- Industry

Forgotten Hollywood: Confidential Magazine

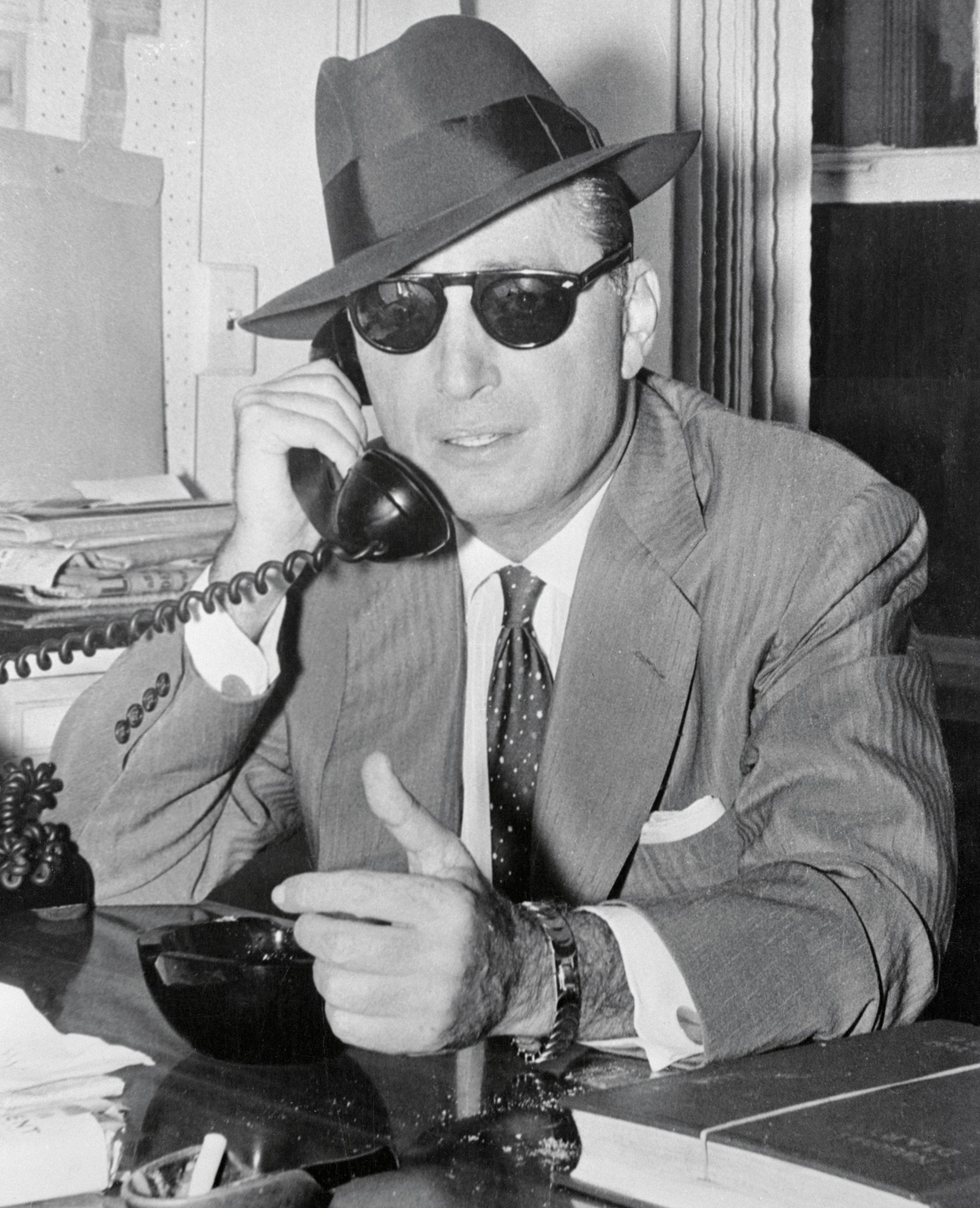

In 1957, the State of California filed suit against the Confidential magazine. Its publisher, Robert Harrison (in his New York office in the photo), made a statement in the September issue, which read in part – “California has accused us of a crime –the crime of telling the truth! ( . . . ) From Fatty Arbuckle to Bergman-Rossellini, Hollywood has had trouble with its “spoiled darlings” who have decided that the rules for “ordinary” mortals don’t apply to them. Some of these spoiled people became Communists to show how big, bad, bold and unconventional they are, others have flaunted their sexual depravity. All we have done is “blow the whistle” on a few of these spoiled ones. We have given the truth to our readers who have wanted and were entitled to the truth And for this, Hollywood wants to “get” CONFIDENTIAL. We know that an American jury will decide in our favor.”

