- Industry

Forgotten Hollywood: The Hollywood Hotel

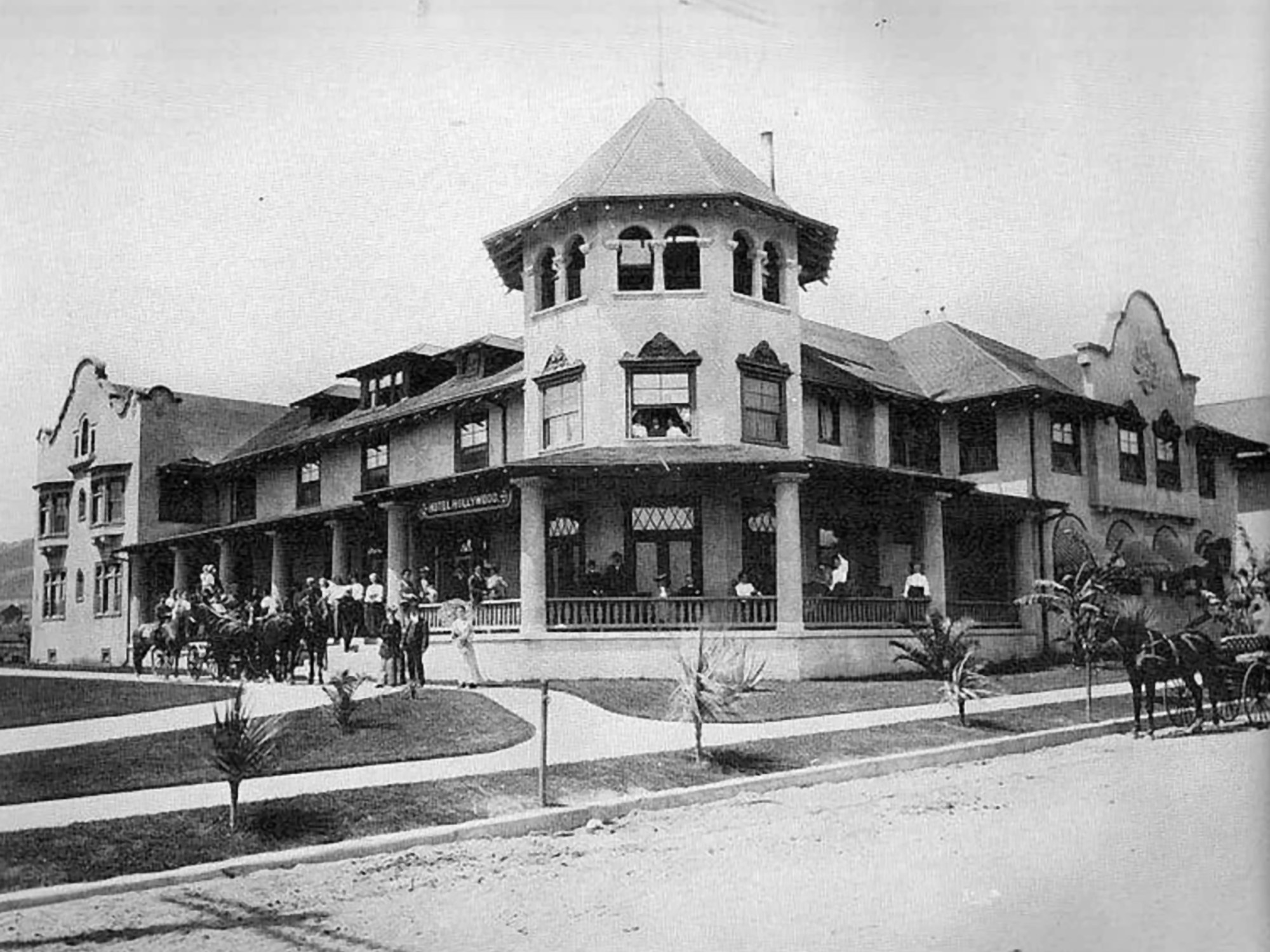

At the northwest corner of Hollywood and Highland Boulevards stands a behemoth commonplace strip mall through which movie stars walk to access the Dolby Theater, home of the Oscars. But over a hundred and twenty years ago, on that location on Prospect Avenue, as Hollywood Boulevard was then known, was the Hotel Hollywood, a gracious building erected in December 1902 by the “Father of Hollywood,” real estate developer H.J. Whitley. (The name would be changed to the Hollywood Hotel in 1910.) The famous “Balloon Route” of the Los Angeles Pacific Railroad would drop guests off at its front door.

Prospect Avenue at the turn of the century was a quiet country road in the middle of lemon orchards and vegetable fields, populated by the occasional deer and flights of quail and doves. Once the area was zoned for business, the Bank of Hollywood was set up on the northeast corner of Prospect and Highland in 1901, with George W. Hoover, a business partner of Whitley’s, as its president.

Whitley had bought 480 acres of land and contracted Hoover to build his hotel. His purpose was to establish a residential area north of Prospect called the Ocean View Tract, along with a business neighborhood around the intersection of Prospect and Highland, and sell the parcels of land. He set about attracting the pioneers of the fledgling film industry to his town. The move West made sense – there were acres of land to build studios and the sun always shone. So Louis B. Mayer, Carl Laemmle, Harry Warner, Irving Thalberg and Jesse Lasky all came to Hollywood and moved into the Hollywood Hotel.

The hotel was built in the Mission Revival style. It was made of wood but the facades were stucco. Verandas wrapped around the structure overlooked the pepper and lemon trees that surrounded it.

