- Film

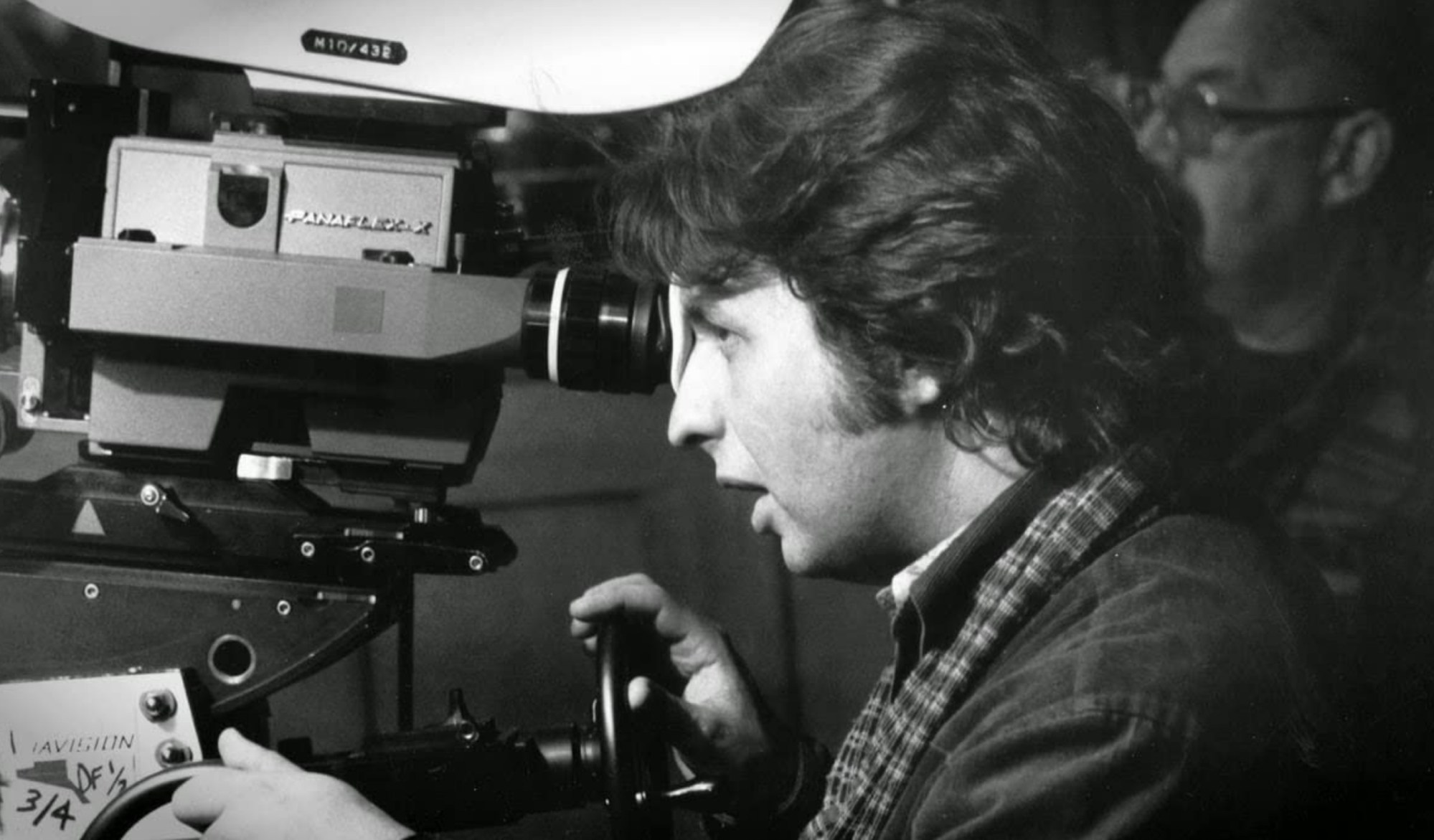

Forgotten Hollywood: The Making of Heaven’s Gate (1980)

In a radio interview, Willem Dafoe talked about being fired from his very first film. He was a ‘glorified extra’ on the set of the epic Heaven’s Gate in Montana and recalled, “One day we’re sitting in a lighting setup, eight hours, full makeup, full costume, and we’re not even going to shoot. We’re just seeing how the light is for shooting the next day. It’s a little tedious, but I’m a patient man. I’m sitting there, someone told me a joke, and I laughed. audibly. Michael Cimino, the director had his back to this group. He heard the laugh. And he just turned around and said, Willem, step out.” Dafoe was given a plane ticket home. He had lasted three months on the eight-month shoot.

