- Film

Filmmakers’ Autobiographies:Howard Hawks in the ‘Land of the Pharaohs’

Published in French in 1978, but never translated into English, Noel Howard’s Hollywood sur Nil is the fascinating account of the making of Howard Hawks’ Land of the Pharaohs, an epic production partly shot in Egypt in 1954. The author was born in Paris in 1920 and went to New York City to make it as an artist, and painter. After the end of World War II where he had served as a pilot in the US Air Force, he found himself by accident in Hollywood. There he became a researcher and historical consultant for Victor Fleming’s Joan of Arc and George Sidney’s The Three Musketeers, ( both released in 1948) for which his French background surely helped, and later with Lewis Milestone and Anatole Litvak in the same capacity. By the early fifties, he was the trusted go-between for any Hollywood studios setting up productions in Europe.

The beginning of the book finds him on the French Riviera in late summer of 1953 at Eden Roc by the pool of the Hotel du Cap and a chance encounter with a vacationing Hawks, wearing plaid swimming trunks, fresh of the box-office success of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. At some point, the director who has been gazing for a while in silence at the horizon asked out of the blue where Egypt is, before blurting out: “Noel, I am going to build a pyramid”. On the spur of the moment, he had just had the idea of his next film. By coincidence, Jack Warner has anchored his yacht in the Mediterranean a few feet away. On the spot and a few dry martinis later, a deal is sealed: the studio will finance the movie.

In an interview published in the N°56 of the Cahiers du Cinema dated February 1956, Hawks would confess to Jacques Rivette and François Truffaut that his main reason to do the film was to use the newly perfected CinemaScope format. And to help him achieve his grandiose vision he only wanted the best. Alexandre Trauner (Children of Paradise) as his art director, and to write the story and the script, his good friend Nobel Prize laureate William Faulkner for what would be their fifth collaboration, as well as seasoned screenwriter Harry Kurnitz. Noel Howard would be the second unit director. A privileged witness of the often chaotic logistical nightmares of this gigantic production. What makes Hollywood sur Nil so unique is the way this conscientious scribe takes the reader behind the scenes from an unfiltered perspective, only describing what he saw and experienced first hand. The result is a treasure trove of colorful anecdotes that illustrate the numerous excesses of the whole endeavor. From the start, you feel you are in for a very special ride.

First comes the preproduction period. Without a script yet for what would become the heavily fictionalized tale of the construction of Khufu’s pyramid, the biggest of them all. A great deal of research is done but not allowed to interfere with the filmmaker’s imagination. “We’re not making a documentary”, Hawks gently reminds Howard when told that at the time the film is set around 2560 BC, horses, rhinos and the wheel were unknown to the ancient Egyptians. Same for camels, but Hawks insists and gets his way!.

Soon the two men are on their way to Egypt to obtain all the necessary permits and scout locations. They crisscross the country for 2800 miles to check and select potential sites for filming, from the pyramids of Gizeh to Saqqara, from Luxor to Aswan….with a director diplomatically described as “never complaining, tireless, often silent and inscrutable.”

Meanwhile, Trauner has designed the sets before he ever saw a page of the script, commenting to Howard when he showed him the plans, “With all this, they can write what they like. We’re ready.” In fact, the script is far from ready. To discuss ideas Hawks has summoned his team and the writers to…St Moritz in Switzerland where he has retreated for a ski vacation with his wife Dee and their miniature poodle! Little progress is achieved and in the end, Faulkner’s contribution to the whole screenplay, besides a lot of drinking (and his obsessive quest to secure some of the 124 bottles of a Chassagne-Montrachet 1949 from a restaurant) will end up being one single sentence! Part of a scene where the Pharaoh, after work has been going on for several years on the building of the pyramid, pays a visit to his chief architect and asks: “So… how is the job getting along?”