“The Story of Hollywood” by Gregory Paul Williams tells of how the first wing of the hotel opened in 1903 with 33 rooms and two baths. It had its own power station and an ice plant. Whitley brought prospective home buyers to tour the area and held a banquet for them at the hotel. A hundred guests were feted on its official opening day.

According to Hadley Meares writing on KCET.org, “The hotel quickly became the country club of early Hollywood society. There were art exhibitions of still life paintings by genteel ladies, social dances with music by the Wetzel Orchestra, and banquets featuring menus of ‘fastidious taste.’ At one large banquet celebrating the 1905 expansion of the hotel, 300 guests in full evening dress sat at tables covered in jonquils, while the Venetian Ladies orchestra provided music.”

The 1905 expansion included an addition to the structure bringing the number of guest rooms to 144, and including a ballroom and chapel and a new entrance. The hotel now stretched to Orchid Avenue to the west.

The renovations so impressed lumber heiress Almira Hershey that she bought the hotel and leased it to Margaret J. Anderson, a widow with two children, who also managed the property. Anderson had expanded the hotel’s rooms to 250 by the time she left in 1911, after a falling out with Hershey. The two sued each other and the lawsuits dragged out for two years. Anderson left to open the Beverly Hills Hotel after the Rodeo Land and Water Company made her an offer to own the new hotel. After she resigned, she took a lot of the Hollywood Hotel’s staff and guests with her.

However, by 1911, 15 movie companies had moved to Hollywood and the Hollywood Hotel was still popular, especially with actors. Afternoon tea was served every day. Thursday night dances were popular, and so were the Sunday evening concerts. The hotel’s dining room served five-course meals. As a precursor to the stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, the dining room of the hotel had stars with the names of its famous guests on its ceiling, including Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, Alla Nazimova, Greta Garbo and Buster Keaton. The Thursday night dances brought out stars like Gloria Swanson, Mabel Normand, John Gilbert and Wallace Reid.

“The Story of Hollywood” recounts how the puritanical Hershey kept a strict eye on the celebrities, acting being considered a low profession at the time. She counted the courses they were served so they wouldn’t grab extra food and made sure that the actresses were alone in their rooms by tapping on their doors nightly. She monitored the ballroom and made sure the dancing didn’t get too amorous. But she couldn’t control the alcohol that guests smuggled into the hotel.

Actor Ben Lyon told the Los Angeles Times, “What a thrill it was to be living under the same roof that had housed Valentino, Thomas Meighan, Charlie Farrell, Gilbert Roland and many other great stars! However, there was one catch which we all were aware of, and that was the Thursday night dance in the lobby. The…elderly, charming and buxom… [Miss] Hershey…adored dancing to the three-piece orchestra. But she was not a Leslie Caron…we young male guests had to line up and take turns dancing her around the lobby or chance being asked to give up our rooms. Needless to say, we danced with her.”

Rudolf Valentino, the famous silent movie star, who started his career as a dancer, would dance the tango in the hotel’s ballroom. One of his partners was screenwriter June Mathis who cast him in Metro’s Four Horseman of the Apocalypse, which made him a star and led to his movie The Sheik which will forever be associated with his stardom. It was in the lobby of the Hollywood Hotel that he met his first wife, actress Jean Acker. The two married in 1919 and spent their honeymoon night there, where she locked him out of their room, Room 264. (She was a lesbian reportedly dating movie star Alla Nazimova; the marriage was never consummated and an “interlocutory” divorce was granted them only in 1922.) Apparently, hordes of tourists requested Valentino’s room, and the hotel was not slow in designating every room as his.

There is also the story of actress Mae Murray, a resident of the hotel in 1916 according to a census document, who moved into the hotel with one of her four husbands – the record is unclear about which one – on their wedding night and then was kicked down the stairs by him two hours later. She fled the hotel.

Actress Virginia Rappe also lived in the Hollywood Hotel. She was the starlet who caused the downfall of star Fatty Arbuckle when she was found raped and dead at a party they attended. It is likely that she met him at the hotel, where he was a frequent attendee of the Thursday night dances.

In 1934, powerful Hearst syndicate gossip columnist Louella Parsons started her radio show “Hollywood Hotel,” ostensibly from the hotel but actually recorded in a studio. Hers was the first radio show to originate from the West coast and was even distributed in Canada and Australia. It was a sort of variety show with songs, film gossip, an interview with a movie star and a 20-minute dramatized adaptation of an upcoming movie, the first episode featuring Claudette Colbert who was appearing in Imitation of Life. The actors were not paid to appear but received a case of soup from the program’s sponsor, Campbell’s Soup Company.

A 1937 movie musical called Hollywood Hotel was based on the radio show and starred Parsons in a small role, Warner Bros’ biggest musical star, Dick Powell, and an uncredited Ronald Reagan. It is best known for its striking number “Hooray for Hollywood,” a visual extravaganza choreographed by Busby Berkeley with dancers dressed in calla lily-covered gowns dancing through a montage of neon signs of Hollywood’s best-known landmarks – the Brown Derby, Trocadero, the Ambassador Hotel, Grauman’s Chinese Theater, and Hollywood Boulevard. Warner Bros. made the movie without getting permission to use the name and was sued by both the Campbell Soup Company and the Hollywood Hotel. Some exteriors of the hotel appear in the film.

Hershey died in 1930 and her heirs sold the hotel in 1947. By now it was seedy and run down, its residents mostly elderly, sitting on the porch in their rocking chairs. In 1956, the hotel was razed to make way for the First Federal Savings and Loan of Hollywood building, which in turn gave way to the Hollywood and Highland mall in 1998.

The hotel’s guest ledger is now in the Smithsonian.