In a twist of irony, Dafoe narrates the 2004 documentary Final Cut: The Making and Unmaking of Heaven’s Gate (available on YouTube) based on the 1985 book of the same name chronicling the whole disastrous production written by Steven Bach, a United Artists vice president who oversaw the entire film and was himself fired.

UA collapsed because of the runaway budget, excessive hubris of the director who was called ‘the Ayatollah’ by the crew, and the scathing reviews there was no coming back from. To this day, Heaven’s Gate is best known as the film that tanked a studio.

In 1978, Cimino’s The Deer Hunter had just been released to huge acclaim and would go on to win five Oscars, including Best Director and Best Picture. Cimino knew he could write his own ticket in Hollywood and brought his script Heaven’s Gate to the UA executives, asking for about $8 million to make it. He was given $12.5 million to have it ready for release by Christmas 1979 in time for the next Oscars. Unprecedentedly, his contract stated that despite his best efforts to make the date, if he missed it and there were cost overruns, UA would have to swallow them. Cimino also got final cut written into his contract. He would get paid $500,000 plus weekly expenses of $2,000. He wanted the picture to be presented as “Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate” with his name above the title in the same size font.

To be given final cut was not unusual at the time. The auteur theory of filmmaking had taken hold in Hollywood and directors were empowered to realize their vision with complete control. This was actually not working out so well. After the successes of the early 70s came a number of flops by auteur directors – Martin Scorsese with New York, New York, William Friedkin’s Sorcerer, Peter Bogdanovich’s At Long Last Love, and Steven Spielberg’s 1941. Nevertheless, Cimino was given complete artistic and financial control.

The script, set in the 1890s, was based on the true story of the range wars of Wyoming where European immigrants got into conflicts with local cattle barons leading to a final battle. Kris Kristofferson, who plays a local marshal, and Jeff Bridges, who owns the local saloon/hotel, side with the immigrants. Isabelle Huppert plays a prostitute who is Kristofferson’s love interest; Brad Dourif was cast as the apothecary, and Sam Waterston played the leader of the mercenary gang.

The first clash with Cimino came when he insisted on casting Huppert, despite making a deal with the executives that he wouldn’t do so if they found that her accent was not authentic. According to Bach, Cimino told them over the phone to go f*** themselves and hung up on them. (Diane Keaton and Jane Fonda, the leading actresses of the day, had already passed on the film.)

The meter started running on the production when the cast was sent to what they dubbed ‘Cimino Camp,’ extensive training in roller skating for an elaborate waltz scene (that, ironically, didn’t make the final final cut – there were many, many cuts), riding, cockfighting, and shooting. This went on for six weeks. Elaborate sets were built and rebuilt – one street set had houses on both sides of the road torn out and rebuilt because Cimino wanted more space between them and pulling down just one side just wouldn’t do. 1,200 extras were hired, and horses were auditioned. A vintage train was trucked from a Denver museum to Montana as it wouldn’t fit through railway tunnels.

Principal production began in April 1979. The two main locations were Glacier National Park and the Two Medicine area, both near Kalispell, Montana. According to Bach, Cimino was five days behind schedule after six days of shooting. He had burned through $900,000 for a minute of usable footage. After two weeks, he was ten days behind with three minutes of usable footage. Bach calculated that the film was costing a million dollars a minute.

Cimino was a perfectionist. He was making the ultimate western and would not be hurried. Every scene was obsessively planned, Cimino hand-picking the extras and positioning them himself. If it took all day to get the perfect light or cloud cover to appear, everyone would have to wait (on call, on double time, on meal penalty) till Cimino decided it had appeared. And then there were the takes, the re-takes, and the re-takes of the re-takes. He gave very little direction but made the actors redo their scenes in multiple different ways. Scenes that lasted seconds onscreen were done 50 or more times. In the documentary, Dourif said, “I’m not used to doing 57 takes, I’m really not. I’m not used to doing a minimum of 32 takes. It was like workshopping on film – we did the happy version, we did the crying version, we did the furious version.”

