picture to do together.” He recalls how, too tired after a long day at the typewriter, he could not attend a little get-together Sharon Tate was having at her place on Cielo Drive. It was on the fateful night of August 9th, 1969. For a while, in the early 70s, an eager Jim Morrison was a frequent visitor to the Shack, as he called his house, “discussing poetry and movies.”

In 1982, White Dog marked another turning point in Fuller’s career. Paramount offered him to adapt Romain Gary’s novella, about the failed attempt to rehabilitate a canine that has been trained to only attack black people. Even before it was released, Fuller was flummoxed to learn that “rumors began to circulate that it was a racist movie.” Fearing a backlash or worse, that it would incite race violence, Paramount’s studios heads Michael Eisner and Jeffrey Katzenberg shelved the film. It would have to wait ten years before an American release.

Deeply hurt, Fuller moved to France. He never made another film in Hollywood. But he kept active, writing screenplays in between directing two minor pictures that flopped. It was “a difficult period of turmoil and waste.” Many projects went burst for assorted reasons, the result of a sudden change of studio management or corporate thinking, handshake deals that went sour and broken promises. He had great hopes for his pet project about Ruth Snyder, the woman executed in the electric chair in 1928 who had inspired James M. Cain’s novel, ‘The Postman Always Rings Twice’. But even with help from his fans Scorsese and Jonathan Demme, Universal never green-lit the picture.

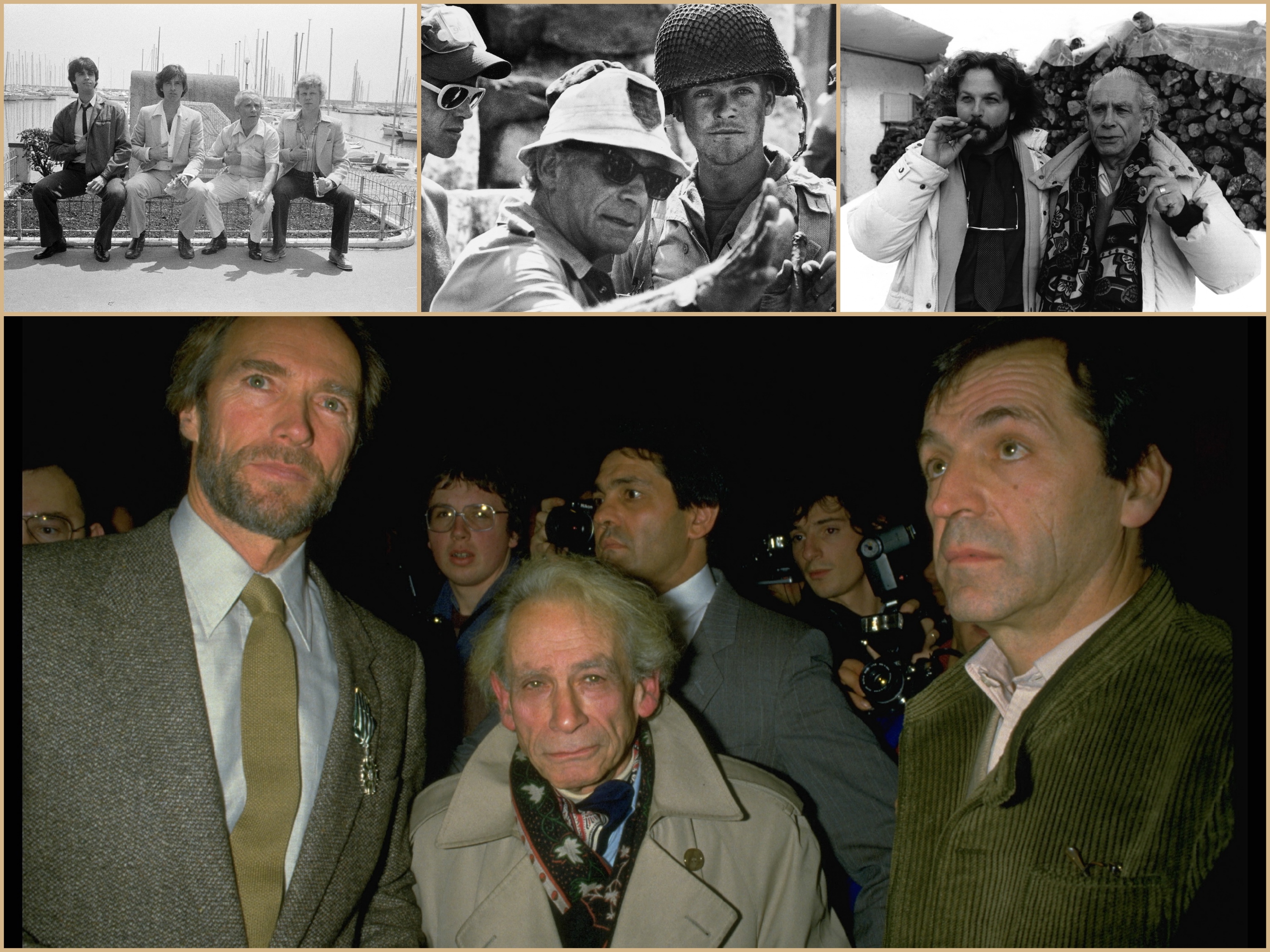

(Top, from left): At the Cannes Film Festival in 1980, with part of he cast of The Big Red One– Bobby Di Cicco, Robert Carradine and Kelly Ward; on the set of The Big Red, directing Mark Hamill, July 1978; with George Miller at the Festval du Fim Fantastique de Avoriaz, January 1983.

(Bottom): With Clint Eastwood and Constantin Costa-Gavras, at Minister of Culture in Paris, 1994.

Gysembergh Benoit/Paris Match via GettyImages; John Bryson/The LIFE Images Collection via Getty Images; Bertrand Laforet/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images; Thierry Orban/Sygma via Getty Images

In 1994, for a documentary called Tigrero: A Film That Was Never Made, Jim Jarmusch accompanied him to the Brazilian jungle of Mato Grosso, where, 40 years earlier, he had gone location scouting along the Araguaia River, spending several weeks with the Carajás tribe. At the time, he was signed to helm the eponymous adventure thriller that had all the ingredients to make what he called “a pisscutter of a movie.” But then, because of the risks, 20th Century Fox refused to insure its expensive stars John Wayne, Ava Gardner, and Tyrone Power.

Still, at the twilight of his colorful and rich existence, he kept seeing the glass “half full, not half empty.” He found comfort in the adulation and homage from a new generation of directors, Quentin Tarantino, Tim Robbins, Alexander Rockwell.

In concluding, Samuel Fuller modestly hopes that his “life story will be especially encouraging to young filmmakers trying to survive in the shark-infested waters of the movie business.” Urging them to never give up, and “persist with all your heart and energy in what you want to achieve, no matter how crazy your dreams seem to others. Believe me, you will prevail over all the naysayers and bastards who are telling you it just can’t be done…” Even if, sadly, that did not always end up being the case for him.