- Film

Filmmakers’ Autobiographies: Stanley Kramer’s Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World

“It has been more than sixty years since I came to Hollywood, first to learn how to make films and then to make them myself. I have now made thirty-five of them, some better than others, some prizewinners, other money losers. All in all, I’ve enjoyed a good career in the movie industry as a producer and director, yet not as good as my ambitions had led me to hope.”

This is Stanley Kramer’s clear-cut summing-up of his professional achievements in “A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World: My Life in Hollywood”, his autobiography published in 1997, four years before his death at the age of 87.

Priding himself in “having been able to straddle the fence between art and commerce,” he nonetheless admits it was not always easy. His producing début in 1948 with So This is New York, was, as he puts it bluntly, “a colossal failure.” Undeterred by a less than stellar start, he had no intention of quitting. He was there to stay, having come a long way from his modest upbringing as a Jewish boy growing up in Manhattan’s Hell’s Kitchen at the depth of the Great Depression, with a dream of becoming a writer. He was determined to make it in Hollywood where he had moved three years earlier, after a stint in the Army Signal Corps during the war.

Very driven and ambitious, he rarely wasted time procrastinating in selecting projects, quickly learning how to combine the requisite elements to make a film, always with a very Cartesian hands-on approach. He excelled at financing his movies independently and making them inexpensively.

He was able to work closely with directors while respecting their vision, which made for successful collaborations and a minimum of friction with the likes of Lazlo Benedek, John Cassavetes, Edward Dmytryk, Richard Fleisher, Mark Robson, and Fred Zinnemann.

He had a shrewd eye for casting, sometimes against type, and the list of actors he chose is impressive: Anthony Quinn, Fred Astaire, Humphrey Bogart, Gary Cooper, Ava Gardner, Judy Garland, Olivia de Havilland, Grace Kelly, Burt Lancaster, Vivien Leigh, Anna Magnani, Robert Mitchum, Gregory Peck, Frank Sinatra.

And Kramer has colorful anecdotes on many of them. An example with Kirk Douglas who he had selected in 1949 to play the titular character of his sophomore production Champion. Douglas plays a boxer fighting his demons in and out of the ring, Kramer selected the actor after his intense audition and virile charisma had impressed him. He was less so when, before filming began, the actor told him he just had plastic surgery on his nose which would have to be off-limits to punches for all the fight scenes!

He gave Marlon Brando his first screen role in The Men where he played a paraplegic veteran and had no problem handling him. The two would reteam four years later in The Wild One.

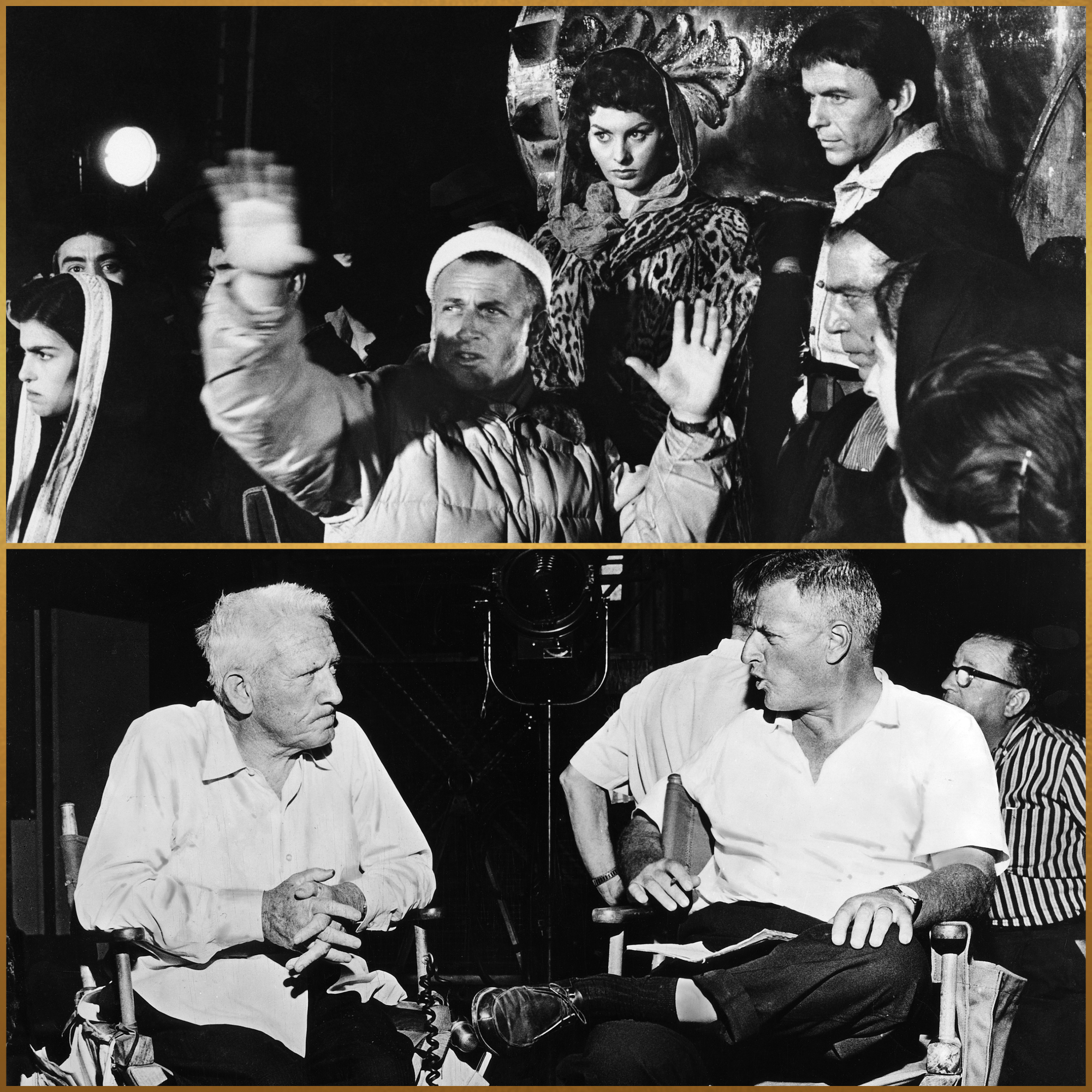

On the set: in 1957, with Frank Sinatra and Sophia Loren, The Pride and the PassionJudgement at Nuremberg.