The final battle scene between the mercenaries and the locals was set in a location a three-hour drive away from Kalispell. It involved gunfights on horseback and from wagons, dozens of extras, and multiple explosions. Cimino had also installed a special irrigation system to make the grass grow greener, clearing out rocks and vegetation to do so. In the documentary, Dourif talks about getting into a van at 3.30 AM each morning, clutching a pillow and blanket, anxious to catch some extra sleep on the drive to the location. The battle scene alone was the length of a regular movie in Cimino’s first cut, coming in at two hours.

Bach and Field were beside themselves. They considered firing Cimino but decided they would cross their fingers and hope for an Apocalypse Now-type situation in which a masterpiece emerged from a very troubled production. They sent an experienced UA production executive, Derek Kavanaugh, to monitor and help Cimino. Furious, Cimino sent them a letter forbidding Kavanaugh to approach him, speak to him, or even set foot on the set. Finally, the producer (and Cimino’s friend) Joann Carelli was fired by UA and the executives became the producers, effectively reducing Cimino to a studio employee, holding over his head the cancelation of his right to final cut. A new production schedule was created, and the budget was capped at $25 million. Cimino agreed to the terms and sped up production.

At one point, UA also tried to sell the movie or bring in production partners to no avail.

For obvious reasons, Cimino had barred the press from the set. An enterprising freelancer, Les Gapay, decided to hire on as an extra at $30 per day for a couple of months and wrote a devastating expose about the production that was picked up like wildfire by the media. Published in the Washington Post, and subsequently syndicated all over, Gapay wrote about all the production excesses, the treatment of extras and horses, the accidents on set, and Cimino’s tunnel-visioned obsession with his self-defined perfection.

Bach summarizes Gapay’s article in his book: “Extras were fainting; their toes (including Gapay’s own) were being crushed; they were being bruised; they were forced to wallow in mud and swelter in the heat. They inhaled earth, dust, and chemical smoke. There weren’t enough bathroom facilities. They were treated rudely. On one shooting day, sixteen people were injured. On another, work began at seven-thirty in the morning, and lunch was not provided until four-thirty in the afternoon. They were shunted off with printed notices reading, “Please do not approach the actors or crew members.” They overheard an assistant director tell a wagon driver, “If people don’t move out of your way, run them over.”

“It was a tale of gory, reckless excess, illustrated with photographs by the author (since no others had been made available), and in all the economic, environmental, muddy, sweaty, bone-cracking, bladder-bursting mayhem, the enterprising “extra” noted that the biggest spender of all was Cimino, who bought not only a $10,000 jeep, “but also 156 acres of land.” (Gapay kept track of that land and noted with some amusement several years later that Cimino’s love affair with Montana had apparently cooled. In mid-1984, the land was up for sale, but there were “no takers.”)”

Gapay noted his own experience in a scene in his article: “About 120 extras wearing suits, winter coats, hats, ties, and wool dresses sat through four hours of shooting without a break in a hot crowded room filled with smoke for effect … Some extras fainted … In the week-long filming of the cockfight scene in heat and smoke, extras and actors wearing heavy clothes were given few breaks. Crew members fought off the smoke by wearing surgical masks. The birds were removed from the building between takes and periodically replaced by fresh roosters, but there was no such treatment for the humans.”

Heaven’s Gate was finally wrapped a year behind its schedule, with 1.3 million feet of footage to edit. After eight months of editing where Cimino changed the locks and barred the windows in the editing room to keep everyone out, he produced a 5½ hour cut to the fury of the executives. He was ordered to go back and recut to a more manageable (and saleable) length, in time for Christmas and the 1980 Oscar window. The next cut came in at 3 hours and 39 minutes.

Apparently, the print was still wet from editing at the premiere on November 19, 1980, so none of the executives had seen the cut that was shown.

The brutal reaction to the film by the critics had the principals reeling. Vincent Canby of the New York Times wrote that the film “fails so completely that you might suspect Mr. Cimino sold his soul to obtain the success of The Deer Hunter and the Devil has just come around to collect.” That was just one of the withering reviews.

UA pulled the film out of cinemas a week later. Cimino wrote an open letter in the trades asking to be allowed to recut the film some more. That was approved, then canceled, but a final version appeared in April 1981 that was no better received.

All in all, Heaven’s Gate cost UA $44 million. UA was sold to MGM. And the era of director-driven films was over as studios took back control of productions.

After the perspective of a few years, Heaven’s Gate was reassessed with more favorable reviews. It was generally held that critics were reviewing the bad press the production received instead of the movie itself. Fans of the movie include Martin Scorsese.