Hollywood on the Nile: Joan Collins strikes a pose, Howard Hawks in action and working with some of the 10,000 Egyptian extras.

hulton archives/ernst haas/getty images

Howard explains how he and Trauner used 600 workers for three weeks to excavate and dress the foundations of the actual unfinished pyramid of Zawyet el Aryan. With its 100 meters descending corridor, it will serve as an impressive and authentic backdrop to show how the structure is started. Finally one day, principal photography can start. For the first shot, only a few seconds will be used on-screen, a thousand extras are required. The night before Howard doesn’t sleep much at the prospect of the challenge to choreograph such a sequence. To set the rhythm and help the men walk in cadence and unison, he has the idea of having the voice of a singer amplified through a microphone as they slowly start to drag along enormous blocks of fake rock mounted on wooden sleds…After three lengthy rehearsals, they are all bored. To stimulate them, Howard improvised and make them chant words they can’t understand like “Smoke Chesterfield”, “Drink Coca-Cola” and, after running out of slogans, he goes for a “Fuck Warner Bros”, as a dusty faced Howard Hawks watched impassively, before climbing on his Jeep to go back to the Mena House hotel by the pyramids for his daily round of golf before the ritual of the cocktail hour at the bar.

But there will be other sequences the director intends to be even more spectacular. Like an impressive panning shot encompassing a huge quarry filled with 10000 extras. Most of the soldiers from the Egyptian army, graciously offered by the government of President Neguib. 14 hours will be necessary to get the requisite take before the footage is sent to Jack Warner in California for review. “This is more precious than gold, even platinum,” Hawks remarks to Howard at the sight of the metal container with the undeveloped film…

Filming is well underway before the casting is completed and Hawks finally chooses British actor Jack Hawkins to play the Pharaoh. For the conniving and seductress captive who becomes his second wife, he asks to test Ivy Nicholson, one of the models of the moment who is flown into Cairo, but in the end, an unknown, Joan Collins, is selected. And Howard’s buddy Sydney Chaplin will play Treneh, captain of the guards. He will spend his entire salary on a brand new Ferrari.