ernst haas/ullstein bild/getty images

In 1951, Kramer made what he describes as “one of the most dangerous and foolhardy moves of my entire career when I signed a five-year contract with Columbia as an independent producer.” Knowing full well he would have to work “under the cold, sharp eye of the studio’s vulgar, domineering, semi-literate, ruthless, boorish and malevolent chief Harry Cohn.” The perfect incarnation of the crude movie mogul who invariably qualified most of Kramer‘s choices as “pieces of crap”, even though he never interfered with their making. A wild exaggeration as most of them, Death of a Salesman, The Sniper, The Member of the Wedding, The Juggler, High Noon, certainly did not merit the label.

By 1954, Kramer was longing to put an end to “the unhappiest period of my career.” After, “The Five Thousand Fingers of Dr. T brought my list of failures at Columbia to ten pictures,” he delivered one last film to the studio: The Caine Mutiny proved to be a redeeming critical and box-office success. He was now free to change gears. Frustrated as a producer, what he really wanted was to direct. “I had hired others as directors,” he explains, “yet I had never dared to hire myself.” So he finally did, simply because “it seemed like the climax to all the production work I had done, bringing the project to the shooting stage.” He chose the adaptation of a best-seller set in the medical world, Not as a Stranger. “I wish I could wax eloquent about what a thrill it was for me to sit down in the director’s chair for the first time, but the fact is I don’t remember being the least bit excited about it. The one thing about the first day is that I felt I was finally where I belonged.”

During the filming, he was unfazed by Robert Mitchum and Frank Sinatra’s mischievous antics mostly targeted towards their co-star Olivia de Havilland. “They constantly badgered her with their gags, leers and suggestive remarks and they did not hesitate to squeeze her beautiful derrière. The things they said and did to her were common on many sets in those days,” he admits sheepishly, “they were considered normal horseplay at the time. Today, you could land in prison…”

As Kramer reflects on his life in Hollywood, he takes stock of most of his films with mixed feelings. The Pride and the Passion, On the Beach, Inherit the Wind, Judgment at Nuremberg, Ship of Fools, It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World. In retrospect, he understands why some were perceived as message movies, acknowledging that their themes could have often benefited from a less heavy-handed approach. “I made four pictures about relations between whites and blacks in America”, he boasts, “each exploring a different aspect of that extremely complicated and fast-changing relationship. I came into the business at a time of great tension when racial inequality was emerging as a public issue.”. Home of the Brave (1949) was about the struggle of a traumatized black soldier to get his health back. Because of the sensitive subject, Kramer shot the film in seventeen days in total secrecy under a different title. The Defiant Ones (1958) tells the story of two escaped convicts chained together, one black, one white (Sidney Poitier and Tony Curtis), both bigoted and forced to learn how to handle their prejudices. Pressure Point (1962) confronts Poitier as a black psychiatrist with a psycho Nazi sympathizer patient played by Bobby Darin.

He is most proud of Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, because “it tackled the touchiest of all issues, interracial sex, and marriage and was the first picture ever on this subject still very much taboo in the industry.” No wonder studios were initially reluctant to greenlight such a film in 1967. But Kramer was determined to make it happen, even if it meant forfeiting his salary, counting on the prestige casting of Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn (that would be their ninth film together and their last) and Poitier.

In Los Angeles: in 1965 with Simone Signoret and Vivien Leigh at the premiere party for Ship of Fools

ron gallela/hulton archive/getty images

“Between 1967 and 1978, I made six pictures that did not do much at the box-office, for which circumstances I am almost solely to blame,” he confesses. “Each one represented a cherished dream I didn’t quite manage to put on screen as well I had seen in my mind.” The Secret of Santa Vittoria, RPM, Bless the Beasts and Children, Oklahoma Crude, The Domino Principle, and The Runner Stumbles, all misfired and demonstrated that Kramer seemed now out of touch with the New Hollywood zeitgeist, the changing tastes of the public. “It must be evident from all the above that the ’60s and ’70s represented a difficult time for me,” he concedes somewhat bitterly. “But I was as bewildered as most people by the seething confusion in society, a confusion that made itself felt in Hollywood, especially by producers who tried, as I did, to interpret society. What lasting lesson could I possibly borrow from the constant upheavals of those times? It seemed to me a proper moment to take at least a temporary leave from the industry, and maybe even a permanent one, to figure out where I should go from here.”

He moved to a Seattle suburb, wrote a column for the local newspaper, and taught classes a community college. In the end, he admits that “the one thing I wanted was to be recognized as someone who knew how to use film as a real weapon against discrimination, hatred, prejudice, and excessive power.”

That recognition is there in the foreword to the book: Sidney Poitier pays a heartfelt tribute to the director who had given him two of his most memorable roles. “The life’s work of Stanley Kramer is a testament to courage, to integrity, honesty, and determination.”