In the 1950s, the movie studios’ grip on their stars had loosened. The contract system was collapsing and the studios’ “fixers” no longer had the power to cover up bad behavior, force gay actors into lavender marriages, prevent their interracial dating, arrange secret abortions, and bribe judges and cops to look the other way when crimes were committed. With the rise of television, fewer people were going to the movies. The Red Scare communist witch-hunts were still underway. That is when Confidential magazine hit its stride, with a circulation of 4.6 million subscribers, more than that of TIME magazine. Humphrey Bogart is reported to have said of Confidential: “Everybody reads it, but they say the cook brought it into the house.”

Harrison had hit upon a winning formula for his rag. While living a playboy life in New York City (he refused to move to LA), he established the Hollywood Research Institute (HRI), an office in Los Angeles run by his niece Marjorie and her husband Fred Meade. HRI paid informants to bring them stories about the stars. These informants signed sworn affidavits. The affidavits were then sent off to the New York lawyers for vetting and then turned into articles for the magazine. Some details were always held back as leverage in case the paper was sued. TIME defined it as “a cheesecake of innuendo, detraction, and plain smut . . . dig up one sensational ‘fact,’ embroider it for 1,500 to 2,000 words. If the subject thinks of suing, he may quickly realize that the fact is true, even if the embroidery is not.”

In the book “Confidential, Confidential, The Inside Story of Hollywood’s Notorious Scandal Magazine” by University of Buffalo law professor, Samantha Barbas, she gives some examples.

“It’s January 1955 cover story, ‘Does Desi Really Love Lucy?’ revealed Desi’s (Arnaz) flings with prostitutes. ‘Desi is certainly a duck-out daddy,’ wrote Confidential. He “sprinkled his affections all over Hollywood for a number of years. And quite a bit of it has been bestowed on vice dollies who were paid handsomely for loving Desi briefly, but presumably as effectively as Lucy. Confidential’s next issue featured a sensational story about a torrid interracial liaison between Sammy Davis Jr. and Ava Gardner, who was then married to Frank Sinatra. Some girls go for gold, but it’s bronze that ‘sends’ sultry Ava Gardner, Confidential reported. “Bob Hope slept with a floozy, according to Confidential. Errol Flynn installed a two-way mirror in his mansion that he used to spy on visitors having sex in the guest bedroom. Ava Gardner and Lana Turner took part in a rollicking threesome with a Palm Springs bartender. Eddie Fisher entertained “three chippies” in a hotel room. Kim Novak slept her way to stardom. Mike Todd cheated on his wife, Elizabeth Taylor, with a stripper; Liz cheated on Mike with actor Victor Mature. Frank Sinatra was the “Tarzan of the boudoir” because of the bowls of Wheaties he ate between rounds of lovemaking.”

The first issue of Confidential hit the stands in December 1952 after Harrison had to fold his previous 6 girlie magazines because they were not making money. He thought exposing celebrities’ private lives was a better bet. The first issue was not a success. However, Harrison hit upon a way to increase circulation with his second issue. A controversy in the news set him on the path involving Black actress Josephine Baker. Baker had gone to dinner at the Stork Club in New York where she alleged that she was not served though her white companions were. She also complained that gossip columnist and television personality, Walter Winchell, who was sitting close by, didn’t stand up for her. Winchell then defended the restaurant and criticized Baker in his column, suggesting she was a communist. Confidential picked up the story taking Winchell’s side and calling Baker “an outright liar,” Winchell waved a copy of it on his television program, and sales went through the roof. After that, Harrison made it a point to feature a story in every issue about an enemy of Winchell’s. Harrison is reported to have said, “It got to the point where some days we would sit down and rack our brains trying to think of somebody else Winchell didn’t like. We were running out of people, for Christ’s sake!”

The magazine was printed with bright red and yellow covers every two months and sold for a quarter. It had an intimate writing style, sensational headlines and alliterative descriptions like ‘tawny temptresses,’ ‘pinko partisans’ and ‘lisping lads.’ HRI’s informants included prostitutes (male and female), restaurant and hotel staff, snitches in law enforcement and doctors’ offices, bit players in Hollywood who had entrée and needed cash. The Meades scoured through public birth, death, criminal and property records. They hired detectives to tail their quarries hoping to uncover secret assignations. According to Barbas, “if a tail couldn’t get close enough to a house to find out when a car left, he’d put a Mickey Mouse watch under the back wheel. When the car pulled out, it would crush the watch, recording the time.”