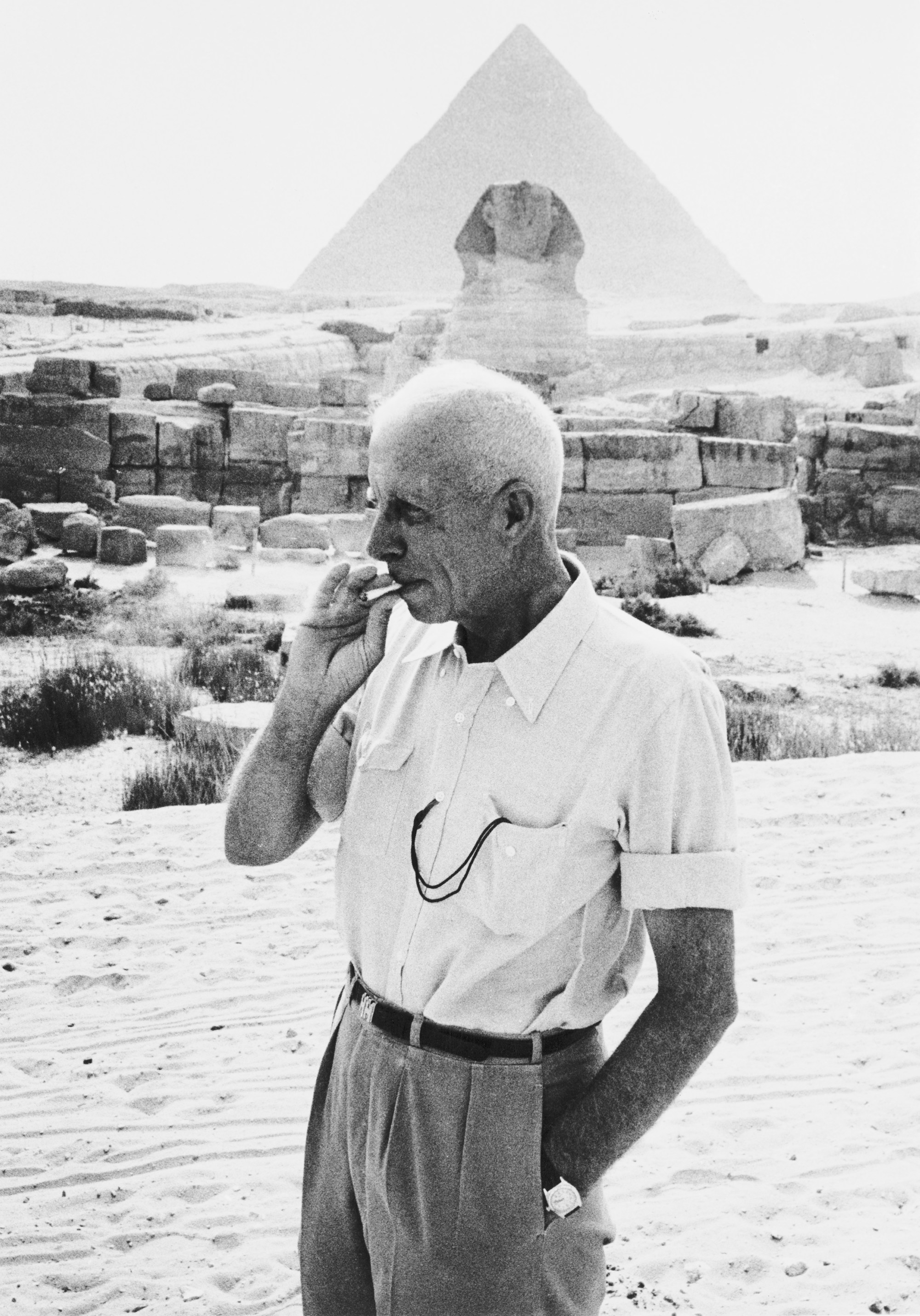

Noel Howard also mentions how several emissaries from Paramount have come to visit the set, taking copious notes. These men are spies sent by Cecil B. deMille who is preparing The Ten Commandments for the studio and wants to know what its competition is up too. In the end, Howard Hawks, then 58, remains an enigmatic Sphinx-like presence. A man of a few words who doesn’t seem to communicate much. Always impeccably dressed in bespoke safari attire (three days of fittings were necessary to complete the ideal wardrobe of director-on-location!), and Hermes custom-made ankle boots.

After four months in Egypt, the crew moves to Rome where the interiors of the movie will be filmed. “My head was too filled with sand, unreality, injustice, incomprehension, and inability,” writes a slightly nostalgic and frustrated Howard while professing his attachment to the country and its people whom he has grown to know and appreciate.

He also shares the poignant moment on May 25th, 1954, when, after another long day on the set and as he only looks forward to a gin and tonic or two to decompress, he is given a telegram informing him of the death of his longtime friend Robert Capa. He was supposed to join him in Rome to take photographs on set but stepping on a landmine in Indochina decided otherwise. On a lighter note, there is the quite surreal offer from John Huston who asks him to work on Moby Dick and if it is possible to paint a whale…white! Consulting with Faulkner for advice, the writer has a priceless laconic response: “At your age, young man, you should be able to decide for yourself if you want to build a plaster pyramid or harpoon a rubber cetacean!”

At the release on June 24, 1955, the movie is considered a flop. A far from grateful Egypt banned it because according to the censorship board of the new Nasser regime, the actor playing the architect of the pyramid, the very distinguished James Robertson Justice, a personal friend of the British Royal family, looked too Jewish! Years later, Howard Hawks himself will prevent Land of the Pharaohs from being screened during a retrospective of his films. Three years will pass until he returned to directing with Rio Bravo. As for William Faulkner, he went back to Mississippi and never wrote for the movies again. Noel Howard would continue to work as a second unit director on some prestigious productions like Love In the Afternoon, King of Kings, 55 Days at Peking, and Lawrence of Arabia…. He died in Los Angeles in February 1987.

And the Nile? Well, it still flows, as it has never ceased to do for thousands of years.