Confidential also went after suspected communists in Hollywood, sensational trials of the rich and famous even if they weren’t movie stars, and published stories of abortion pills and male potency products. According to Professor Douglas O. Linder writing on famous-trials.com, a few celebrities decided to sue the magazine and hired attorney Jerry Giesler to represent them. Lisabeth Scott sued for $2.5 because she was labeled a lesbian, Robert Mitchum sued for $1 million for a story that described his behavior at a party, and Doris Duke sued for $3 million because she was accused of having an affair with a Black employee.

State Attorney General Edmund Brown (Governor Jerry Brown’s father) started an investigation against the magazine urged on by the movie studios. A grand jury was seated, testimony was taken from witnesses like Maureen O’Hara, June Allyson, Mae West, Walter Pidgeon, Liberace, and an ex-employee of the magazine, Howard Rushmore, whose main beat had been to out suspected communists. Linder writes: “On May 15, 1957, the grand jury returned indictments on charges of conspiracy to publish criminal libel, conspiracy to publish obscene material, and conspiracy to disseminate information in violation of California’s business code . . . Eleven individuals and three companies, including Confidential and Hollywood Research (the magazine’s California research arm) were indicted. The A.G.’s Office promised prison terms for violators.” But only Marjorie and Fred Meade went on trial as Harrison was a New York resident and could not be extradited under the prevailing state libel laws.

Harrison fought back by subpoenaing 177 movie stars. At once there was a stampede to leave the state by most of them. Continues Linder: “Some stars, such as Lana Turner, were caught with subpoenas on their way out of town–Turner at the Los Angeles Airport. Others tried valiantly, but unsuccessfully, to escape service, such as Dan Daily who, during his performance at the Hollywood Bowl, leaped from the stage into the audience after he spotted a process service lurking in the wings. Others had better luck: Frank Sinatra sailed his yacht into international waters, while Clark Gable enjoyed a long vacation on a Spanish beach.”

The studios panicked and tried to settle, but the zealous judge on the bench, Judge Herbert V. Walker proclaimed, “They’ll come to court even if I have to send officers with handcuffs to get them!” He refused to accept a settlement. The trial started, narrowed down to six stories that ran in Confidential. One was about Maureen O’Hara “cuddling” with her “south-of-the-border sweetie” in Row 35 of Grauman’s Chinese Theater, “heating up the back of the theater as though it were mid-January.” Another was entitled “Only the Birds and the Bees Saw What Dorothy Dandridge Did in the Woods,” accusing her of having a white lover. “Robert Mitchum . . . The Nude Who Came to Dinner” was the third, in which Mitchum was accused of stripping at a party, slathering himself with ketchup, and offering his body to any taker. (According to one report, the ketchup was only on one particular part of his body.) The other three were about Gary Cooper, June Allyson, and Mae West.

As described by Linder, Rushmore testified bitterly against Harrison with information about the informants that HRI hired. Another witness, a prostitute, spoke about setting up Desi Arnaz in a hotel room for $1,500. Yet another accused Marjorie Meade of offering to kill a story for $500. “Meade responded to Gregory’s charge of blackmail by fainting — and guaranteeing the incident headlines across the country.” One witness drowned in his bathtub soon before his testimony and another died of a drug overdose.

The jury was out for two weeks and was unable to reach a verdict. A mistrial was declared and the prosecutors vowed to retry the case. But Harrison didn’t have the stomach for a second trial and agreed to a settlement. In exchange for dropping all charges, Harrison paid a small fine of $10,000 and agreed to stop writing about the stars. But the magazine had thrived only because readers devoured salacious gossip. When that stopped, they stopped reading it. Thus ended Confidential’s reign of terror in Hollywood.

In 1990, crime novelist James Ellroy wrote “L.A .Confidential,” the third in his trilogy of neo-noir stories about Hollywood in the 1940s and ’50s. This one was about corrupt LAPD cops – the title refers to Confidential magazine. (The story has a similar magazine called Hush-Hush.) The book was made into the Curtis Hanson-directed film with the same name which garnered five Golden Globe nominations in 1997, starring Kevin Spacey, Russell Crowe, Guy Pearce, and Kim Basinger.